This article originally appeared in the March/April 2013 edition of Museum magazine.

An excerpt from Exhibitions · Concept Planning and Design, The AAM Press, 2012.

Museum objects are like words-they make sense only when they are organized to convey a message. Thus, comprehension of the exhibition concept is imperative to begin the design process. The quest for an outstanding and meaningful exhibition is realized when good design, a needs and resources analysis, and conceptual development come together with thought and understanding. Then the nature of the installation becomes obvious. The presentation reveals a quality of convincing continuity and simplicity regardless of the diversity and number of pieces in the exhibition. This occurs precisely because the cohesive interaction of these three aspects of exhibit planning determines what needs to be included and how the exhibition should be organized.

The environment that surrounds objects and works of art influences the ways in which we see them. It confers meaning. The background or setting of an exhibition can suggest a synergy compatible with the works or it can create a tension that either heightens the impact or conversely serves to cancel the conceptual integrity and meaning. For example, changing a space’s proportions, color, value or lighting affects the way people feel in the space. The issue becomes, is the presentation consistent with the conceptual context of the exhibition? The intricacies of context inevitably influence human perception and give significance to the objects. Thus, good design depends on an articulation and understanding of the exhibition’s concept.

Also, a strong, well-planned interpretive framework that gives viewers the opportunity to construct meaning that extends beyond pure aesthetics is integral to a good exhibition. Ideally, the manner in which objects are displayed should communicate their visual power and their significance in the society that made and used them. Above that, the presentation and interpretation should enable the viewer to perceive the expressive potential of objects and the ideas they embody in new ways that address personal and societal concerns. The installation design should assist in conveying this information and the overall purpose of the exhibition to visitors. Just as care is given to how exhibitions are intended to be understood, regard for how they may be misinterpreted must be anticipated.

To begin, a well-formulated conceptual framework for the exhibition is essential. Often, it is termed the big idea; a theme that allows visitors to comprehend a particular subject. It enables visitors to feel there is a certain order (a beginning, middle and end) that guides their experience. The big idea establishes the meaning and intention of the exhibition and provides the rationale for everything that is included. Working deductively from the whole to the parts; by first defining the most global objectives of the exhibition and progressively establishing the manner in which those goals will be realized through the objects-gives coherence to the parts and the whole. Conceptual structure and familiarity with the objects most often convey a thematic feeling-a mood-that suggests the general character of the installation.

Exploration/Discovery

Exhibit development is a complex, nuanced process that integrates scholarship with goals of audience engagement. It usually starts with the curator, but sometimes an exhibit team includes education specialists, the designer and others who work together to define the concept and refine meaning.

Curators approach an exhibition from the perspective of content. Their familiarity with and knowledge of the subject and the material to be included in the exhibition are important to establishment of the big idea and to the scholarly veracity of the interpretation.

Educators are the team members most often involved in the multifaceted aspects of museum interpretation and, thus, are more likely to bring considerations of the audience into the planning of an exhibition. They generally are the first to ask questions about the impact of a particular decision on visitors.

Designers provide structure for the messages and meanings inherent in the exhibition. Their concerns for aesthetics, space, accessibility, and costs are closely allied to communication. They, like the educator, take on the role of audience advocacy. Their visual and spatial literacy, coupled with verbal fluency and an ability to synthesize information, determines how visitors will experience an exhibition.

The team approach in which curators, educators, and designers work together has certain advantages in bringing multiple skills and approaches of thinking to exhibition planning. Usually, this results in a wider range of ideas, a better comprehension of others’ jobs and an empathetic working relationship. Nevertheless, depending on the makeup of the team and its ability to work together, the team process can hinder innovation and efficiency. The team approach demands a democratic interaction in which all members of the team feel free to advocate for their areas of concern without fear of alienating others.

Optimally, when the journey entails exploration and discovery, an unanticipated conclusion is reached. Through this method, the curator and those working on the exhibition and, subsequently, the viewers, will gain new insights and make discoveries that are more engaging and certainly more interesting to experience. Connections will be articulated that, at first, could not be imagined. In the end, the exhibition will be more than the sum of its parts. The exhibition organizers will have gone over the edge, into the unknown, and created something new; and they will have provided new insight.

By using this method, in the beginning, the curator does not know precisely the evolving direction of the big idea; especially what the conclusions will be. This approach to exhibition organization runs counter to the usual rationale of making an outline. While outlines have their function, they only provide a way to organize ideas and present them in an orderly way. Order supplants and intercepts inspiration because the skeleton of the structured outline is filled in. Hence, the ability to provide creative expression for the exhibition is stifled and the exhibition itself often will be boring.

The exploration/ discovery method fosters creativity in the maturation process and produces an exhibition that is almost always more interesting to experience. It is active, whereas the outline orientation to an exhibition, no matter how right it might seem, is static.

An Inquirer’s Stance

To develop the focus of an exhibition, organizers need to assume an inquirer’s stance, asking themselves questions about the topic: What is the message to be conveyed? What is the purpose? Who? What? When? Where? Also, ask how/why questions that go beyond fact into inquiry. Why is the topic relevant or interesting today? How does it fit into current scholarship on the topic? What impact do I want to make? Then ask: Who is the audience? What do they already know and what do they expect to learn?

An efficient strategy for creating questions from a topic is to set forth a one-sentence statement that becomes the big idea and guides the planning. State the topic, formulate a research question and provide a rationale for the research, i.e., I am researching topic to find out research question to understand rationale/significance.

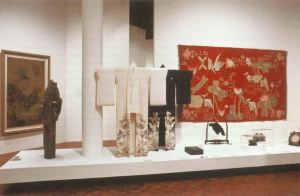

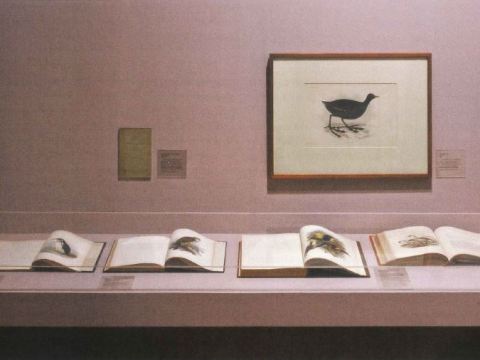

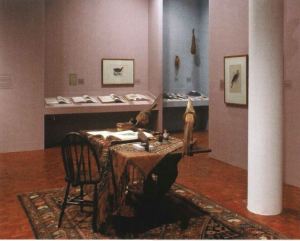

For example, the statement for the University of Hawaii Art Gallery’s 1994 exhibit, “On Heavenly Wings: Birds and Aspirations,” was: “I am researching birds (topic) to find out how birds have influenced our lives (research question) to understand the interconnection of our world (rationale/significance) .” From that sentence, a framework was created that showed how vastly different cultures, artists, and scholars of diverse disciplines are inspired and derive meaning from birds and flight.

Articulating the premise of the exhibition in this simple and forthright manner serves to keep the research focused, but, most importantly, it pushes beyond only presenting things. This approach forces the curator or exhibit team to analyze the significance of the available objects in relation to the theme of the exhibition. Besides delineating what will and will not be included in the exhibition, it aids in the development of a coherent story-line that uses the artifacts to tell the story instead of the message being a construct about the artifacts themselves. Importantly, the objects become the means, not the end. The artifacts serve as powerful tools to enable the objective of the exhibition to be communicated with clarity. The overriding mission is to help people leave the exhibition feeling different from when they came in. For visitors, an exhibition succeeds when the research strategy surrounding the big idea comes through; when the topic makes sense, the research question matters and the rationale/significance inspires.

An effective method of organizing thoughts is brainstorming. Talk with colleagues about the topic. Make a random list of topics, subjects, and ideas that could be addressed in the exhibition. Ask others to suggest resources: books and other experts. Do related reading. Use the library, periodicals, Internet. Keep collecting information, but analyze its potential for use. Is it relevant to your focus? Keep searching for the most pertinent sources and for alternate views. Critically evaluate the data you are gathering. Does the author take a scientific or cultural approach or some other perspective? Keep adding to your list and, as you do, certain patterns will emerge. Cluster these ideas and fill out the list in greater detail, constantly grouping things as you go along. Many ideas will eventually be discarded. New ideas and modifications will occur. Some of these will help to tie things together; to serve as transitions, but keep returning to the essence of the exhibition contained in your one-sentence statement. In the process, depending on the objects and the information discovered in the research, a flexible outline transpires. The conclusion may be very different from what was originally imagined, but this is the manner of creative research.

Creativity manifests itself most powerfully throughout the project planning, from a continuous alternation between focusing on the whole and on the parts. Through this strategy, we move back and forth between the definition, and possible redefinition, of the exhibition objectives and the choice of objects with their capacity to contribute to an understanding of the overriding concept. This procedure balances rationality (working deductively) with playfulness, allowing the discovery of potentialities within the subject that were not evident at first. Sometimes seemingly trivial ideas may surface. They should not be discarded immediately, as many could add richness to the conclusion.

The written statement that expresses the big idea is used by the exhibit team and rarely serves as a label or introductory statement for visitors. However, it guides the development and interpretation and increases the potential for visitors, in their own way, to decipher the exhibition’s objectives. Often it allows them to see multiple viewpoints and to reach their own conclusions.

Conceptual problems generally can be traced to the scholarship guiding the content. Although viewers are drawn to artifacts and objects, selection and interpretation must be relevant to the exhibition’s focus as visitors need to connect to the objects within a larger social context so meaning is discerned. While exhibitions demand that planners become immersed in the minutiae of their material, this immersion should not lose sight of substantive conceptual issues.

A careful analytical balance must be established between the visitors’ desires to identify with concrete things or people as opposed to abstract ideas. Exhibition objectives generally fall into two categories: the concrete and specific, or abstract and broad. An example of the concrete/specific would be an exhibition on how to identify birds by the colors of their plumage and their calls. “On Heavenly Wings: Birds and Aspirations” constituted an exhibition with abstract objectives (“how birds have influenced our lives to understand the interconnection of our world”) that had as its basis cultural and ecological concerns. Exhibitions that are concrete and specific are easier to develop. There is an evident logic to their organization and generally, they are easy to understand. Abstract and broad exhibition objectives, however, present greater challenges for the planners in that they demand careful thought of how important, more universal, ideas are communicated to the audience in ways that are engaging.

An analysis of how the material to be presented can best be understood by visitors-and of how the installation design can enhance the intended visitor response is integral to a conceptual approach to planning and design. Exhibitions, after all, are addressed to the visitors. The goal is to make the art or the collection accessible to viewers. It must encourage visitors to gather, from their experience, a greater understanding of and appreciation for what they are seeing.

Hello Tom,

Do you have an example of a content outline for museum exhibitions?