This exhibition critique first appeared in the journal Exhibition (Spring 2025) Vol. 44 No. 1 and is reproduced with permission.

Exhibition information:

Belle da Costa Greene: A Librarian’s Legacy

Morgan Library & Museum, New York, New York

October 25, 2024–May 4, 2025

Website: https://www.themorgan.org/exhibitions/belle-da-costa-greene

In 1948 the Morgan Library & Museum celebrated Belle da Costa Greene, its first director, with an exhibition showcasing rare manuscripts, drawings, and books she had added to the library. Seventy-six years later, the institute honors Greene again.

Belle da Costa Greene was a transformative librarian: she was a book agent, curator, and institutional director when these positions were almost always occupied by men. By her death in 1950, the librarian whom J. Pierpont Morgan once dubbed “the cleverest girl I know” had become a legend in the art and book worlds.

Recognitions of Greene’s achievements furnish a story of their own. She was one of the first women elected a Fellow of the Medieval Academy of America. She was named a permanent fellow by the Metropolitan Museum, served on the advisory board of the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore and on the editorial boards of the Gazette des Beaux Arts and ARTnews, and was awarded Les Palmes d’Officier de l’Instruction Publique by France for her service to education.

And yet, even grand reputations often diminish after death. Subsequent commemorations within the Morgan Library were scarce and perfunctory.[1] Morgan’s biographer Jean Strouse put Belle Greene back on the cultural agenda when she revealed that Greene was the daughter of Richard T. Greener, an educator, diplomat, and activist, who was also the first Black man to graduate from Harvard University, and Genevieve Ida Fleet (fig. 1). Greene had passed successfully all her working life. Strouse’s revelation reoriented views of Morgan’s librarian dramatically. She also gave the librarian a voice, including numerous citations from Greene’s letters to American connoisseur Bernard Berenson in her biography. In one swoop, Greene became notable for being a Black woman passing as white as much as for her work as a librarian. Two subsequent books, Heidi Ardizzone’s biography, An Illuminated Life: Belle da Costa Greene’s Journey from Prejudice to Privilege (2007) and Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray’s fictional biography, The Personal Librarian (2021), further amplified Strouse’s discovery.

With Belle da Costa Greene: A Librarian’s Legacy, the Morgan Library & Museum celebrates Greene as nothing less than “the most fascinating librarian in American history.”[2] The show pays tribute to the two Belles—Belle Marion Greener, born into an elite Black neighborhood in Washington, DC, and Belle da Costa Greene, Morgan’s pathbreaking personal librarian.

As visitors enter the exhibition, they find themselves before a photograph of a smiling Belle Greene (fig. 2). Facing us directly, she seems to welcome us into the show. Elegant books frame the photograph. Above her portrait are Greene’s own words: “I knew definitely by the time I was twelve years old that I wanted to work with rare books. I loved them even then, the sight of them, the romance of them” (fig. 3).[3] Thus begins this multivalent exhibition of a multifaceted woman.

The first of two galleries explores the Greener family’s beginnings in Washington, DC, Belle’s early education, passing, her work at Princeton, and her first years working for Morgan. Visitors move from Black spaces (Belle Greene’s Washington) to a diverse space (the Northfield Seminary for Young Ladies) to white enclaves (Princeton, Morgan’s private library). This section opens with Adolph Sachse’s National Capital, Washington, DC, a striking period drawing to which the exhibition’s creators have added information on the city’s Black residential areas (fig.4). Among the highlights of this section are documents illustrating Fleet’s music teaching and Greener’s bibliophilic interests: it is clear that both parents influenced their daughter’s later cultural pursuits.

The exhibition’s second section, An Empowering Education, includes the first known photograph of Greene (fig. 5). Two letters from 1896, one written by Belle and one by her mother, suggest identities in transition. Neither Fleet nor her daughter render the final “r” of Greener clearly. Here Belle seems to flicker between two identities—Belle Greener and Belle Greene.

Questioning the Color Line, the largest section of the first gallery, includes artistic depictions of passing alongside historical documents showing the risks against which passing took place. A wall quote from Nella Larsen’s 1929 novel Passing underscores the contradictions which passing arouses: “It’s funny about ‘passing.’ We disapprove of it and at the same time condone it. It excites our contempt and yet we admire it. We shy away from it with an odd kind of revulsion, but we protect it” (fig.6).

Film clips from African American director Oscar Micheaux’s Veiled Aristocrats (1932) and John M. Stahl’s Imitation of Life (1934) feature painful scenes between white-passing characters and their family members. The presentation places Greene in a melodramatic and conventional story about passing that stresses self-division and angst. The contextual objects and wall texts do not clarify Greene’s particular relationship to passing, which was of a significantly different order and done without estrangement from her family. There is nothing in this section that explains how different Greene’s life was from others who crossed the color line.

Visitors find themselves in a quandary: Greene appears as a Black woman in some photos, yet the object labels do not address her silence on her experience of passing. Many will wonder about the relationship of these images to one another. This section presents possibilities and alternatives, such as the anguished scenes shown in the film clips, but we do not know, and perhaps can never know, whether Greene had similar moments of self-doubt and inauthenticity.

Many visitors will wonder, too, if J. Pierpont or his son Jack Morgan knew anything about Greene’s ancestry. Again, there is no clear answer to this question. “If Morgan knew about Belle’s background,” observes Strouse, “he left no indication of it. Once she became indispensable at his library, he might not have cared.”[4] One might approach Greene’s experience less in terms of melodrama and conventions developed in film and popular culture and more in terms of the power of Morgan’s wealth to control the narrative about his librarian. Passing, as Greene did, under the protection of great wealth and power, made her situation unique.

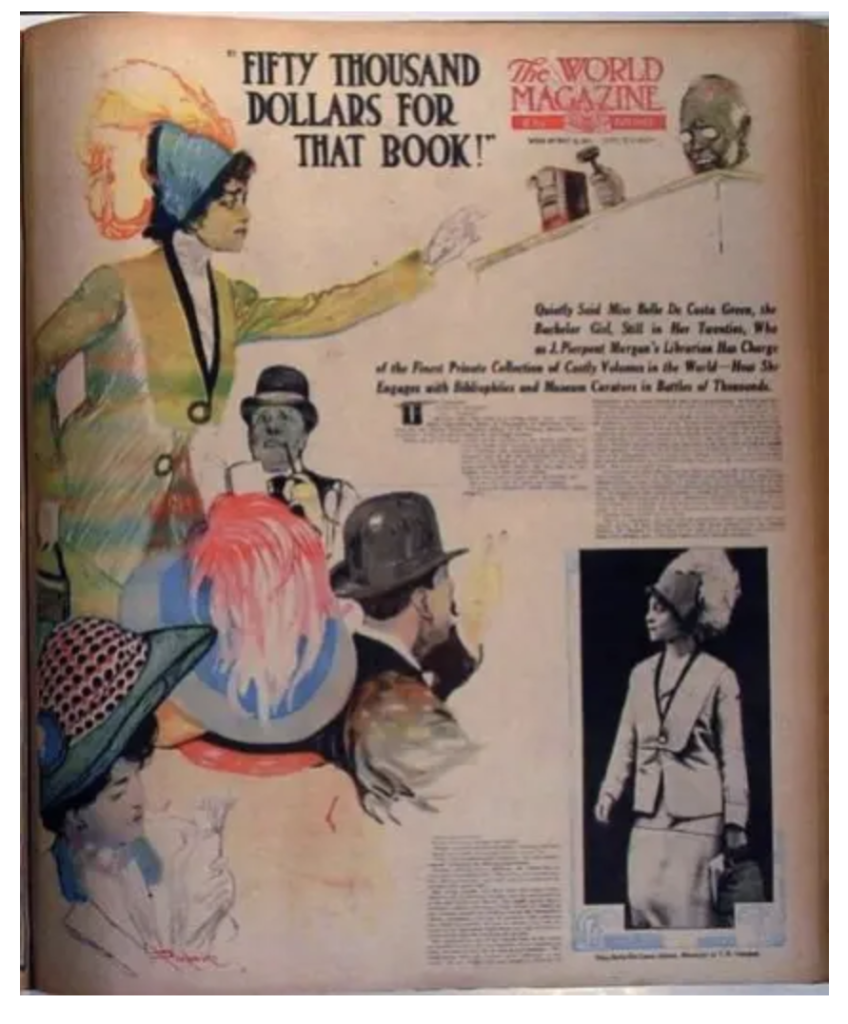

The final sections of the first gallery—Working for the Morgans and First Acquisitions—transport us to Morgan’s resplendent library. Examples of Greene’s stunning early acquisitions, notably two books printed by William Caxton, the first printer of books in England, are displayed alongside a newspaper article. Greene’s acquisition of Caxton’s Le Morte d’Arthur at an auction with a bid of $42,800 transformed her into a celebrity (fig. 7). Following this coup, newspapers across the country began running stories on the librarian who had gained Morgan’s trust.

Embedded in this section are photographs and letters depicting Greene’s relationship with another prominent figure, American art historian Bernard Berenson. Excluding family members and Morgan himself, Berenson was the most important person in Greene’s life for many years and the love of her life. The photographs and letters offer but a glimpse of the centrality of this relationship.

Of the roughly 600 letters she wrote to the connoisseur, only two are displayed, one an early note to “Mr. Berenson,” the other a letter describing her loneliness after Morgan’s death. Neither exhibit the intensity of this romance, much less Greene’s vibrant character. Berenson described Greene as “incredibly and miraculously responsive.”[5] Her letters brim with effervescent descriptions of her responses to books and art. The portrait of Greene that emerges in this exhibition, however, tempers this exuberance.

Discerning visitors can glean some sense of Berenson’s centrality from the many wall quotes and labels taken from the librarian’s letters to him. Long held at I Tatti: The Harvard Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, the letters are now available online.[6] This digital archive, a partnership between the Morgan and I Tatti, enhances the offerings of the exhibition.

The last object in this first gallery is a chalk drawing of Greene by Paul-César Helleu, which furnishes one of the most striking images of the librarian (fig. 8). Greene once described the drawing as “1% of Belle Greene, 99 of Paul Helleu.” Showcasing her poise and beauty, the drawing celebrates Morgan’s librarian as the embodiment of a glamorous modern woman. As the last object in the first gallery, it anticipates well the next phase of Greene’s storied career.

The second gallery highlights the librarian’s acquisitions, her workplace, and her accomplishments. The grand objects of a grand life include elegant furnishings from her office, rare illuminated manuscripts, and Renaissance paintings. These objects spotlight “Morgan Quality,” a standard known to contemporaries as not so much good or excellent, but supreme.[7]

Items from the librarian’s personal collection—The Thousand and One Nights, Dante’s Vita Nuova, Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, leaves from Islamic manuscripts, a Durer print, and drawings by Marius de Zayas and Abraham Walkowitz—illustrate the range of her literary and artistic tastes. Modern works, some acquired from Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 avant-garde gallery, offer a glimpse of Greene’s world beyond Morgan’s library.

Two smaller sections, one on Black librarianship, the other on Greene’s nephew Robert MacKenzie Leveridge (known as Bobbie), also explore worlds beyond the library. Bobbie committed suicide during WWII after receiving a vile letter from his white fiancée that exposed his aunt’s ancestry. Racism, as the wall label makes clear, was the cause of his death. In this instance, the personal cost of passing was unbearably high.

The section on Black librarianship presents a dramatic contrast to Greene’s reality. The section highlights the lives and achievements of Regina Anderson Andrews and Catherine Latimer, two groundbreaking Black librarians employed by the New York Public Library. Coming at the end of the section on Greene’s achievements as the Morgan Library & Museum’s first director, this thematic grouping furnishes enlightening historical information, with the women’s stories functioning largely as a point of contrast. Greene’s career and successes were far removed from the noble and largely unknown public service of most Black librarians.

One of the final objects of the exhibition, a letter Greene acquired for the library written by famed abolitionist and orator Frederick Douglass to H.D. Husbands, also draws attention to race. In one passage Douglass addresses the importance of giving Black Americans opportunities to apply for government jobs. Does the purchase show Greene following the Morgan’s established program of adding to the library’s existing collection of Douglass letters? Or does the acquisition reveal a personal commitment to racial uplift? Was she thinking of her father’s work on civil rights? These are but some of the questions this exhibition will spark.

With this centenary exhibition, the Morgan Library & Museum pays splendid tribute to Belle da Costa Greene and her complex history. Few institutions have honored their librarians so lavishly. The two curators, Philip Palmer and Erica Cialella, are to be commended for assembling an homage that will stimulate meditations on race, identity, representation, motivation, and passing, while never losing sight of their subject—the fascinating and multifaceted Greene.

Deborah Parker is Professor of Italian at the University of Virginia. She is the author of Becoming Belle da Costa Greene: A Visionary Librarian Through Her Letters (2024) and coauthored “Literature and Belle da Costa Greene” with Philip S. Palmer for the Morgan Library & Museum’s catalogue, Belle da Costa Greene: A Librarian’s Legacy.

[1] In the 1960s, the Hroswitha Club, whose members were women bibliophiles and collectors, donated 16 wooden carvings of printers’ marks to the Morgan as a memorial to Greene. They were hung then later removed. Information on Greene was added to the “About” section of the menu bar of the Morgan Library & Museum website only in June 2021.

[2] “The Most Fascinating Librarian in American History: Telling the Story of Belle da Costa Greene,” Morgan Library & Museum, YouTube, video, October 19, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fin67OHO068.

[3] Belle da Costa Greene, quoted in New York Evening Sun, October 19, 1916.

[4] Jean Strouse, Morgan: American Financier (New York: Random House, 1999), 516.

[5] Cited in Deborah Parker, Becoming Belle da Costa Greene: A Visionary Librarian Through Her Letters (Florence: Villa I Tatti, 2024), 9.

[6] “The Letters of Belle da Costa Greene to Bernard Berenson,” I Tatti, accessed December 11, 2024, https://bellegreene.itatti.harvard.edu/resource/Start.

[7] The Pierpont Morgan Library: A Review of Acquisitions 1949–1968 (New York: The Library, 1969), xi.