This article first appeared in the journal Exhibition (Fall 2025) Vol. 44 No. 2 and is reproduced with permission.

It is no secret that museums are often under-resourced, with access programs among the first line items cut in the face of financial strain. In the 35 years since the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), many public and cultural institutions have worked to meet or exceed access requirements—while others continue to fall short. When these realities are coupled with political instability and threats to grant funding, there is a broad fear that the momentum accessibility initiatives have gained in recent years may come to a screeching halt. Though much remains unclear, one thing is certain—a monumental budget is not necessary to advocate for accessibility and serve disabled communities. The disability, history, art, and museum professionals cited within this article provide creative solutions for accessibility that can be adapted to a variety of budgets, demonstrating how access can be improved at all cultural institutions.

Mia Mingus, a writer, educator, and trainer for transformative and disability justice, asserts that disability and ableism are not secondary issues, although they continually get treated as such:

Disabled people are everywhere. We are one of the largest oppressed groups on the planet. We are part of political movements, even if you don’t know or don’t acknowledge that we are. No matter what community you’re working with, you are working with disabled people.[i]

Prioritizing accessibility is more important now than ever. According to the World Health Organization, “1.3 billion people experience significant disability”—that’s 16 percent of the world’s population.[ii] This number is only growing as the global population ages and rates of noncommunicable diseases, pollution, and violence increase.[iii]

All of this points to the importance of moving away from standard ableist practices within our institutions. Ableism, or discrimination and social prejudice against people with disabilities based on the belief that “typical” abilities are superior, is often fueled by a lack of disability literacy or careful consideration of the perspectives of disabled audiences, making education and communication about these topics crucial to inclusion as a whole.[iv] Museums, when they provide tools for access, are not catering to a few select groups, but better serving their entire audience for years to come.

Frameworks for Accessibility

Universal design (UD) refers to “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.”[v] There are seven basic principles of UD, all of which are are applicable to exhibition design:

- Equitable use: The design is useable for people with diverse abilities

- Flexibility in use: The design acknowledges a wide range of preferences and abilities

- Simple and intuitive use: The design is easy to understand, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language skills, or current concentration level

- Perceptible information: The design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the user’s sensory abilities

- Tolerance for error: The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of mistakes during use

- Low physical effort: The design can be used efficiently and comfortably with minimal fatigue

- Effective size and space for approach and use: The design is appropriately sized and adequate space is provided for its use, regardless of a user’s body size, posture, or mobility[vi]

UD enables exhibition designers to create spaces and experiences that are accessible to individuals across a wide spectrum of physical, sensory, and cognitive abilities.

Related to UD, Universal Design for Learning (UDL)—developed by CAST, an education research and development nonprofit—focuses on representation, action and expression, and engagement.[vii] Although UDL originated in a classroom setting, its principles have proven to have practical applications in the world of design and interpretation as well. According to the UDL framework, a design should provide multiple opportunties for engagement by assuming that users will possess a variety of levels of perception, experience, and comprehension. The design should cultivate multiple means of action and expression, capturing a learner’s interest by encouraging participation through more than one avenue. By presenting content in a variety of ways, a wider audience can be represented.[viii]

The UD and UDL frameworks remind us that accessibility cannot be treated as an afterthought, but must be an integral part of the exhibition-design process. Free resources pertaining to universal accessibility solutions are becoming easier to obtain, helping accessibility beyond compliance become more attainable.

Accessibility in Action

The following case studies demonstrate how various institutions have used UD and UDL principles to enhance access, how they did this with limited resources, and what the impact has been. The content of each case study is based on primary source accounts and interviews the author has conducted with museum professionals at each instutition. My goal is to provide a well-rounded picture of what affordable and accessible exhibition design might look like in a variety of settings.

Case Study 1: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

These examples at the Guggenheim achieve:

- Flexibility in use

- Equitable use

- Multiple means of engagement

- Multiple means of action and expression

Laura Sloan, Interpretation and Access Manager at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, spends her days finding ways to make exhibitions more accessible to museum audiences. The Guggenheim has various accessibility programs, including Mind’s Eye tours and workshops for visitors who are blind or low vision (BLV) that are conducted by arts and education professionals.[ix] Sloan’s team is always seeking out new and creative ways to share artwork with visitors in multisensory and low-cost ways. This includes creating tactile reproductions and 3D models of artworks with common craft materials like raffia, fabric, foam, paper, and feathers (fig. 1).

They also use Swell Touch paper, which expands along black lines when heated and generates a durable, tactile surface. Sloan describes these tactile models as, “an added element to the sensory experience that you cannot get through description,” benefiting all visitors, particularly BLV and neurodiverse audiences.[x] Before having the funds to purchase its own Swell Form Machine (around $1,500), the Guggenheim’s Interpretation and Access team partnered with local organizations to produce these reproductions. Partnering with local libraries and other creation spaces might allow smaller museums access to otherwise cost-prohibitive materials.

In addition to touch, the Guggenheim aims to engage visitors through a variety of other senses, sometimes even activating smell and taste through scratch-and-sniff stickers and candies. These simple and inexpensive items provide points of access that support multiple means of action and expression, something that is not always present within traditional exhibition design. Suddenly, a painting of two people at a table or a still-life of a bouquet of flowers becomes a multisensory experience, as Sloan shares:

There is this joy and surprise at the unexpected. “Oh wait, there is a smell on this thing you just handed me!” “Oh wait, we get to eat candy!” The unexpected can really bring joy and resonate within the group and also helps to bring people back for more. Creating this experience and community really adds to the overall experience that can help bring people together.[xi]

Case Study 2: Smithsonian American Art Museum

These examples from SAAM achieve:

- Equitable use

- Simple and intuitive use

- Perceptible information

- Effective size and space for approach and use

- Multiple means of engagement

- Multiple means of action and expression

- Representation

The exhibition Musical Thinking: New Video Art and Sonic Strategies was held at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in Washington, DC, from June 2023 to January 2024, exploring the powerful resonances between video art and popular music.[xii] The exhibition’s curator, Saisha Grayson, Curator of Time-Based Media at SAAM, kept accessibility in mind throughout each stage of the design process, resulting in an exhibition that centered accessible design.

In preparing for the exhibition, it was suggested to Grayson by The Shed—an arts and cultural center in New York—that 10 percent of the project’s overall budget should be allocated to accessibility: a useful rule of thumb for organizations of various sizes. Ultimately, two innovation grants from the Smithsonian’s central access department enabled Grayson to allocate 16 percent of the overall budget to accessibility-related initiatives.

These grants allowed Grayson to work with Motion Light Lab, a Deaf-led design group that is part of the National Science Foundation/Science of Learning Center on Visual Language and Visual Learning at Gallaudet University in Washington, DC. The group helped SAAM’s curatorial and exhibition design teams think through haptics and vibrational enhancements for a wheelchair accessible dance floor and seating, audio notes, and captions.[xiii] The grants also supported cross-departmental training for creating screen-reader optimized print and web pages, and the development and printing of a sensory map. Grayson also included work by Christine Sun Kim, a Deaf artist who uses scores, graphical notation, text, and performance to explore the Deaf community’s unique relationships with sound, in the exhibition (fig. 2).[xiv] Though some of the specific elements described might be cost prohibitive depending on total budget and grant availability, Grayson encourages museum professionals to allocate funds to accessibility whenever possible, stating, “it is important to continue to articulate that access is a significant part of exhibition design/museum work.”[xv]

Free and existing tools such as QR codes can be a relatively easy way for museums to make exhibition content more accessible, helping to provide visual descriptions, audio captions, and transcripts in a screen-reader friendly format that upholds the tenet of equitable use. Though they do require proper tagging, this is a relatively low-cost solution to share accessibility tools with BLV museum visitors. In Musical Thinking, QR codes were placed under the main section texts in the exhibition, as well as on the exhibition’s webpage (fig. 3). In future exhibitions, Grayson plans to make use of 3D QR codes, carefully planning their placement and perhaps providing a laminated booklet with raised QR codes and accompanying text.

Museums often cite artists’ intent as a reason not to caption video works; however, captioning is crucial to Deaf and hard-of-hearing users. Grayson’s solution to these competing needs demonstrates how creative thinking can enhance accessibility for all. The installation team ensured that captions did not go over the artists’ work by using projectors capable of projecting a 16:10 image to show 16:9 videos. This left a 16:1 band at the bottom for a second synced video file with captions to play. This innovative solution did not cost the institution any extra money, and can be easily achieved with readily available projectors.

Throughout the design process, Grayson’s team conducted feedback sessions with small groups of disabled users to gauge their needs and personal preferences. This included a recommendation to adjust the length of verbal descriptions, which helped to inform how those texts were written for use on the exhibition’s access guide webpages. They also received suggestions for alternative placements of QR codes within the exhibition that will inform future projects.

Case Study 3: Reid Park Zoo

These examples from Reid Park Zoo achieve:

- Flexibility in use

- Simple and intuitive use

- Perceptible information

- Multiple means of engagement

- Multiple means of action and expression

Reid Park Zoo in Tucson, Arizona, has a mission to connect people with animals, inspiring the protection of wild animals and wild places.[xvi] This requires the facilitation of accessible experiences for children and adults alike, taking the needs associated with various physical and cognitive disabilities into account. Jennifer Stoddard, Director of Education and Conservation, emphasizes the importance of keeping accessibility in mind during the creation and interpretation of exhibits and programs, stating “it is possible to take measures to make all of your programs accessible, and it is possible to do it with a lower budget.”[xvii]

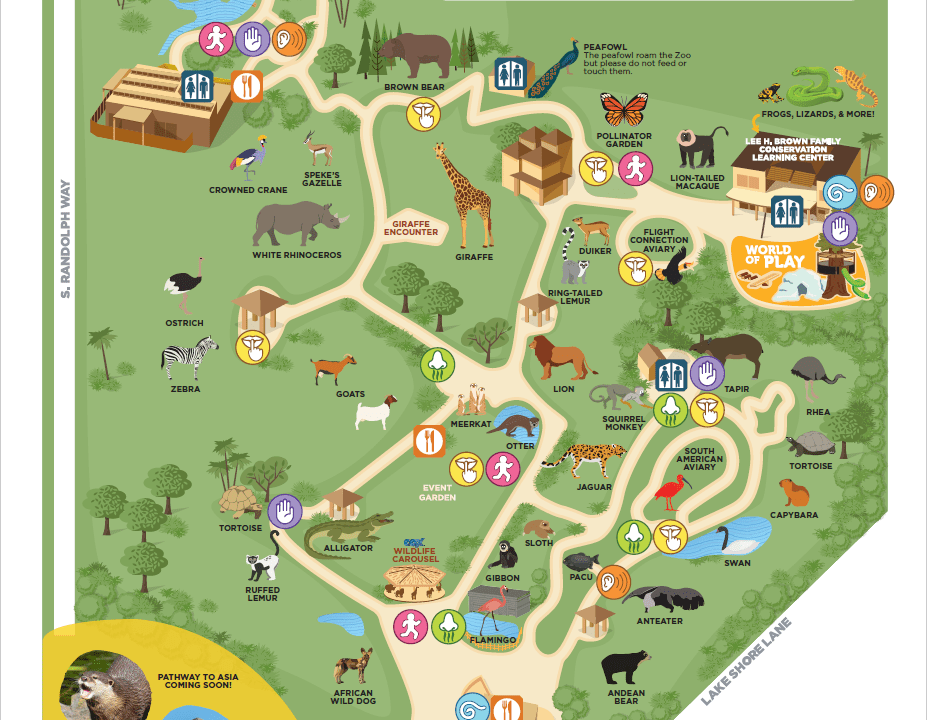

Many of the accessibility tools the zoo has implemented have been low to no-cost with high rates of usage, including a sensory guide, sensory bags, and audio tours. Former employee Molly Koleczek crafted the sensory guide to give visitors an idea of what to expect as they navigate the zoo, noting quiet, loud, and “stinky” areas, as well as spaces to move, touch, and cool down in the brutal southern Arizona heat (fig. 4).[xviii] The map is accompanied by a social narrative, allowing explorers to study their route before and during their visit. The guide is visually engaging and uses plain language, allowing a variety of ages to understand its content.

The zoo has also developed sensory bags that provide multisensory enrichment for visitors, including headphones and fidget toys. The bags can be checked out by guests, with the education team noting interest coming largely from K–4 audiences. This resource cost less than $100 to create and requires minimal staff time to maintain and sanitize. The zoo is currently reviewing its sensory bags to ensure they meet the needs of their diverse audience. They have also started to employ QR codes throughout their campus, enabling visitors to listen to audio tours that give more in-depth information on the animals and exhibits.

To further emphasize the importance of accessibility among their staff, Reid Park Zoo has developed relationships with community organizations that serve individuals with physical and cognitive disabilities. Employees are given the opportunity to attend in-kind trainings to increase their knowledge of disability and access initiatives. This training enables staff members to contribute to greater accessibility within each department, including exhibition design.[xix]

Case Study 4: Art Institute of Chicago

These examples from AIC achieve:

- Flexibility in use

- Simple and intuitive use

- Equitable use

- Tolerance for error

- Perceptible information

- Multiple means of engagement

- Multiple means of action and expression

- Representation

The Ryan Learning Center is the learning and creativity hub of the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC), providing opportunities for art-making and interactive experiences for all museum visitors, with a special focus on children, families, teens, students, and teachers.[xx] This free space, located at street level just before the ticketing counter, acts as the front porch of the museum, welcoming visitors to engage with art in a variety of ways. “Accessibility is baked into everything that we do; it’s threaded throughout our learning space,” shares Robin C. Schnur, Executive Director of the Ryan Learning Center.[xxi] The center’s design was recently refreshed to enhance accessibility—a project centered upon the principles of UD.

Like the Reid Park Zoo, the Ryan Learning Center has a sensory map and social narrative of the AIC available on its website. This project was largely driven by staff in the learning department, who conducted external and internal research to develop the map. Working alongside the museum’s communications and design teams, they created a clear and detailed guide that benefits all audiences.

Inside the Ryan Learning Center is the Multisensory Gallery, a small permanent installation that features 14 material samples commissioned from artists (fig. 5). Each sample highlights a single material and connects explicitly to an artwork in the collection. The label for each sample includes content in braille, an image of the reference object, and a guide to let you know where to find that object in the museum. Visitors are invited to look closely using a magnifying glass and to touch the material samples. Though not all institutions have the means to commission artists to create tactile samples, a similar experience can be achieved by assembling a “touch collection.” Such a collection might include artists tools—like brushes that have different types of bristles—or materials like stone, ceramic, or canvas. Schnur’s team has observed that the space helps visitors to make deeper connections with artworks, allowing them insight into how things might feel, smell, or sound when they visit the main galleries.

The AIC also developed accessible wayfinding signage in the Ryan Learning Center. Based on research done by staff, the museum developed signs that communicate in multiple codes that are not solely dependent on English language fluency, through their use of color and contrast, font style and size, and the use of icons and symbols to communicate information (fig. 6).[xxii]

Nothing About Us Without Us

Listening to and uplifting the voices of disabled community members and professionals is the most pertinent way to guide accessible display across a variety of budgets. Sav Schlauderaff, Access Consultant at the Disability Resource Center at the University of Arizona and Disabled Staff & Faculty Coalition Co-lead, shares:

When it comes to accessibility, sometimes people just don’t know where to start. [It is important] to have conversations with staff so people are more comfortable with talking about disability and interacting with disabled people.[xxiii]

This foundational step can help open up greater conversations about disability, inspiring museum professionals to think more critically about how to make their exhibition spaces more accessible.

These conversations can also help to combat harmful misconceptions about the ways disabled people interact with museums. Schlauderaff states, “There is an assumption that disabled people are not coming in—or disabled people might make the decision not to come in because the space is not accessible.”[xxiv] Similarly, Alisha Vasquez, a self-described krip, historian, and co-director of the Mexican American Heritage and History Museum, shares, “Even when we are visible, we are kind of invisible. If we are not there, people are not going to know that we are missing.”[xxv]

In a historically and continually ableist society, it is understandable that some disabled individuals may feel like museums are not for them. To combat this, it is important for museums to clearly indicate the tools they have available. moira williams, disabled Indigenous artist, cross-disability cultural activist, and access doula, encourages museums to provide an accessibility menu of their offerings, “letting people with disabilities know the ways in which they are being considered and welcomed to make informed choices” related to their museum visit.[xxvi]

williams further emphasizes the importance of accessibility by uplifting the work of disabled curators and artists. “There is power in co-creating accessibility with mixed abilities and disabled people. This means we are getting the access we desire.” williams works to create exhibition spaces that are accessible across a spectrum of disability, including being “inclusive of blind, Deaf, low-sighted, low-hearing, and—most neglected—intellectually disabled folks” (fig. 7).[xxvii]

Disabled Mestize (Indigenous/Latinx/White) poet, author, facilitator, and visual artist Naomi Ortiz further suggests adjusting the hang height of art installed on the wall, allowing wheelchair-users and people of short stature to see the work centered. Ortiz also recommends transparecy when art is explicitly about disability, stating, “museums should [say] if the artist is disabled or [indicate] their relationship to disability.”[xxviii]

Conclusion

Just because accessibility can be facilitated in a low-cost way does not mean that should be the end goal. Accessibility is a worthwhile investment and—as several of these case studies come from museums with relatively large budgets—it is clear that our sector’s overall commitment to inclusion demonstrates room for growth. Low-cost solutions are a great place to start, but the scaling and integration of access into exhibition and budget planning needs to become standard practice for truly equitable museum experiences to become commonplace.

The commitment and care exhibited by the professionals interviewed for this article draws attention to another important part of the cost equation: time. Building relationships and trust with disabled community members does not happen overnight, and the creation of each exhibition design element takes time and effort. Carving out time to invest in accessibility may seem daunting, but it is essential if we are to reduce ableist tendencies in our museums.

As a resource for readers looking for a reminder of what to consider as they begin to incorporate more UD principles into their work, I have created the Exhibition Design for All Toolkit. This checklist is based upon the principles of UD and UDL, allowing museum practitioners to improve upon and rate the accessibility of their exhibitions. It can be used to evaluate the level of accessibility within exhibitions and to propose solutions for designers to implement in the future.

In the midst of an administration that upholds anti-disability rhetoric and policy, it is essential that museums take a stand to uphold accessibility and access for all. Exhibition designers have the ability to foreground access and instill confidence that the inclusion of a variety of perspectives is not only possible but powerful. As Schlauderaff says, “Without the budget, it can be hard to provide more formal types of accessibility. However, it is possible. Things won’t be perfect but it will be better than it was.”[xxix] No matter an institution’s size or budget, incorporating low-cost exhibition design elements for access is a crucial first step toward inclusion.

Violet Rose Arma (she/her/hers) is Curatorial Assistant & Administrative Support at the University of Arizona Museum of Art (UAMA) in Tucson, Arizona. violetrarma@arizona.edu

[i] Mia Mingus, “Access Intimacy, Interdependence and Disability Justice,” blog post, Leaving Evidence, April 11, 2017, https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2017/04/12/access-intimacy-interdependence-and-disability-justice/.

[ii] “Disability,” World Health Organization, January 27, 2020, www.who.int/health-topics/disability.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Ashley Eisenmenger, “Abelism 101,” Access Living, December 12, 2019, https://www.accessliving.org/newsroom/blog/ableism-101/.

[v] Sheryl Burgstahler, “Universal Design: Process, Principles, and Applications,” accessed July 15, 2025, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED506550.pdf. It is worth noting that organizations such as the Institute for Human Centered Design have adopted the term inclusive over universal design, noting, “inclusive design more directly states a commitment to not only acknowledge but celebrate diversity.” “Inclusive Design: History,” Institute for Human Centered Design, accessed July 15, 2025, https://humancentereddesign.org/inclusive-design/history.

[vi] “The 7 Principles,” Centre for Excellence in Universal Design, accessed July 15, 2025, https://universaldesign.ie/about-universal-design/the-7-principles.

[vii] “The UDL Guidelines,” CAST, 2024, https://udlguidelines.cast.org/.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] “Mind’s Eye,” The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, Accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.guggenheim.org/accessibility/minds-eye.

[x] Laura Sloan, interview with the author, February 7, 2025.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] “Musical Thinking: New Video Art and Sonic Strategies,” Smithsonian American Art Museum, accessed July 15, 2025, https://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/musical-thinking.

[xiii] Saisha Grayson, interview with the author, January 31, 2025.

[xiv] “Accessibility: Christine Sun Kim. For the exhibition Musical Thinking,” Smithsonian American Art Museum, accessed July 15, 2025, https://americanart.si.edu/exhibitions/musical-thinking/accessibility/christine-sun-kim.

[xv] Grayson, interview.

[xvi] “About,” Reid Park Zoo, accessed July 15, 2025, https://reidparkzoo.org/about/.

[xvii] Jennifer Stoddard, interview with the author, February 4, 2025.

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] “Ryan Learning Center,” Art Institute of Chicago, accessed July 15, 2025, https://www.artic.edu/ryan-learning-center.

[xxi] Robin C. Schnur, interview with the author, February 6, 2025.

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] Sav Schlauderaff, interview with the author, March 13, 2025.

[xxiv] Ibid.

[xxv] Alisha Vasquez, interview with the author, March 24, 2025

[xxvi] moira williams, interview with the author, March 25, 2025.

[xxvii] Ibid.

[xxviii] Naomi Ortiz, interview with the author, March 25, 2025.

[xxix] Schlauderaff, interview.