Maybe you’ve heard the quote “the only constant is change,” which I believe is true. Change is always happening, so much so that life and work often feel more topsy-turvy than constant.

For a while, the constant change we lived with was in reimagining our post-pandemic life and work. While many of us have settled into a steadier routine now, we are still figuring out where, when, and how we work most effectively.

I recently spoke with Becky Beaulieu, CEO of the Taft Museum of Art, who is enthusiastic about these systems and how she can innovate on them at her museum, including a noteworthy recent change: shifting to a four-day workweek.

Adam Rozan: Thanks for talking with me today. Please tell us a little about yourself.

Becky Beaulieu: My name is Becky Beaulieu, and I’m the Louise Taft Semple President and CEO at the Taft Museum of Art in Cincinnati, Ohio. I started my career almost twenty-five years ago in education, followed by curatorial work during my first master’s degree in art history [at UW-Milwaukee]. My second [master’s] came later, in arts administration at Columbia. … Then, I moved to Boston for my PhD. And while I was doing my doctorate, I first ran a small historical society, and then I moved up to Maine, and I worked at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art as their associate director.

AR: Bowdoin is a beautiful campus and has an excellent museum. Plus, some fascinating history with Joshua Chamberlain, if I’m correct.

BB: That’s right! I was on the board of the Pejepscot Historical Society, which maintains the Joshua Chamberlain House. That’s when I became interested in strategic planning, administration, and financial management. My time at Bowdoin is where I began to take a more active role in finance. It’s funny; most people [have] heard of me because of my work in finance, teaching, and writing. My first book was on museum finances for historic houses, and my second was on endowments.

AR: Two masters, a PhD, and two books?

BB: Yes, and I took all the work that I’ve done over the past ten years or so with teaching and workshops, and I turned that into what’s going to be my third book, 75 Most Asked Questions About Museum Finance, which will be published through the AASLH press at Bloomsbury.

AR: If we were to generalize, you could say the field is divided into two groups: the objects and the people. However, when talking with you, I realize a third category is necessary. Let’s call it governance.

BB: I agree. You could divide the field into those who are passionate about the objects and those who are passionate about the public. But I’d have to say, there are enough of us for a third category. I wouldn’t call it governance, but systems.

AR: I like that. So, we have three types of individuals drawn to museum work, but maybe success comes from the blending or respect for all three. Let’s discuss the process you and the staff at the Taft used to develop your unique way of working, along with some of the structures involved.

BB: Everything began with our strategic planning work, which I’m proud to say was a 100 percent participatory process and included over seven hundred community voices. We also managed to tackle some unresolved issues, such as a compensation study that helped us align staff pay with market rates, raise hourly wages, and enhance benefits. Even the language we used was updated. Additionally, we conducted an equity study across the staff, partnering with a firm called Ellequate, which helped us better understand workloads organization-wide and identify areas where fairness was lacking. This process allowed us to see, for example, which benefits and services staff knew about and which they did not, along with what was important to them and what wasn’t. This was crucial for the staff and also enabled us to identify potential cost savings.

AR: I can imagine it was impactful for the organization and meaningful for staff, especially if you were offering benefits that people either didn’t know about or didn’t take advantage of. Meaningful work for sure, but also time-consuming, especially since the process involved all staff, board members, volunteers, and community members. My question is, how did the organization find the right balance between daily operations, core work, and this institutional assessment?

BB: We’re a two-hundred-year-old building, so we’re always dealing with some facility issues, and like everyone, we’re also coming out of the pandemic, which means rebuilding our revenue model. We’re rethinking our café, we’re hiring for some new positions, updating some policies, and on and on. It’s an all-cylinders mentality. To be clear, it’s not like we had time on our hands. [Instead, we were] saying, “We’re going to all work really hard, and here’s the tradeoff: if you are on the team where we’re all working hard together, this is what we’re going to show you. This is how we’re going to show that we value you.”

AR: So you had a truly open process, shared purpose, goals, etc. I imagine that there was an ongoing discussion about what you prioritize now versus what can wait for later.

BB: We can’t change every process at once, and there were certain things that we had to prioritize, and we continue to do so. For instance, when we changed our donor management software, we had at least five departments involved in that decision-making. We try to gather as many different perspectives as possible to inform a decision, which is really helpful. And our people aren’t alarmed when they’re asked to come to a meeting for something. They now understand that they’re weighing in, which builds confidence for us at a comprehensive institutional level.

AR: You also implemented a four-day work week. Can you talk about how this came to be and what it entails?

BB: I had read a book about a four-day workweek [Shorter: Work Better, Smarter, and Less by Alex Soojung-Kim Pang], and I thought it was an interesting idea. It just so happened that we were in the process of transitioning our [employee] benefits structure. And because we were making changes to create a more equitable time-off schedule, we would no longer have indefinite banked vacation time for the longest-serving employees. It used to be that if you were here forever, you just had tons of vacation time. Also, when you started here, you had no vacation time, as vacation hours had to be accrued. And that’s not fair. It’s also a financial liability for the organization because [annual leave is] something that has to be paid out if someone leaves [depending on your state].

I talked to my HR director, and together we came up with the idea. We said, “Well, here’s something interesting—we’re both kind of taken with this.” We had conversations about the idea that [the world has] created so many efficiencies in recent decades. We now have these platforms like Microsoft Teams to keep in touch with each other when we’re not on-site.

And so that’s when we [said,] “Why don’t we talk to the people who have all this time banked?” … People at different levels, people in different departments and with different titles. And we asked them if they would be willing to pilot a study where they use vacation time they have built up to try working four days a week, and … that structured vacation time reduced the [leave] banks and thus some of that financial liability.

And so that’s what we did. We ended up having nine people participate, and so for thirty-two weeks, they worked thirty-two hours per week and filed a vacation day for the fifth day.

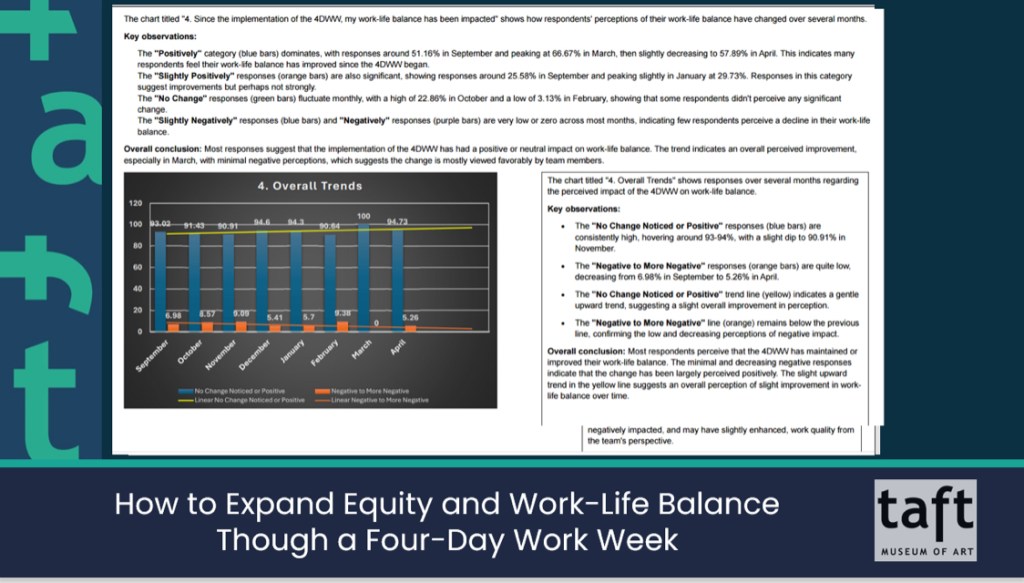

At the same time, we worked with a sociologist who conducted weekly check-ins and data collection using a Likert scale—“on a scale of one to five, how productive are you?”—and provided qualitative feedback. We also surveyed their supervisors, anybody reporting to them, and their peers to determine any weak spots.

That original pilot not only gave us the opportunity to try a thirty-two-hour workweek—which we could have stopped at any time, since it wasn’t policy or anything set in stone. Yet because the study consisted of those who had time banked that exceeded our new threshold, there was no resentment regarding the initial pilot group. Then we ran the experiment again, with some additional staff, and so on. We took our time, but we got everybody on board.

AR: What I love about this is that you tested the project, went slowly but deliberately, and even worked with a sociologist. Speaks volumes to the process.

BB: Thank you. We also keep the topic on the agenda at our leadership team meetings once a week. We do monthly surveys. We report out to the staff every quarter. Our HR director has been meeting with team members to determine, “OK, where are there bottlenecks, where’s the pressure point?”

And a lot of times what we found is it’s not about the workweek changing. The focus has been on where is there an inefficiency that we’ve identified. Because we’ve taken the lid off, and we’re looking so closely at our operations and processes. It has been flat in terms of budget. Everyone’s making the same amount of money as they did with a forty-hour workweek, and people are happier.

The fifth day—we call it a “Someday.” And that comes from Alex [Soojung-Kim Pang], who wrote the book Shorter, and that “Someday” is where you can do things that are just for yourself.

AR: My next Someday will be a visit to the Taft Museum. Thank you so much for chatting with me about everything that’s happening at the museum.