I’ve long admired the creativity and ingenuity of the Manchester Museum—following their exploits from inviting a hermit to live in the museum for forty days and forty nights and while engaging the public in an examination of what might be removed from the collections; to recruiting a fashion design firm to plan the reinstallation of their natural history collections. Now they’ve tackled the haptic frontier—using technology to simulate the experience of touching objects that visitors are not allowed to actually handle. Today Sam Sportun, collection care manager and senior conservator at the Manchester Museum, tells us more about this adventure into the realm of digital digits.

In recent years, Manchester Museum has pursued a philosophy of making more of its collection available for visitors to handle and touch through object handling sessions and tactile displays. As is well known, this approach benefits all visitors, as the sense of touch physically connects the visitor to the object and enhances an intuitive and natural curiosity to learn more. However, as a conservator I also know that some objects will not survive long term use as a handling object. Complex, beautiful objects often have the most captivating histories, but when displayed behind glass, they can be very difficult for a visually impaired visitor to appreciate.

With funding from the Stavros Niarchos Foundation, we tackled the challenge of providing access to objects that can’t actually be handled by developing a Haptic Interactive. Haptics consist of a touch-enabled computer system which allows the user to investigate and explore the topography of an artefact within a 3-dimensional digital environment through a tactile feedback stylus. The Manchester Museum’s interactive provides a digital experience using objects from our new Ancient Worlds galleries.

We realized that the end user had to be involved in the process of developing the interactive from the very beginning. Over the past 18 months Christopher Dean and I worked with an enthusiastic focus group from Henshaws Society for Blind People. Members of the focus group chose three objects for the interactive: a faience shabti [380-343 BC], Greek jug [500-475 BC] and Pre-Dynastic hippo bowl [4000-3500 BC]. Even more importantly, they helped to guide us through the process of creating an easily navigable 3D digital space.

|

|

Laser scanning the pre-dynastic hippo bowl (4000-3500BC)

|

The haptic interface enables users to explore the digital scanned form of objects, using their sense of touch. We enhanced the digital content with sounds, video and the spoken word, creating a rich experience as the object’s story unfolds. We are also developing activities within the interface that enable the user to explore the silhouette of an object to enhance their understanding of its overall form. A portable version of the system is used for outreach to groups that may have problems getting to the museum.

|

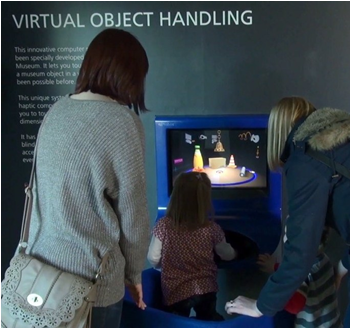

| Haptic unit in the new gallery |

We found that when visitors use the device for the first time, unless they take time to explore and understand this space, the experience can feel unrewarding. So we introduce users to the 3 dimensional digital space with an introductory screen that uses sound and everyday objects. Once passed this first screen the interactive has a series of “rooms” which deal with different aspects of the objects history, manufacture or use.

Very intriguing, however I have a question: How does a visually-impaired person navigate the screens in order to select and "touch" an object?

Good question, Sara. Sam Sportun, author of the post, is away until next week, but I'll ask her to answer you then.

Posted on behalf of Sam Sportun:

"Hello Sara,

The visually impaired person uses the hand held stylus, by holding the ball of the stylus between the fingers – the ball on the screen mimics that of the ball in the hand- for the visually impaired, the user will feel a resistance when the ball on the screen comes into contact with the surface of the surrounding "room"or an object.

Our user group asked for another element within the interface to help them locate the object. So Chris introduced a grooved ring at the base of each of the "rooms" that can be felt and gives a reference to the entire space and the objects are either in the centre of this ring or above a reference depression point in the ring. This can be seen in the image as a blue ring and the depressions in the ring are red. These depressions in the ring also allow the user to move between screens.

The other important element was using sound in the digital space and vocal instructions. The addition of sound also gives an indication of the objects material qualities. There is still much to do but we have now got a platform to build on and add to.

Thank you for the question, Sam"

Hi

This looks great. I'm wondering though whether the 3D scans couldn't just be used to 3D print the objects for people to handle without using a haptic device?

I work with visually impaired students who would welcome such a facility.

Hi Stillimage–it's a good question: what are the tradeoffs between 3D printing and haptic tech, and when is each a good option for accessibility? I will invite Sam, and others, to weigh in.

Hi Stillimage,

There is definitely room for both types of interactive – replicas can be very useful for certain types of activities – especially understanding the form of something; but to get further information about the object the interaction needs to be facilitated – or have other sources of information close at hand (that is partly why I have started developing the digital touch replicas).

Space is another issue -most museums do not have enough room for their accessioned collections – never mind another collection of replicas. The haptics interface allows for collections of objects to be displayed – from anywhere in the world and the objects can be large or small and scale is not an issue – although it needs to be made clear in the interface the actual size of the real object (macro or microscopic).

The Haptics work has been going well – we were invited to the Zeroproject Conference that was just held in Vienna to present our work as a chosen Innovative practice and was one of 4 cultural projects chosen that were seen as ways developing practice in a way that was overcoming barriers for those with disabilities. We have also been working with Yale Peabody and they have given us a digital object to include in our haptic device and a couple from the British Museum.

We are doing quite a lot of work with touch sensitive replicas at the moment and I have started a part time PhD at Loughborough University looking at their development. We have had a digital touch prototype replica of an Ancient Egyptian Stela on the gallery for 2 years now (and it is still working!). The replica has strategically placed sensors, which trigger sound and image files relating to the carved detail, playing on adjacent screen, allowing the visitor to interrogate complex themes, symbols and narratives in a self-guided intuitive exploration. The information can be updated and allows for a number of narratives themes to be added to the object, as well as translation.

Another project underway is working with a volunteer at our museum (Joe) who has cerebral palsy, to make these touch replicas more beneficial for our physically disabled visitors to encourage participation and learning when they are on the gallery. Happy to talk further about the work,

Best Wishes, Sam