In our always-on, hyperconnected world, people are beginning to assess the potential downside of being tethered to the Internet and hand-held devices. Turns out, however, that digital detox isn’t always easy; the umbilical Internet is literally addictive and cutting the cord takes real effort. The desire to unplug opens opportunities for museums to flaunt one of their classic strengths, as places of contemplation and retreat.

“I think this could be the way we live in the future: Connectedness and disconnectedness will coexist in peaceful harmony, with unobtrusive devices and mind sets that consciously (and unconsciously) shift as healthy lifestyle choices. People tomorrow may take an hour or two every day to be unplugged, free from digital input.” —Kathleen McLean, Principal, Independent Exhibitions

It’s easy to cite statistics about the increasing ubiquity of digital devices in modern life—not just in the United States or other developed countries but across the entire world. Americans spend more time than ever experiencing the world through electronic screens, voraciously consuming and sharing, via TVs, game consoles, computers and various portable devices. Experts project that 57 percent of the U.S. Internet population (age 8–64) will own a smartphone by spring 2013, and more than two-thirds of smartphone owners already say they “cannot live without” the devices. (A third of adults also say they would rather give up sex than their cellphones, at least for a week!) Now tablet use is booming, and futurists imagine a plausible future of wearable computers and bio-implants, where everyone is plugged in all the time.

Many museums are adapting to this ubiquity by creating new opportunities for engagement that can only be experienced through connected devices. These include experiments in augmented reality and charitable giving via cellphone (two trends we explored in TrendsWatch 2012), location-aware technologies (see page 24), QR codes or other information triggers in the galleries, phone-based tours, games, social media sites, etc. When people bring their own devices to museums, they expect to be able to connect. Public demand for mobile data services has already convinced many coffee shops, hotels, conference centers, airports—and now museums—to offer free, reliable wi-fi networks. (The most extreme example of this in the museum world is probably the wi-fi hotspot on an ass introduced by a living history museum in Israel, designed to make it easier for visitors to tweet and update their social-media accounts while interacting with costumed interpreters in the middle of a desert.)

But if the pendulum has swung towards hyperconnectivity, we also see signs of a swing in the opposite direction—a backlash against digital immersion and in favor of quiet contemplation and face-to-face contact. The backlash embraces educators who worry about the diminished attention span and social skills of their students, moms who see “both the opportunities and challenges that result from the proliferation of technology,” museum traditionalists who want to keep the visitor’s focus on authentic objects and committed humanists of all stripes. Even the most connected generation in America is experiencing connection fatigue, with 60 percent of 18- to 29-year-olds saying they “feel guilty” about the amount of time they spend on cell phones, social media sites and the Internet.

Commercial marketers have been quick to act on the insight that “consumers rely so heavily on multi-screen search, e-mail and social networks for negotiating their personal and professional lives that there is a growing desire to take a break from being ‘always on.’” Global brands like McDonald’s now promote family time away from cellphones. A restaurant in Los Angeles offers a discount for diners who are willing to surrender their cellphones for the duration of a meal. Hotels and resorts are offering special unplugged vacations; one resort even calls it a “digital detox.” A monastery in Washington, D.C., has created a rental “hermitage” on its grounds that was booked solid as soon as it opened last fall. Meanwhile, designers have introduced new technologies to discourage digital connections (e.g., a special wallpaper that blocks wi-fi signals) and encourage quiet social interactions (e.g., a portable “confession booth” designed for privacy and seclusion in noisy shared spaces).

WHAT THIS MEANS FOR SOCIETY:

- There is contradictory evidence about the impact of hyperconnectedness, especially when it comes to children and young adults. Smartphones and the Internet either sap their attention spans or turn young people into sophisticated information-seekers and problem solvers. Social networking can either promote maturity and sympathy or “kill our desire to connect,” leading to a kind of fidgety loneliness in the midst of constant updates and “likes.”

- As a society, we may have to find ways to recognize digital addiction and provide support for people to disconnect, such as the nonprofit organization Reboot’s recent National Day of Unplugging.

- Involuntary disconnection may be a small bright spot in the aftermath of increasingly frequent natural disasters. After Hurricane Sandy in October 2012, thousands of preteens, teens and their elders found themselves unplugged—and they survived. While it “drove some children crazy … others managed to embrace the experience of a digital slowdown.”

“This is a great opportunity for museums to evaluate how those with and without devices experience exhibitions and whether educational and/or other objectives of exhibitions or other programming are realized with and without the devices.”—Pat Kociolek, Director, University of Colorado Museum of Natural History

WHAT THIS MEANS FOR MUSEUMS:

- Museums may be caught between contradictory demands for connectivity and contemplation inside the galleries. Temporal or spatial partitioning (e.g., limits on where and when visitors can use digital devices) may be necessary to navigate these conflicting expectations.

- However, museums should be wary of sending mixed messages, such as providing interpretation via high-tech devices on one hand, while banning teens from bringing phones into the museum (or telling adults to switch off their phones) on the other.

- Museums should still pay attention to all the projections about mobile devices, embedded devices, augmented reality, social media, etc., as highly likely futures. But they should also pay attention to the educators, critics, philosophers, museum-goers and others who lament the loss of quiet, contemplative, unconnected spaces in society such as those that museums have traditionally provided.

- The “off-line niche” may be a viable refuge for museums that find themselves losing the connectivity arms race with the media-saturated world outside their walls, as they compete with other museums as well as alternative leisure activities. This competition is especially challenging for smaller and poorer institutions, as summarized by a staff member at the Fort William Henry historic site in upstate New York: “Once one museum does, others don’t want to be far behind. When kids come, a lot of them have seen the fancy stuff. We don’t want to look dated. For the younger generation, they don’t necessarily know how to relate to some of the older presentations.” If you can’t win the game, change the rules.

MUSEUMS MIGHT WANT TO …

- Remember that visitors come to museums with different preferences for noisy, connected, quiet and solitary experiences. Museums can find ways to satisfy these different preferences with specific times or places for “unplugged” visits—such as Un-tech Tuesdays (“don’t bring your own device”) or galleries in which mobile devices are never allowed. Following the lead of the travel industry, museums could provide options to voluntarily unplug, encouraging visitors to deposit their mobile devices in lockers when they enter, or providing individual phone vaults.

- Become unapologetically disconnected, marketing the museum as a place where people can always unplug from the Web to concentrate on the exhibits and each other. These museums can be cheered by a recent study showing that solitary visitors to art museums (i.e., no companions or even devices) “spend more time looking at art and … [experience] more emotions.”

- Decide whether they have a role to play in sharing the latest thinking on the pros and cons of constant connectivity, equipping visitors to make informed choices for themselves and for their families about appropriate limits to screen time.

MUSEUM EXAMPLES:

• Museums are creating interactive physical experiences that are so engaging there is no time to tweet or text in the midst of the action. For example, the National Building Museum invited architects, landscape designers and building contractors to create a 12-hole mini-golf course that challenged visitors to break par 4 while demonstrating elements of urban design.

• Eight museums have been recognized by the Association of Children’s Museums “Good to Grow” initiative for their work to promote healthy behaviors for kids, including the reduction of screen time (TV, computers and phones).

• Bucking trends (and arguably trying to stem a relentless tide), the Musée d’Orsay has banned all photography in the museum, including non-flash, cell phone pictures of non-copyrighted works. (This hard-line stance spawned a movement, the Orsay Commons, that periodically organizes mass disobedience to protest the ban.) While photography per se is not a connectivity issue, the huge boom in amateur photography has been driven by the desire to share experiences with friends in real time via social networks like Facebook, Flickr and Instagram.

• The Vatican Art Museum has “installed” two priests to answer questions (as docents often do) but also provide aesthetic and spiritual guidance.

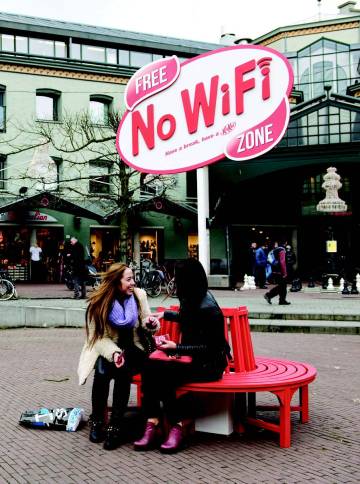

Kit Kat sponsors wi-fi-free zones in downtown Amsterdam.

FURTHER READING:

Sight, a short film by Eran May-raz and Daniel Lazo, creatively explores the consequences of a world where too much digital connection overwhelms our relationship with other people and the physical world.

Pico Iyer, “The Joy of Quiet,” New York Times (Jan. 1, 2012).

Kathleen McLean and Wendy Pollock, The Convivial Museum (Association of Science-Technology Centers, 2011).

George Prochnik, In Pursuit of Silence: Listening for Meaning in a World of Noise (Anchor, 2011).