Phil and I have been collecting notes on exhibits that help society think about the future. For example, this 2010 exhibit of futuristic art in London; “Lifestyle 2050” at Japan’s National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation; or Future Earthat Science Museum of Minnesota –an ecological look at the world in 2050. We also look for exhibits showing how people in the past looked at the future. (Which is even more fun, because you get to both revel in nostalgia and snark at what they got wrong.) For example, the current Never Built: Los Angeles at the Architecture and Design Museum, or the National Building Museum’s Designing Tomorrow: America’s World’s Fairs of the 1930s, This week’s post by Colin Robertson, Charles N. Mathewson Curator of Education at the Nevada Museum of Art, is about an exhibit from the latter category—futurist visions from the past.

|

| Photograph by Jamie Kingham |

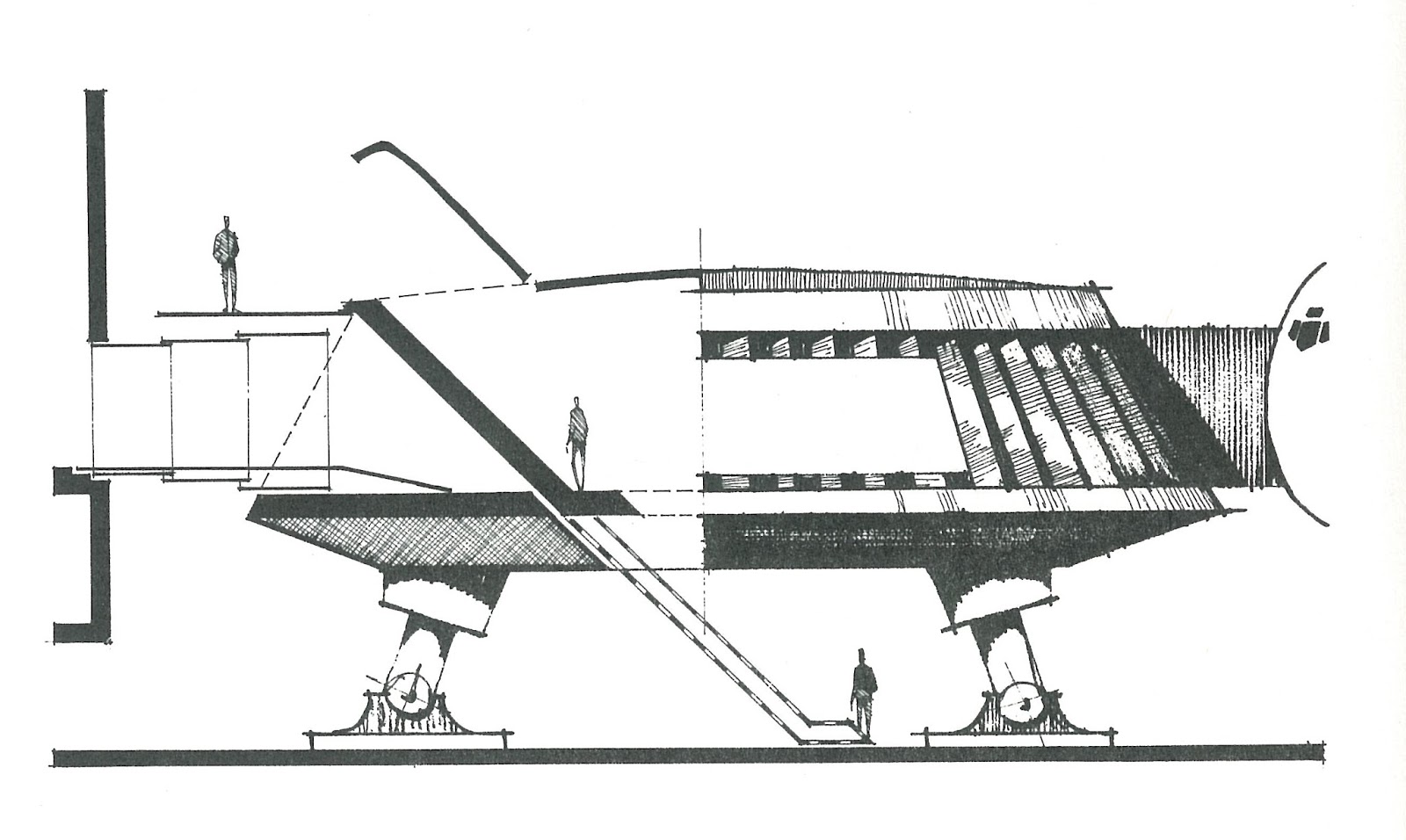

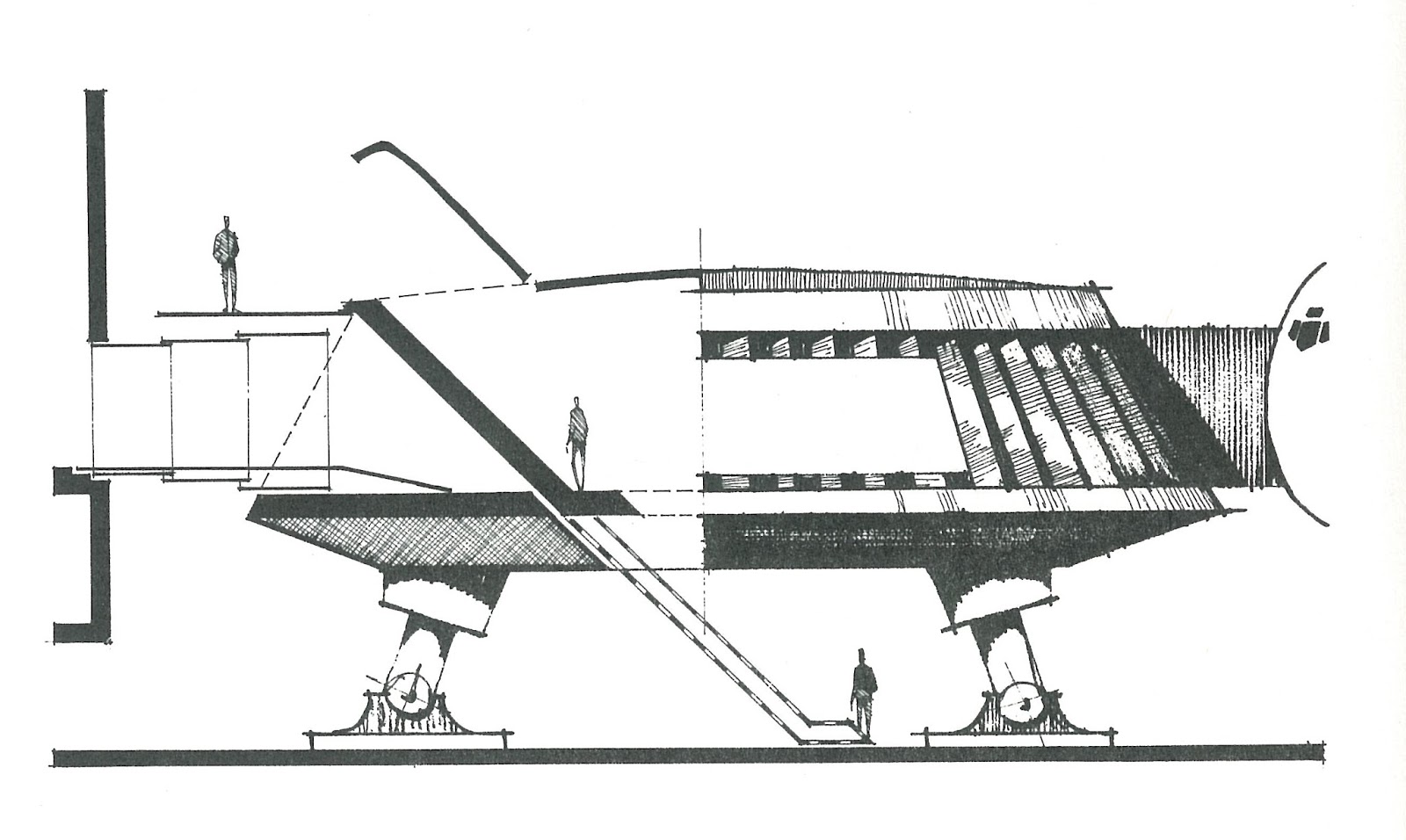

The current feature exhibition at the Nevada Museum of Art, Modernist Maverick: The Architecture of William L. Pereira, presents a swath of the American architect’s most important projects from his fifty-year career, highlighting the iconic structures he designed such as the futuristic Theme Building at the Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), the Transamerica “Pyramid” in San Francisco, and the science fiction-y Central (now Geisel) Library building on the campus of the University of California, San Diego. The exhibition also examines his quieter but no less important master plans for Southern California’s historic Irvine Ranch, the University of California, Irvine campus, and LAX. The curatorial framework for the show, in concert with its exhibition design by Nik Hafermaas | Uebersee, casts Pereira as an architectural futurist—that is, as an architect whose greatest contributions may not have been the iconic buildings or places he designed, but the processes of designing architecture at all scales (buildings, campuses, cities, and environments) for future changes and needs that he could not predict but only imagine.

|

| Image courtesy of Johnson Fain Archives |

In the mid-1950s Pereira and his then-partner Charles Luckman were commissioned to design a new master plan for the updating and enlargement of the Los Angeles International Airport. It was in scope, scale, and budget, the largest project to date for the youthful partnership. Some sixty architects and planners from the Pereira and Luckman office worked exclusively on the project for over two years. Their task, less than a decade after gravel runways were still in use at LAX, was to design plans for airport facilities to accommodate the 18 million passengers the airport authority anticipated would be traveling through LAX by 1980, and to imagine a new airport for the Jet Age. Their proposals included plans for a large, central domed structure that would have enabled passengers to leave their cars in parking structures on-site and circulate through the airport and out to the concourses without further encountering automobiles. Anyone who’s been to LAX knows that this is decidedly not the way things work there today.

|

| Image courtesy of Johnson Fain Archives |

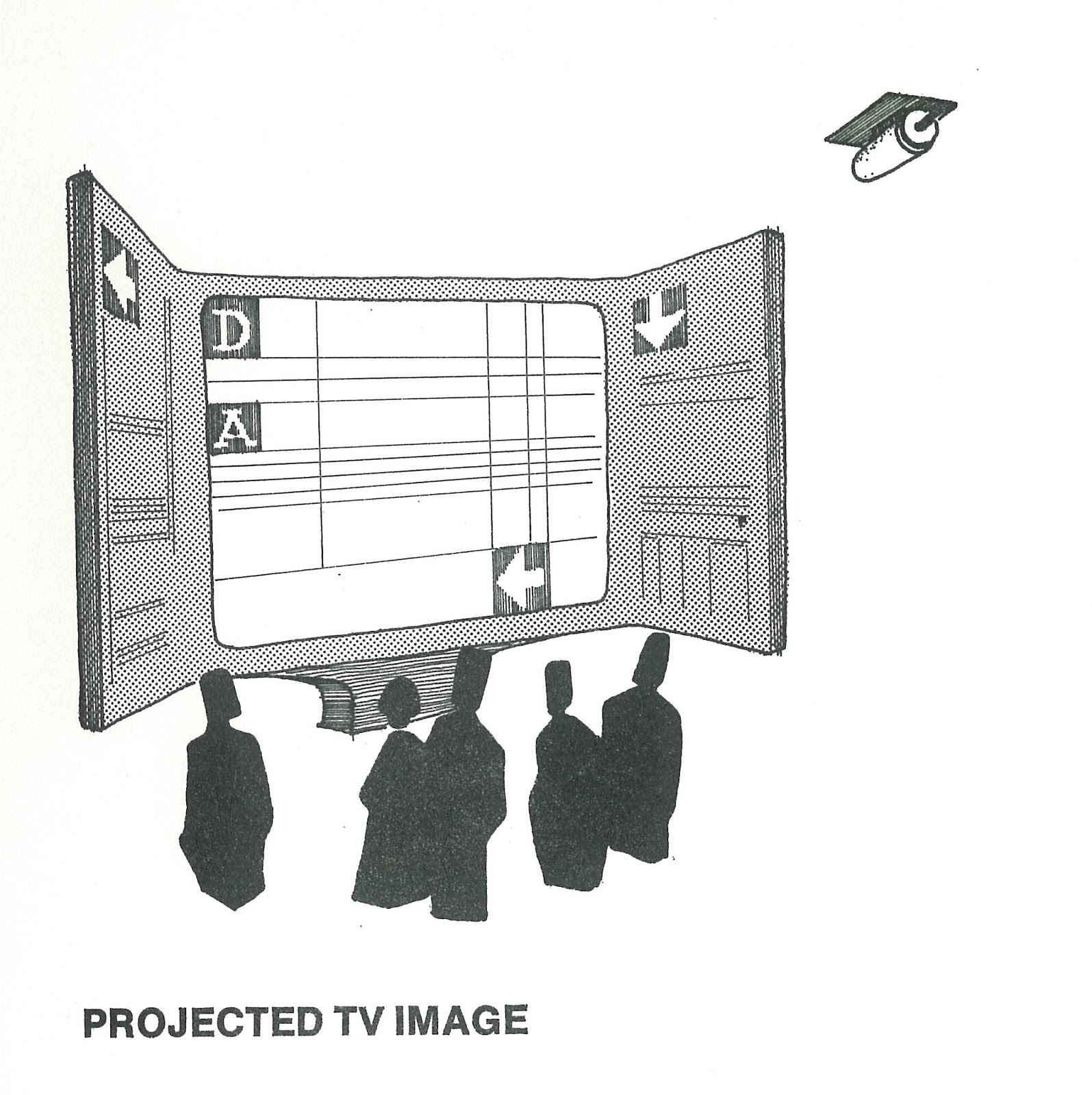

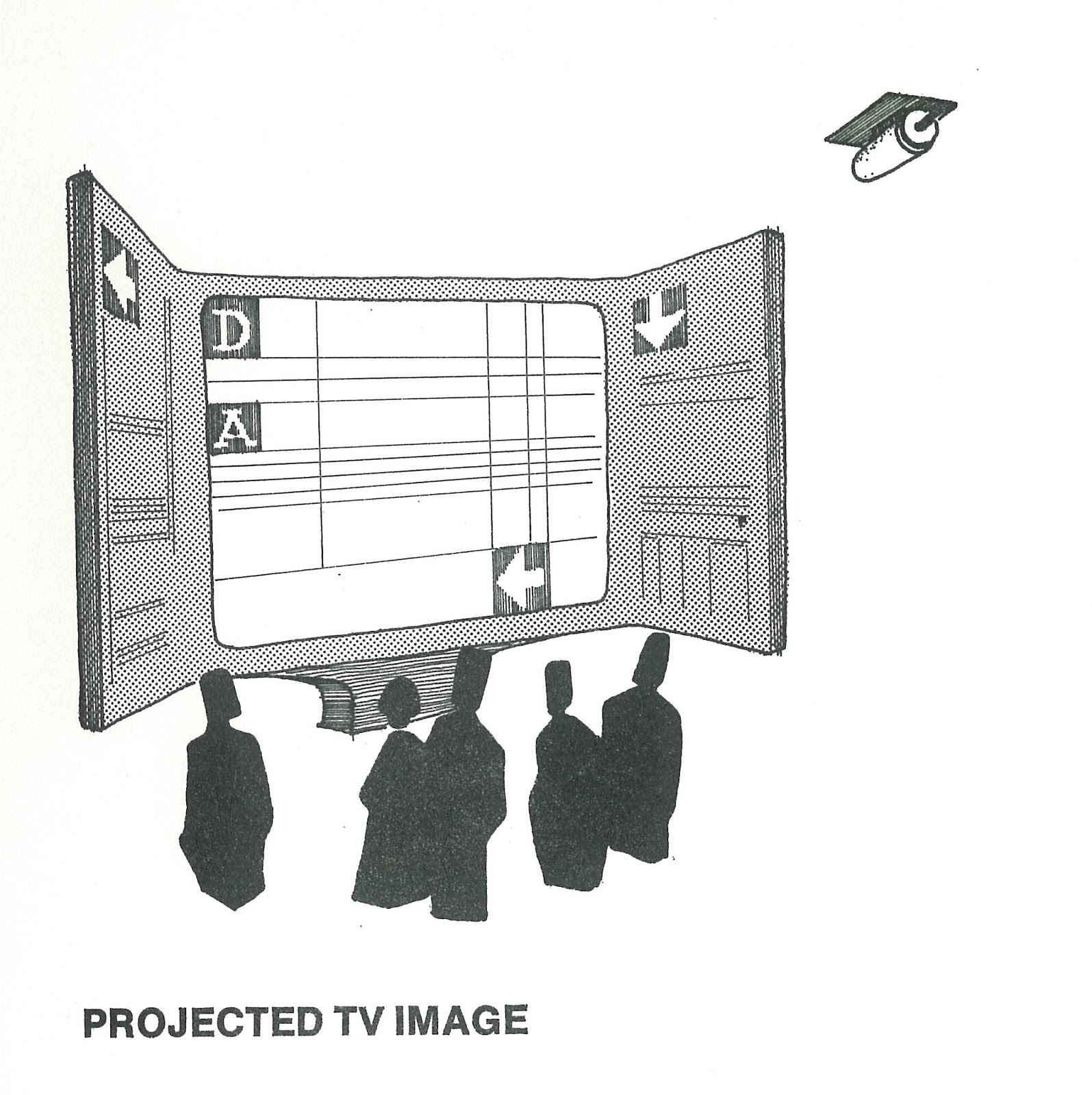

Pereira’s proposals also included the early adoption of human-architecture interfaces such as moving sidewalks, flight status change monitors, public address systems, and “pre-tuned receivers,” that bear an uncanny resemblance to today’s ubiquitous smart phones. The airport authority commissioners rejected or altered many of the proposed plans, and ultimately, the Theme Building became the remnant icon distilled from the plan for the central domed structure. Modernist Maverick presents elements of both the far-reaching and unrealized plans Pereira conceived for LAX, as well as elements that were built at the airport, and raises questions about the alternate futures that might have been had Pereira’s plans and designs been more fully realized.

Pereira’s creative and thoughtful capacity to imagine—which is not to say predict— the future of Southern California at the height of its post-WWII growth are why, in part, an exhibition presenting his work as an architect and planner is of interest to CFM readers, and to people interested in the histories of twentieth century design and architecture, generally. The exhibition and accompanying catalogue and documentary film attempt to raise questions as to why someone as prolific as Pereira is not better remembered today, and to ask how architecture and planning as exhibited subjects in museums can present histories and ideas of alternate futures—the futures that might have been.

I visited Colin in 2011, when the Nevada Museum of Art hosted To Live Forever: Egyptian Treasures from the Brooklyn Museum. NMA created additional interpretation for the touring show, that reflected the then-recent political revolution in Egypt. It included speculative musings from science fiction author & futurist Bruce Sterling, accompanied by an 80-foot panoramic mural depicting a possible future Egypt. As the exhibit catalog noted “In much the same way that the antiquities on display offer only traces of historical evidence helping us to understand Egypt’s past, Sterling’s contribution and the accompanying mural illustrates one of many possible outcomes for the future of this dynamic and rapidly-changing country.” I lovethe approach NMA is taking to the historical future and to future history. Can you share other examples of museums playing in the futurist realm? Please clue us in, using the comments section, below.

Elizabeth Merritt