Any experiment that overturns business as usual can give us a glimpse of alternate futures. Some of the most entrenched “usuals” in museums are related to authority and process: Who sets the agenda for what we do, and how? This week Divya Rao Heffley, program manager of the Hillman Photography Initiative at the Carnegie Museum of Art, relates how that project is turning some museum conventions upside down.

The Hillman Photography Initiative website |

The Carnegie Museum of Art launched the Hillman Photography Initiative earlier this year as a living laboratory for exploring the rapidly changing field of photography and its impact on the world.

|

| L to R: Hillman Photography Initiative “Agents” Alex Klein, Arthur Ou, and Marvin Heiferman meeting with Carnegie Museum of Art staff to discuss the current state and future of photography and to begin planning for the project. |

The intensive four-month planning process gathered five internationally-known experts (aka Agents) together in a far-ranging conversation about photography. The Agents are Tina Kukielski (our internal CMOA Agent and co-curator of the 2013 Carnegie International), Marvin Heiferman (independent curator and writer), Illah Nourbakhsh (professor of robotics and director of the CREATE Lab, Carnegie Mellon University), Alex Klein (the Dorothy and Stephen R. Weber Program Curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia), and Arthur Ou (assistant professor of photography at Parsons The New School for Design). We asked them to identify the most exciting issues and questions in field in which billions of images were shared daily and on a global basis. For teachers, what made their students sit up and listen? For curators, how did their research connect with the person on the street? For artists, how did the digital revolution affect their practice? What aspects of photography did the Agents discuss around the kitchen table with their partners, friends, and kids?

|

| This Picture explores what photographic images can say and do by tracking the responses and feedback a single image can trigger and generate. The public is invited to submit responses to a carefully selected photograph each month. Image: Marilyn Monroe during the filming of The Misfits, 1960 © Eve Arnold/Magnum Photos |

As a result of those incredibly stimulating conversations we realized that the most interesting aspect of photography today is how it travels. From creation through transmission, distribution, circulation, appropriation, even death, the photograph follows a lifecycle that can be physical or virtual (or both). The projects that emerged from these discussions—This Picture, The Invisible Photograph, The Sandbox, A People’s History of Pittsburgh, and Orphaned Images—all explore the concept of this lifecycle.

|

| A People’s History of Pittsburgh compiles family-owned, found, and anonymous photographs from the city’s residents to create an online archive that unearths and reconstructs narratives through the lives of Pittsburghers. Image: The Baron family’s Croatian tamburitza band, Braddock, PA, January 23, 1930, Submitted by Jennifer Baron. |

|

The Sandbox: At Play with the Photobook includes a temporary reading room and event space at the museum, with programming investigating the many ways that photobooks present and interpret images. Photographers Melissa Catanese and Ed Panar of Spaces Corners, a Pittsburgh bookshop specializing in photography books, staff the reading room.

|

The intricate set of online and onsite projects of the Initiative required us to create new ways of operating. Most of the Carnegie Museum of Art’s internal processes revolve around the development, approval, and implementation of exhibitions and events. Typically an exhibition is proposed by a curator and is reviewed and approved by an internal group of departmental directors. The Initiative was developed and implemented outside of that normal workflow. The point was to ask outside voices (the Agents) to propose the projects that the museum would then implement and build. This experiment challenged the museum to reexamine its own assumptions, benchmarks, and even its metrics of success.

|

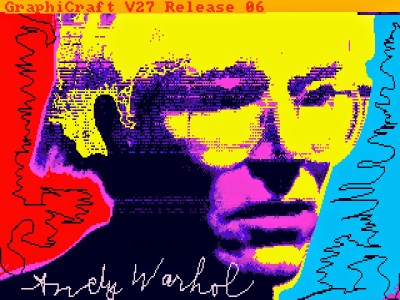

| Trapped: Andy Warhol’s Amiga Experiments (Part 2 of The Invisible Photograph documentary series) investigates how a team of computer scientists, archivists, artists, and curators teamed up to unearth Warhol’s lost digital works. Image: Andy Warhol, Andy1, 1985, digital image, The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; From disk 1998.3.2129.3.4 |

GAUGING SUCCESS

In fact, we realized that the process was so experimental that none of our standard benchmarking procedures would suffice as evaluation metrics. So we began inventing new benchmarks from scratch. Our director of education asked questions like, “How does being interested in what our visitors think change the museum?” And: “Does the Initiative change the way we establish online engagement with audiences in other exhibition or collection areas?” Our web and digital media manager got us thinking when he told us he could not only track how people were navigating or clicking through the website, but where they were coming from and how long they spent on any given page. Our director of publications ruminated on whether we could “see the Initiative as a model for developing standards for online writing for all museum projects, not only for content but also for tone and approach.” Our marketing team discussed extending audience engagement from the typical art scene to the sciences, social sciences, and technology. From a curatorial point of view, we’re just as interested in assessing the less tangible metrics of success, such as how the Initiative shapes ideas about photography locally and internationally.

Within days of launching the Initiative, we began gathering statistics to figure out what was going on. How many people were coming to our website and accessing our content? Were they engaging with our content? Did we have to shift our marketing strategies? The hierarchy of content on our website? The types of demographic content we were gathering at events?

|

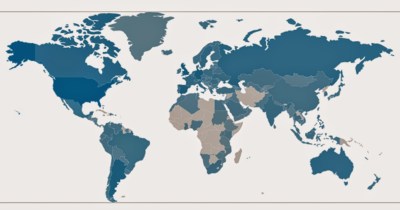

The first two installments of The Invisible Photograph documentary series (premiered online at

nowseethis.org) reached a large number of viewers worldwide despite being longer format films. |

Here are some findings from our first full month of evaluation:

- The Initiative’s web activity equaled the activity on all other museum sites combined, including main site, blogs, and microsites. In terms of web campaigns, nowseethis.org is on par with other high-profile web campaigns such as the 2013 Carnegie International.

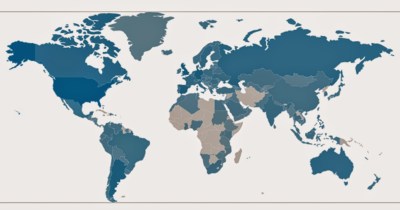

- We surpassed our wildest dreams in terms of reach for Part 1 and Part 2 of The Invisible Photograph, which achieved global viewership, reaching six continents. These two 20-minute videos had over 60,000 complete views and over 300,000 loads. This runs counter to the popular consensus that says shorter videos perform better and shows that there is significant appetite for more substantive content online.

- The earned media value for the Initiative in the first month alone was approximately $4 million. To put that in perspective, in all of 2013 our earned media was $8 million, which was itself a record year for us thanks to the 2013 Carnegie International.

From the beginning of our social media campaign on March 16, Initiative-related content more than tripled the museum’s reach of Facebook posts through user sharing and liking. We tracked a significant upward trend in people “liking” CMOA that corresponded to the launch of the Initiative. On Twitter, of the top 15 posts from the museum’s account @cmoa, more than half were HPI-related. These posts saw increased reach that was sometimes three to five times greater than the average museum tweet.

However, there was relatively modest onsite attendance for the Initiative’s related programs. We think this is in large part due to the fact that we did not prioritize onsite attendance when asking the Agents to propose projects. This has created tension with our institution’s larger mission to encourage onsite attendance, so we are trying some changes that might address this issue, such instituting a “pay what you can” price structure. We’re also discovering that creating an onsite to online connection, which is at the heart of the Initiative, is one of the harder goals to accomplish. One of the best suggestions from our last meeting is to use “onsite payoff” to encourage online submissions by printing the submissions, posting them in the gallery, and featuring them on our website. We think that such onsite payoff is one of the main reasons that Oh Snap: Your Take on Our Photographs, (another experimental museum project and an important precedent for the Initiative), was such a success last year.

What happens next is anyone’s guess. But one thing is for sure: the more experimental the process, the more progressive we need to be to evaluate the outcome. Because, as the old saying goes, if you don’t evaluate, you’ve already failed (or something like that). For any project that’s even remotely experimental, the need for unconventional thinking never ends.

For more information, read an expanded version of this post on the Hillman Photography Initiative’s blog.

Elizabeth Merritt