“To give real service you must add something which cannot be bought or measured with money, and that is sincerity and integrity.”—Douglas Adams

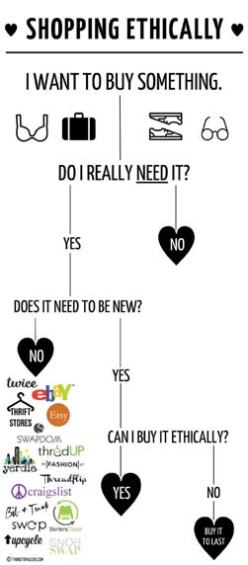

Increasingly the press and our peers remind us that each purchase we make and each bite we take has ripple effects on the world. The fact that, in this Internet age, we

could research and vet the entire life cycle of a product or service, creates an expectation that we should. And this, in turn, leads to increased demand for transparency and accountability in behavior, sourcing and production. United and empowered by the Internet and by social media, today’s consumers wield unprecedented power, and woe betides any company that crosses the invisible ethical line. And nonprofits, traditionally assumed to be on the side of angels, don’t get a free pass in this era of

soul-searching.

On April 24, 2013, a garment factory housed in the eight-story Rana Plaza collapsed in Bangladesh, killing 1,129 people and injuring over a thousand more. Echoing the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911 and its aftermath, this event triggered nationwide protests among workers and sparked global soul-searching over the role that consumers and the fashion industry play in creating exploitative, dangerous, low-wage jobs in the third world. The fashion industry is responding in a variety of ways, from startups emphasizing ethical sourcing and recycled materials and durable goods, to Vivienne Westwood, the progenitor of punk fashion and now a major force in fashion design, declaring “we might be able to save the world through fashion.”

line of clothing that is 100 percent compostable, and is

woven from low water-usage crops. Photo: Oliver Nanzig

Social justice concerns are becoming a mainstream part of retail branding, as 32 percent of Millennials have stopped buying from companies they feel fall short when it comes to ethics and social practice. Food has become an impossibly fraught ethical minefield. Eat beef and fuel global warming; eat quinoa and contribute to the collapse of traditional farming in Bolivia. Buy tomatoes in the winter and support slavery in Florida. Scientists are even creating yeast that synthesizes milk so we don’t have to exploit cows. Whole Foods, long dogged by its image as a purveyor of luxury foods to the elite (“Whole Paycheck”) is rebranding itself around values, positioning its choice of what to sell, and at what prices, as being about responsibility. “To us,” WF declares, “value is inseparable from values.”

These scruples apply not just to purchasing decisions, but to broader expectations of corporation citizenship. A recent survey of Millennials by Deloitte showed that a majority feel that business can do more to tackle resource scarcity, climate change and income inequality. Pay equity is ballooning into a huge issue, whether it focuses on providing a living wage or reining in CEO salaries. And ethics get personal when the public feels that a company has violated ethical norms regarding their personal data—see, for example, the firestorm when it was revealed that Facebook allowed researchers to tinker with users’ newsfeeds to see if they could manipulate their moods. Incidents like that pave the way for startups like Sgrouples and Ello that promise to provide “ethical social networking”—ad free and without the pervasive data collection and surveillance that characterize the big players in this field.

On August 13, 2014, the value of Sea World stock plunged 33 percent in one day after the company announced a 5 percent decrease in attendance and an 8 percent drop in revenue even as attendance at other attractions increased by 5 percent. PETA and other activists had been picketing Sea World for years, but the ethics of keeping whales in captivity was catapulted to national attention by the documentary film Black Fish. The accompanying storm of social media (hashtag #Blackfish) paved the way for a bill in California that would have banned killer whales in captivity. The bill didn’t pass, but Sea World’s reputation took a heavy economic hit. This demonstrates how ethical concerns that may have previously been confined to fringe groups can spread like wildfire via mainstream and social media either spontaneously or through orchestrated campaigns.

What This Means for Society

Our heightened attention to ethics is driven in part by emerging technologies. We didn’t worry about manipulating the genome of our food until we started doing so in the lab, rather than the old fashioned way. The current debates over net neutrality are as much about the ethics of equitable access to a resource that has become as basic as water or electricity, as it is about economics. We didn’t debate whether robots guided by artificial intelligence should be allowed to wage war on our behalf until we created functional prototypes that can do just that. As we gain the capacity to screen the genome of embryos, disability rights activists are arguing it is unethical to choose not to have a child with Down’s Syndrome, or dwarfism, or a host of other congenital “abnormalities,” tagging the practice as “the new eugenics.”

Corporations big and small are rethinking how to manage their reputations, realizing they can’t control their public image solely through advertising campaigns. When a single tweet, like #DeleteUber, can amplify to reach millions, individuals have the power to call companies on errant behavior. Social media specialists are on the front line of reputation management—navigating when to delete, respond to or simply endure critical comments. Many industries are proactively adopting Corporate Social Responsibility policies to selfregulate compliance with ethical norms (and fend off legislative oversight).

What This Means for Museums

Nonprofits aren’t exempt from the ethical lens being brought to bear on the world, and museums can’t take for granted that people think they are the good guys. Concerns about animal rights, for example, are triggered by various aspects of museums’ work. This past year an installation by artist Cai Guo-Qiang at the Aspen Art Museum triggered protests when he glued iPads displaying video of local ghost towns to the backs of three African tortoises. A museum spokesperson’s response (“It is not the Museum’s practice to censor artists”) didn’t quell concerns of people who felt the work of the artist was itself ethically questionable. Similar protests led to the cancellation ofan art project funded in collaboration with the University of Kansas’s Spencer Museum of Art, which would have ended with the slaughter of chickens to provoke debate about the ethics of food and farming. (#Irony.)

Ethical fastidiousness about respecting animal life can spiral to extremes (as in an essay in the New York Times advocating the extinction of all carnivorous species, and the firestorm of Internet hate unleashed on a researcher at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology who blogged about collecting a single Goliath birdeating spider). However, it manifests itself in more mainstream forums as well—see, for example, the recent spectacle of scientists scolding other scientists for killing animals as voucher specimens. Both the Boston Aquarium and the Georgia Aquarium have come under fire for their proposals to keep whales in captivity—in the eyes of the general public, the line dividing commercial aquariums/theme parks like Sea World from their nonprofit kin is already thin (if not invisible). It is imperative for both living and nonliving collections to set forth clear and compelling ethical rationales for the taking, and holding, of life.

Labor rights groups have staged repeated protests about the work conditions of migrant laborers building the Guggenheim’s branch in Abu Dhabi, orchestrating campaigns designed to influence the museum’s trustees and donors. This dramatizes museums’ need to examine not only their own practices, but those of their subcontractors and partners both at home and abroad.

While the laws regarding unpaid internships are quite clear for for-profit companies, nonprofits exist in a grey area “awaiting clarification” from the Wage and Hour division of the U.S. Department of Labor. However, unpaid internships are increasingly being cast as a moral issue for nonprofits. In the past two years, both the British Museum and the Serpentine Gallery have been subject to protests regarding their use (or proposed use) of unpaid labor. In a field that relies heavily on volunteers (a typical ratio being 6:1 unpaid:paid staff) the issue of distinguishing among various types of unpaid staff therefore becomes very fraught.

At the other end of the pay scale, there is also increasing concern in both the for-profit and nonprofit realms about the ethics of the ratio between a leader’s salary and that of the lowest-paid worker. In the past few years, janitorial and food service employees of the Smithsonian have repeatedly gone on strike, demanding a wage that would enable them to live in or around the nation’s capital. Last fall, as a union made the same demand of the U.K.’s National Trust, a spokesperson declaimed,

“These are the guardians of our national heritage, yet they are left to struggle on with wages from a bygone era.”

There is growing skepticism about the efficacy of the firewalls museums create between major donors or corporate sponsors and the museum’s research and interpretation. Last year, in conjunction with the People’s Climate March in New York City, the artists’ collaborative Not An Alternative debuted a pop-up, “the Natural History Museum,” at the Queens Museum. That project questions whether museums like the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) and the National Museum of Natural History have softened their message on climate change as a consequence of receiving significant gifts from billionaire David Koch (who also sits on the

board of AMNH). In the U.K., Liberate Tate has staged a series of interventions protesting the ties between cultural institutions and the oil industry.

Museum Examples

The Royal Museums Greenwich have committed to purchasing for their retail outlets only goods that have been produced under fair labor conditions and have been elected for minimal impact on climate change. Their publicly available commitment to values governing both labor and environmental standards is clear about the fact that this promise not only protects their brand and reputation, but adds to the perceived value of their offerings and builds “an Audience whichis interested in ethical, recycled, UK-made and hand-crafted product.”

In 2013, the Field Museum of Natural History hired Emily Graslie, a creator of the popular YouTube video series The Brain Scoop. In a time when, as noted above, natural history museums are subject to heightened scrutiny about killing animals, it is important to educate people about what research collections are and what they are for. Graslie helps the entire sector when she explains in a compelling, personally engaging way why a museum might want to skin a wolf or stick a pin in an insect.

Last year the Museum of Modern Art organized a panel on synthetic biology and design, “Synthetic Aesthetics: New Frontiers in Contemporary Design,” which explored the “notion that imagined realities might give birth to material realities imposes serious ethical questions on artists who use synthetic biologyin their work.” Museums can play a role in helping the public work through issues related to choices raised by emerging technologies. Art is an engaging and nonthreatening platform for asking questions like: Just because we can do something like manipulating our own DNA or bioengineering our environment, does that mean we should?

Museums Might Want to…

Review and revise their ethics statements to address emerging issues. Traditional areas of concern like conflict-of-interest and provenance research may need to be expanded to include sections on internships, privacy of digital data and the ethical provenance of art displayed in the museum. Policies on individualand corporate support may need to be updated and strengthened, and museums working in the global arena may want to take a proactive stance on ethical concerns related to that work.

Commit to ethical sourcing of inventory offered in the museum shop and food sold in the museum food services. (This has the added benefit of tying the retail aspects of the museum to the organization’s mission, and potentially folds retail into the overall interpretive framework.)

Review policies about endowment investing and corporate sponsorships. There is a national trend of universities and other nonprofits engaging in fossil fuel divestment. Union Seminary characterized the act of pulling their investment from fossil fuels as “a bid to atone for the ’sin’ of contributing to climate change.” Now might be a good time to discuss what investments are consonant or inconsistent with the museum’s mission and values.

Debate the pros and cons of having people on the board who publicly and professionally advance causes antithetical to the museum’s mission, whether that be science, sustainability or children’s health. As Chris Norris has pointed out on the Prerogative of Harlots blog, on one hand museums need to protect the trust the public places in our independence, on the other hand it may be “better to have [people with divergent views] at the table than to exclude them.”

Review the museum’s policies regarding compensation, and hold open and frank discussions about issues including unpaid internships, highest-to-lowest paid worker ratio and paying a living wage. Further Reading

Further Reading

The Ethical Trading Initiative promulgates the ETI Base Code, an internationally recognized code of labor practice founded on the conventions of the International Labour Organisation (ILO). “Adhering to this code helps improve working conditions in global supply chains.” http://www.ethicaltrade.org/eti-base-code

A Discussion Guide for Executives about Communications and Ethics. (PDF, 15 pp.) This guide from the Ethics Resource Center provides an introduction to the value of publicizing an organization’s commitment to ethics, strategies for making the public case for integrity and key messages for consumers. While designed for for-profit companies, it may be useful to nonprofit organizations as well. http://www.ethics.org/resource/building-corporate-reputation-integrity