According to the Floodsmart.gov website, coastal areas of the US account for more than half of the nation’s population and housing. This pattern is reflected the distribution of American museums as well. This being so, the rising sea levels and increased risk of severe storms that face our century is of critical importance to our field. In today’s post Sarah Sutton, principal of Sustainable Museums (@greenmuseum on Twitter) tells us about a recent conference that explored how historic preservation can adapt to the challenges of climate change.

What’s in your basement: the archives; a furnace? What about saltwater?

If you’re within two to seven feet of sea level today, then saltwater is in your future this century; if, like many early cultural sites, yours was built on land that was once wetland, then saltwater is already in your basement.

Imagine the sea regularly visiting your basement, cozying up to electrical panels, leaching brick foundations, or seeping into gift shop wares. Imagine if most high tides prevent visitor access and cost money for repairs. In New Hampshire at high tide saltwater sneaks into the basements of historic structures at Strawbery Banke Museum.

|

| Composite showing dry and flooding instances around 74 Bridge Street, Newport RI |

To keep ahead of Portsmouth’s sea level risestaff at Newport Restoration Foundation (NRF), has had to raise electrical outlets and panels, and move heating systems out of saltwater’s reach. Still, they have only bought a bit of time for 74 Bridge Street, once the home and workshop of well-known colonial cabinetmaker Christopher Townsend.

Pieter Roos, NRF’s executive director, knew he needed more than preservationists working on this, and that the field as a whole needed reinforcements. That’s why 350 state historic preservation officers, archaeologists, architects and engineers, designers, planners, historic site staff, community organizers and climate scientists gathered last month at NRF’s Keeping History Above Water Conference. We talked about the risks and damage seen worldwide, shared the current process of assessments and planning, and described a few implementation examples.

What to do? Document, protect, salvage, move, or abandon?

The field has dealt with water issues before: major hurricanes; whole communities lost to man-made dams, and rediscovered when water use drained the reservoir; and rivers changing course to reveal or cover burial places and villages. What’s different?

Hurricanes and storm surges were once occasional events; now they are frequent, severe, and wide-reaching. Ninety percent of heat trapped since 1955 has been absorbed by the seas. Warming water expands, creating higher high tides and greater storm surges. Then they come back before we’re ready.

Preservationists at Scotland’s Coastal Heritage at Risk (SCHARP) are inventorying sites, assessing their exposure to coastal erosion from sea level rise and increased storm activity. Citizen teams help identify and monitor sites; some they can rescue, others they cannot.

This led to discussions of triaging culture.

We heard how the National Park Service and Fernandina Beach, FL, both created internal metrics for calculating value and prioritizing sites for protection. And we heard how local communities, indigenous, ethnic, and otherwise, demand that their priorities be valued more than the calculations of outside professionals.

We viewed large-scale water barrier examples from London, Rotterdam, and Venice. We heard legitimate options for allowing buildings to float above high tides, or let water flow through lower levels. It requires heavy retrofitting to secure a building so it will float, harnessed to its poles, straight up and then back down again on its foundation. This suits simple structures under steady water rise. Few of our cultural sites comply, sitting as they often do near hard edges of urban waterfront settings, with century-by-century frame additions.

The alternative is permanently raising buildings: adding a lower level and lifting the structure above the flow. Domestic structures, okay; but raise a recorded historic structure? Change its relationship to its landscape and neighboring structures? Changes the nature of the building, and compromise the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Historic Structures? This was quite a conundrum for many, but not all, participants.

Howard Mansfield, in The Same Ax Twice (2001), explored how much change history can tolerate and still be history: if someone has an axe, made of a head and handle, and replaces the handle, and years later replaces the head, is it the same axe? Yes, he proposes, if the process of replacing the handle and head involved a true understanding the design, construction and use of the piece – the culture of it. SCHARP would agree. It is willing to change out place to keep structures. It may have no choice, as we may not: salvage archaeology often occurs right as sites cave to coastal erosion.

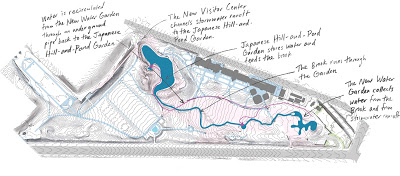

|

| Water recirculation project, Brooklyn Botanic Garden For more info see this post by S. Sutton |

The first-responders gathered in Portsmouth mostly avoided discussions of letting anything go, but offered few answers for saving – for now. I suspect the solutions lie somewhere in this list:

- Elevate mechanical hardware, ductwork, and power sources and outlets

- Learn wet and dry methods for protecting basements and first floors

- Adapt landscapes and buildings to cope

- Add a Secretary of the Interior’s Resilience Standard reflecting climate response for historic structures

- Add sites to state preservation plans to improve access to disaster funds

- Collaborate in communities and across the profession to create new, faster, and better responses to multiple threats to sites

- Strengthen citizen participation in identifying and recording endangered culture

- Include communities when deciding what to save

- Document the culture and architecture of climate response

And prepare to let go.

|

| Image by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates courtesy of Brooklyn Botanic Garden |

Recent article on coastline erosion due to climate change revealing critical needs for salvage archaeology: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2093905-race-to-save-hidden-treasures-under-threat-from-climate-change/