If you could chat with any historical figure, who would you choose? That question (or a variants such as “who would you invite to dinner”) is used as a pick-up line, debated on the web, even used in in job interviews. Now, thanks to advances in artificial intelligence, it’s close to becoming a practical question, one with disruptive implications for museums that strive to help audiences engage with the past. What if museums and archives could actually invite people to speak with the dead?

That thought was sparked by reading a recent Wired article in which James Vlahos recounts how he created a kind of digital immortality for his father in the form of a conversational artificial intelligence program. “Dadbot,” as he dubbed the project, draws on transcripts of interviews James recorded after his 80 year old father, John James Vlahos, was diagnosed with terminal cancer. In 2016, James began feeding that data into PullString, a program designed to create “conversational agents.” (James came across PullString when he was research a story for the New York Times about Hello Barbie, a “chatty, artificially intelligent update of the world’s most famous doll.”)

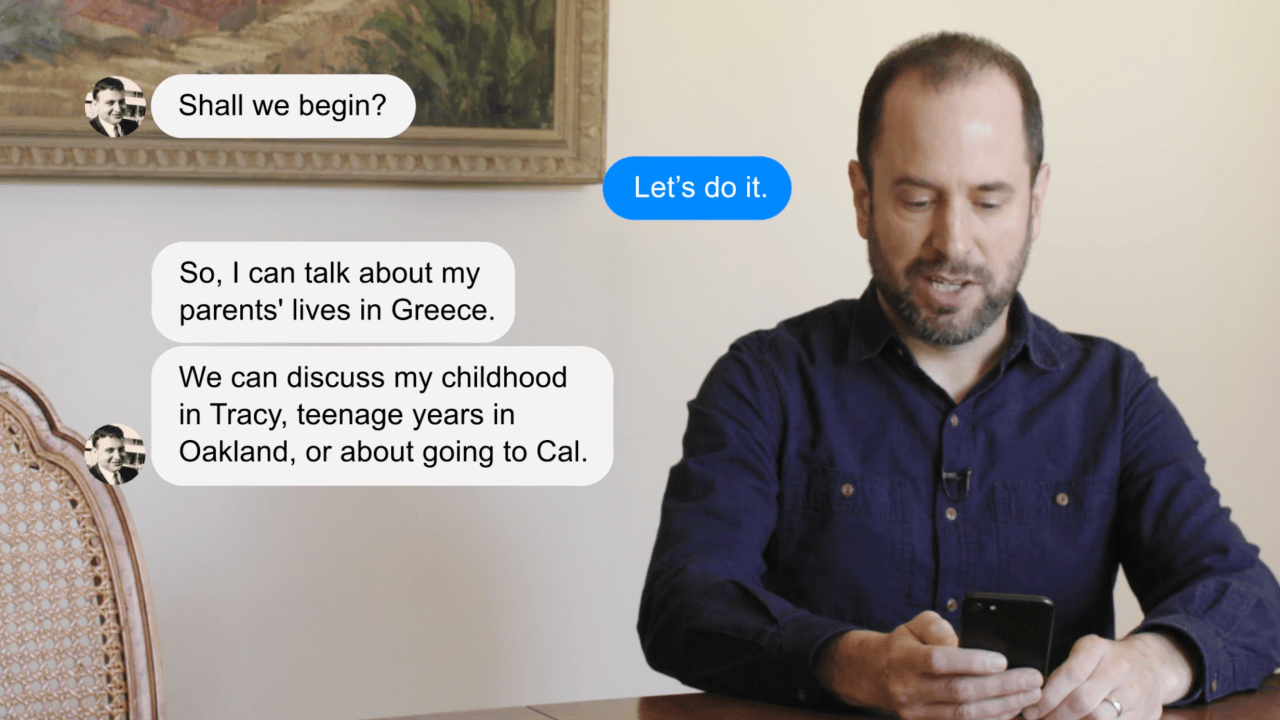

James spent hundreds of hours mining the recordings he’d made with his father (totaling 91,970 words) to create Dadbot. At first the chatbot could only converse via text messages. Later he used PullString options that let Dadbot talk out loud via Amazon’s Alexa device, and to embed audio files of his father singing or telling stories into the text message threads. Here’s a short video showing Dadbot at work:

Dadbot is about more than content—it’s about capturing some element of personality. In the article, James says “I don’t want it to only represent who my father is. The bot should showcase how he is as well. It should portray his manner (warm and self-effacing), outlook (mostly positive with bouts of gloominess), and personality (erudite, logical, and above all, humorous).”

When he proposed the Dadbot project to his parents, James explained that his motivation was to share his father’s life story in a dynamic way. His father, while not overly impressed, gave his approval, noting that he is comforted by the thought of Dadbot sharing his memories and stories with others, “My family, particularly. And the grandkids, who won’t know any of this stuff.”

While James created Dadbot to fill a personal need, I see the potential for museums to fill a public need by using conversational AI to bring history to life in a dynamic, engaging manner. I’m not the first to have that thought: James quotes PullString’s CEO, Oren Jacob as saying “I want to create technology that allows people to have conversations with characters who don’t exist in the physical world—because they’re fictional, like Buzz Lightyear, or because they’re dead, like Martin Luther King.”

Chatbots of historical figures, primed by published writings, archives and oral histories could engage with visitors inside the museum, and reach outside the museum to put history in the hands anyone who owns a smart phone. You could even deliver this kind of conversation AI via a robot, though until we get better at emulating human faces, that kind of embodiment is likely to tumble into the “uncanny valley” of looking just human enough to be creepy. (See, for example, this video in which the disembodied head of robot Bina 48 chats with the person her AI is designed to emulate.)

There are a number of compelling projects that use social media to bring historical records to life. From 2014- 2016, Cool Antarctica tweeted entries from the record of Ernest Shackleton’s expedition on the Endurance, transposed 100 years into the future. A coalition of organizations in Leicester, UK—Including the Imperial War Museum—are using the blog Captain J.D. Hills Letters from the Front to publish the letters of this WWI soldier 100 years to the day after they were written. These projects bring history to life by injecting individual voices into social feeds. Historical chatbots could turn this one-way push of content into a two-way conversation.

Are there potential downsides? Sure. For one thing, museums need to work through issues of consent. James sought his family’s permission before building Dadbot. In the future, will museums collecting oral histories routinely seek permission to adapt this content into an AI versions of the interviewee? What about the ethics of using AI to give voice to people who are already deceased—should their families be consulted first? Are figures from the distant past fair game?

I suppose that when AI become sufficiently advanced, an historical chatbot might be a bit tooconvincing, leading users to forget they are interacting with an algorithmic emulation of what the real person might have thought, or said. Then again, immersive historic sites such as Colonial Williamsburg already face that danger. By complying with some basic modern standards of sanitation, do they leave visitors with a “sanitized” understanding of what it was like to live in the colonial era?

James, for one, thinks we will have to tackle the ethical and practical challenges presented by advanced AI, predicting that the bot of the future will be able to not only reproduce what people actually said, but “generate new utterances,” and be emotionally perceptive and responsive in a conversation.

So, maybe I will get to chat with Charles Darwin after all.

To learn more about how artificial intelligence may shape the future of museums, watch the recording of this webinar presented by Blackbaud, with special guests Jeffrey Inscho of The Studio at Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh and Blackbaud’s Anthony Tomaino.

Hi There, Missed the opportunity to participate in this today. Is it recorded anywhere? –larissa hansen hallgren, larissahallgren@gmail.com

Hi Larissa! Blackbaud recorded the webinar and will be sharing a link. I will post it to CFM's social media: Twitter @futureofmuseums, and Facebook futureofmuseums.

Here is a link to the recording of the Blackbaud webinar on museums and AI, Larissa: https://event.on24.com/wcc/r/1450193/2B20BA44D9EC335E2E00C78ACF92F4BA

I feel saietfsid after reading that one.