This is one of the five trends from the 2019 TrendsWatch. Click here to read more about the full report.

“You call this progress, because you have motor cars and telephones and flying machines and a thousand potions to make you smell better? And people sleeping on the streets?” –Howard Zinn

Housing insecurity is a classic “wicked problem”—a significant social or cultural challenge that’s difficult to solve for multiple reasons: We have incomplete and contradictory knowledge about effective ways to tackle the housing crisis. The potential solutions require buy-in from many players, including voters, policymakers, funders, and corporations. Housing insecurity imposes an enormous economic burden on individuals and society. And it is intertwined with other critical problems including health, education, employment, and social and economic mobility. Housing security is both a symptom and a cause of the deepening inequality of wealth, opportunity, and access that characterizes the start of the 21st century, and solving these problems will require all actors—government, industry, nonprofits, and philanthropy—to rethink their roles and responsibilities. How can cultural nonprofits play a bigger role in finding a solution? And while society collectively works to solve this wicked problem, how can cultural nonprofits ensure that people experiencing housing insecurity can exercise their right to take part in cultural life?

Description of the Trend

International law recognizes adequate housing as a fundamental human right and obligates governments to establish legislation, funding, and policies that prevent homelessness, prohibit forced evictions, address discrimination, protect the most vulnerable and marginalized groups, and guarantee that everyone’s housing is adequate. Despite this consensus, over 20 percent of the world’s population (1.6 billion people) lacks secure housing, and almost 2 percent (over 150 million people) are homeless. Without secure housing, many people are unable to exercise many other basic rights such as voting, or access health care and social services. Globally, homelessness has spiked as migrants and refugees flee war, economic crises, and climate displacement.

Even in wealthy, stable nations such as the United States and the United Kingdom, housing insecurity is rising in tandem with wealth inequality. It is darkly ironic that the 2008 mortgage loan crisis, which was based on the exploitation of the American dream of homeownership, has made owning a home, and the attendant promise of economic mobility and stability, even harder to attain. The controls placed on mortgages and lending in the wake of the crisis have both increased the number of renters and driven up the cost of being a renter. By 2015, 38 percent of US renter households were “rent burdened,” spending 30 percent or more of their pretax income on housing. Seventeen percent of such households spend over half of their income on rent. And as they spend more of their income on housing, these families have less to spend on meeting other needs, putting them at risk of economic instability, food insecurity, and poor health.

At the extreme end of housing insecurity lies homelessness. In 2017, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development documented over a half million people living as sheltered or unsheltered homeless, an increase of almost 1 percent from the year before. Following a decade of slow decline, this statistic may not seem alarming, but it masks a number of local crises. Homelessness in major cities rose by 5 percent last year and states such as North Dakota, California, New Mexico, and Vermont saw big jumps. Over the past 10 years, the number of homeless children has increased by almost 1 million. In New Zealand, nearly 1 percent of the population lives on the streets or in shelters, while in the United Kingdom the number of unsheltered homeless (people “sleeping rough”) has increased over 169 percent in the past eight years.

Homelessness and housing insecurity are not purely urban issues—they are hidden facets of rural poverty as well. Rural areas overall have higher rates of poverty, with little public transportation, making it more difficult for people without housing to access support services. About 40 percent of housing on Native American reservations is classified as substandard, and the Urban Institute estimates that 4 to 7 percent of people who identify as Native American or Alaskan Native would be homeless if relatives did not take them in.

Over a quarter of the sheltered homeless population in the US suffers from a serious mental illness, and absent an affordable, accessible system of treatment, the criminal justice system often fills the gap. In addition to the fact that unsheltered people are often jailed for behavior arising from untreated psychiatric conditions, there has been a dramatic increase in the last 10 years of local ordinances that effectively criminalize homelessness, making it illegal to sleep or camp in public places, live in a vehicle, loiter, panhandle, or even sit or lie down in some public areas. More cities are making it illegal to hand out food to the homeless, clearing homeless encampments, discarding people’s possessions (which may include ID, legal documents, and medication), and even deploying security robots to deter people from setting up tent cities.

Popular perception often holds that people who lack stable housing have somehow brought it on themselves—if they only got a job or an education, they could “pull themselves up by their bootstraps.” In fact, the National Low Income Housing Coalition hasn’t found a single state, metropolitan area, or county in the United States where someone who works 40 hours a week at federal minimum wage can afford a two-bedroom home at fair market rent. In only 22 counties (out of 3,000 nationwide) can such a worker afford even a one-bedroom home at fair market rent. In a time when having a college degree is a functional prerequisite for economic and social advancement, homelessness and housing insecurity also handicap people seeking to improve their lives through higher education. Nearly half of students at two-year community colleges and over a third attending four-year colleges experienced some degree of housing insecurity during the past year, while 12 and 9 percent, respectively, experienced homelessness.

What This Means for Society

Homelessness and housing insecurity are part of the spiraling feedback loop driving inequality in society. These problems disproportionately affect populations that are already disadvantaged, including the disabled, the formerly incarcerated, the elderly, people of color, and non-gender-conforming individuals. They reflect, perpetuate, and amplify a national legacy of bias in housing, home ownership, and incarceration. To break with this legacy, we need to redefine our obligations to each other as fellow members of society. Will we continue to stigmatize the unfortunate as “other,” or recognize them as fellow human beings, subject to our basic mutual obligations within a community?

explored the hidden causes of homelessness and the science behind how people become dehumanized. Credit: Joel Fildes.

Many government and private programs that provide housing take a judgmental approach that requires people to get a job, seek help for substance abuse, or clear other hurdles before they are eligible for assistance. By contrast, the growing national Housing First movement advocates for providing basic necessities like food and shelter before expecting people to demonstrate their worthiness for assistance by getting a job or seeking treatment for substance abuse. This approach is difficult and at times controversial, as it depends on a supply of affordable housing stock and requires long-term support services that are not always available.

In our increasingly urban world, we embody our social values in the cities we create. The rise in “unkind architecture,” designed to make it harder for homeless people to find a place to rest and sleep, expresses a “Not in My Back Yard” attitude that excludes and marginalizes the homeless rather than solving the problem. By contrast, some cities (e.g., Oakland, San Diego, Portland, Seattle) have taken a different approach—providing sanctioned homeless camps with prefab sheds, 24-hour security, and social services, or modifying zoning regulations to legalize “alternative architecture” such as affordable tiny houses in alleys, on parking lots, or on vacant land. An experiment in Detroit enables residents to rent-to-own micro houses for $1 per square foot per month, providing a path to home ownership without a mortgage.

At the national and state level, policymakers are struggling to find legislative and legal solutions. California State Sen. Scott Wiener (D) has proposed a policy that would give every homeless person in the state the right to a bed year-round. At the national level, the Department of Justice filed a brief in 2015 arguing that it is unconstitutional to make it a crime for homeless people to sleep in public places. In Seattle and San Francisco, legislators have floated proposals to tax local tech companies that many blame for driving up housing prices by creating an influx of highly paid workers. The tax revenue would fund supportive housing, shelters, mental health services, and rental assistance.

Governments, companies, and individual activists are exploring how to harness digital tools to tackle housing insecurity. New York City, which counts more homeless people than any other US city, has introduced StreetSmart, a system that compiles and shares data on this population daily, enabling city agencies and nonprofit service providers to coordinate their work.

On the other hand, our digital age creates challenges for the homeless. With the rise of digital payments, for example, fewer people are carrying cash, and small donations to people on the street are in decline. In response, Amsterdam produced a winter jacket for homeless citizens that is rigged to accept wireless debit donations, channeling the funds to meals, housing, or bathing facilities. There is also a risk that the digital divide can disadvantage this vulnerable population. Social media platforms can be powerful tools for connecting people to social services, but a 2011 study showed only 62 percent of homeless teens had cell phones. While tech can sometimes be used to help the homeless—a recent experiment in Cairns, Australia, coopted footage from CCTV surveillance cameras to coordinate efforts to provide health and housing services—surveillance is more commonly deployed to police public space and remove the homeless from public view.

What This Means for Museums

Society often treats food, safety, and shelter as needs that must be met before people can satisfy “higher” needs, including self-actualization through arts, history, and culture. The UN Declaration of Human Rights challenges this assumption, giving equal weight to the right to housing (article 25) and “the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits” (article 27). If museums are to be public resources that are truly accessible to all, they need to disrupt Maslow’s hierarchy of needs—a five-tier, pyramid-shaped model that places people’s physiological needs at the bottom and self-actualization at the top. Museums need to serve not just people who have reached the “tip of the pyramid” but those who are not yet adequately housed, fed, or safe.

Museums aspiring to serve the homeless population can learn from their library cousins. People experiencing homelessness often patronize libraries, which they see as safe and welcoming places. In 1996, the American Library Association formed the Hunger, Homelessness, and Poverty Task Force, and there are numerous examples of libraries implementing its recommendations. The San Francisco Public Library, the first library in the country to hire a full-time social worker, now has seven health and safety advocates on staff, all of whom were once homeless themselves. Museums are not commonly treated as safe spaces by large portions of their communities, including people experiencing homelessness and housing insecurity. How can museums become more welcoming and inclusive?

The museum sector often thinks about equity in terms of access to exhibits and educational programs. There is now a robust and growing movement to make museums’ digital assets, including documentation and images of collections, open and accessible. But museums also control immensely powerful intangible assets: reputation, reach, and networks of influence. Some museums are beginning to map these assets against community needs, exploring how they can be deployed to help individuals improve their own lives, whether by creating an economic market for the work of indigenous craftspeople (the International Folk Art Museum in Santa Fe), or providing local teens with training and credentials to enter the fashion industry (Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt Museum’s Design Prep Academy).

Gentrification is one factor driving up housing costs and displacing community residents. Museums have been tagged by some as agents of gentrification—though a growing body of research (for example, a 2016 study published in Urban Studies) suggests that traditional arts establishments (like museums) tend to follow, rather than cause, gentrification. That said, museums are influential players in the urban landscape, and need to be mindful of how they contribute to the creation or solution of wicked problems like housing insecurity.

Museums Might Want to…

- Educate themselves and their visitors about the state of homelessness and housing insecurity in their community.

- Find ways to serve families and individuals experiencing homelessness and housing insecurity by making them feel welcome at the museum, and/or by taking the museum to them. By prioritizing social inclusion, museums can combat the isolation that often results from homelessness, and help people build social networks and foster self-worth.

- Create a code of conduct that clearly outlines both the museum’s commitment to accessibility and the behavior expected of (any) patron. Train front-line staff to ensure they are ready to welcome all visitors and equipped to appropriately navigate any challenges that arise.

- Following the lead of the San Francisco Public Library and other libraries, hire staff who have experienced homelessness themselves in order to encourage a welcoming use of the space and foster mutually beneficial relationships with the local homeless community.

- When planning an expansion or new building, work with neighboring constituencies to create a Community Benefits Agreement that specifies how the museum will contribute to the wellbeing of the community. Efforts may include paying a living wage, hiring locally, or providing space that meets community needs.

- Give people who have experienced homelessness voice and agency to tell their own stories.

- Document and share best practices with other museums engaged in this work.

The Museum of Street Culture employs clients of the Stewpot, an organization providing a safe haven for homeless and at-risk individuals of Dallas, as docents and tour guides. Photograph by Alan Govenar, courtesy of Documentary Arts.

Museum Examples

- In 2018, several museum exhibits explored homelessness and housing insecurity. “Evicted,” a collaboration between the National Building Museum and Princeton University sociologist Matthew Desmond, helped visitors explore the world of low-income renter eviction. “Shelter: Crafting a Safe Home,” organized by the Society for Contemporary Craft, Pittsburgh, invited 14 artists to explore the concept of shelter as a basic human right.

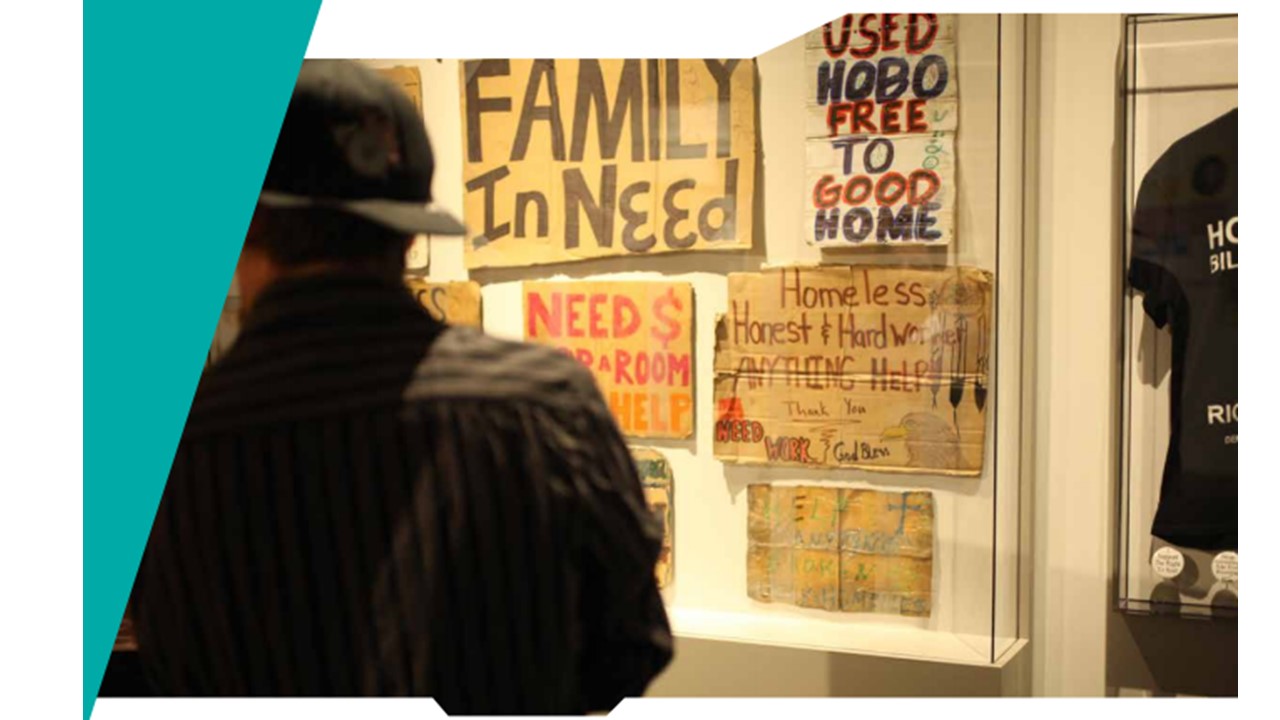

- Museums organizing such exhibits have invited people experiencing homelessness to tell their own stories. In the Portland Art Museum’s “One Step Away,” which focused on local housing insecurity, participant storytellers directed the development of the exhibition. The National Museum Cardiff’s “Who Decides?” (2017) was curated by people who have experienced homelessness. History Colorado included community members, including some experiencing homelessness, in the planning committee for “Searching for Home” (2016). The Museum of Street Culture recruits clients of the Stewpot, an organization providing a safe haven for homeless and at-risk individuals of Dallas, to serve as docents and tour guides.

- After several years of staging temporary installations around Chicago, in 2019 the National Public Housing Museum will reopen in the last remaining building of Chicago’s oldest federal housing project—the Jane Addams Homes. The museum is dedicated to presenting the ambitions and failures of public housing in the United States, preserving and presenting the stories of past residents of the project, and empowering current residents of nearby public housing. The museum’s Entrepreneurship Hub serves as a business incubator for public housing residents, providing business classes, pro bono advisory services, and a resident-owned cooperative store.

- In the UK, the Museum of Homelessness (which does not itself have a permanent home as of yet) “collects and shares the art, histories, and culture of homelessness and housing to change society for the better…[and] make the invisible visible through research, events, and exhibitions.” In 2017, they partnered with the Tate Modern to present “State of the Nation,” an installation/report exploring “what is happening in hostels, day centers, social housing, on the streets and in people’s hearts, minds and lives.” In 2018, the museum acted as pro bono producer for David Tovey’s immersive opera Man on a Bench, which “questions stereotypes about people who’ve been homeless and shows the beauty of second chances.”

the life of Erin Blackwell Charles (a.k.a. Tiny). Photograph by Alan Govenar, courtesy of Documentary Arts.

Further Reading

The Right to Adequate Housing. Human Rights Fact Sheet No. 21/Revision 1, Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. This publication explains the right to adequate housing, illustrates what it means for specific individuals and groups, and reviews governments’ related obligations. It also provides an overview of national, regional, and international accountability and monitoring mechanisms. Available at ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/FS21_rev_1_Housing_en.pdf.

“A Review of Arts and Homelessness in North America,” With One Voice: Connecting Arts and Homelessness Worldwide (2017). This review charts the state of homelessness in a number of cities, summarizes what those connected to arts and homelessness feel they require to continue their work, and offers some recommendations for meeting those needs. Available at with-one-voice.com/north-america-country-review.

See also their “Jigsaw of Homeless Support,” making the case that the arts should be available to people experiencing homelessness alongside other services from day one: with-one-voice.com/jigsaw-homeless-support.

WebJunction: The Learning Place for Libraries hosts an extensive list of resources on serving people experiencing homelessness that can be of assistance to museums. Includes links to the American Library Association’s Hunger, Homelessness, and Poverty Task Force resources, and a variety of online webinars and courses. Available at webjunction.org/news/webjunction/resources-libraries-and-homelessness.html.