The Black Rock Historical Society (BRHS) is a volunteer organization on the west side of Buffalo, NY, formed in 2013 around the two-hundredth anniversary of the War of 1812 and chartered with the New York State Education Department in 2019. Situated on the Niagara River and Erie Canal, the museum works to preserve the history of four geographic neighborhoods: Grant Amherst, Black Rock, Riverside, and West Hertel. These neighborhoods have a history of diversity that continues today, with newly arrived immigrants and refugees settling in and contributing to regrowth. These areas were originally inhabited by Native Americans, before settlers came from Germany, Poland, Ireland, and other European countries and formed tight-knit communities around their cultures, religions, and ethnicities.

The history of the Seneca and other first people is an important chapter in the story of Black Rock. We recognize our role in telling this story to the new settlers of Black Rock and preserving the history of the Seneca people who still live here. Our board includes founding member Doreen DeBoth, an artist and gallery owner from the Mohawks of Kahnawa:ke in Quebec, and William Butler, the former Indian Nations Liaison for the Buffalo District of the US Army Corps of Engineers. Both bring a wealth of experience and knowledge to this responsibility.

History of an island’s name

Though French explorers named the island separating the Niagara River and the Black Rock Canal “Squaw Island” in 1679, the Seneca Nation of Indians knew it as De-dyo-we-no-guh-doh, or Divided Island, because it was divided by a marsh creek called Smuggler’s Run. The Seneca Nation presented the island to agent and interpreter Captain Jasper Parish in 1798, as a gift in acknowledgment of his services on their behalf. It later became a strategic location during the War of 1812 for shipbuilding, troop landings, and departures. It continued to be known as Squaw Island from 1679 until 2015.

The road to change through education

In 2015, the Seneca Nation of New York State petitioned the City of Buffalo to change the name of the island, on the grounds that it was racist and derogatory toward Native American women. Elected officials then voted unanimously to change the island’s name to Ga’ni:go:yoh, or Unity Island. The City of Buffalo held a ceremony officially changing the name in 2015. At that point, the city abruptly removed a historical marker at the entrance to the island identifying it by its former name and moved it into storage. The BRHS asked to have it for the museum’s collection, which the city granted. As we pondered the best way to document the shameful history behind the name and at the same time to atone for it, we reached a decision. We began a fundraising effort for a new marker. Our state and local elected officials contributed, but then a dilemma presented itself: How could we best engage the Seneca Nation in a partnership with the BRHS and continue to develop a relationship that would be mutually beneficial?

The BRHS believed that the best way would be through an educational information exchange with the Seneca Nation based around the offensive historical marker. In the fall of 2016, we extended an invitation for a Seneca representative to speak at the museum’s weekly speaker series. The topic was “How derogatory terminology can be devastating to whole nations of people.” Rick Jemison, Councilor of the Seneca Nation, presented before a packed audience at the museum. For his talk, he chose to showcase beautiful beadwork artifacts, including wampum, and explain how they symbolized unity among different peoples, as handed down in Seneca teachings. The designs of purple and white shell beads on the wampum belts, for instance, recorded the laws of the Confederacy, oral tradition used for ceremonies, and important political interactions between Native nations, and later between the Confederacy and Europeans.

Mr. Jemison went on to explain that the Seneca Nation has the highest regard for women, as they are the lineal descent of the people of the Five Nations. According to the Great Law of the Five Nations, Native women owned the land and the soil. They had the power to own councils, depose chiefs, and make or stop war. However, their status was not accepted by Euro-American males, who refused to deal with Native women as leaders. They viewed Native women as slaves and used disrespectful racist slurs to describe them. Mr. Jemison stated that “squaw” was a racist slur used against Native women to stereotype them as a group. The use perpetuated a negative inference of Native women. For that reason, he said, the island’s old name was insensitive and outdated, and needed to be changed to correct an injustice too long inflicted upon Native women.

Mr. Jemison’s talk drew Seneca Nation members who had come to the museum for the first time. To complement his message and celebrate the national Native American Heritage month, a Native American history exhibit was on display at the museum. He previewed the display and discussed with the staff what visitors should take away about stereotyping of Indians (Hollywood portrayals, in advertising, and in children’s toys). The display included both positive and negative aspects of how Native Americans were treated and depicted in history. He said that history should be told so that lessons can be learned from it.

Funding the project

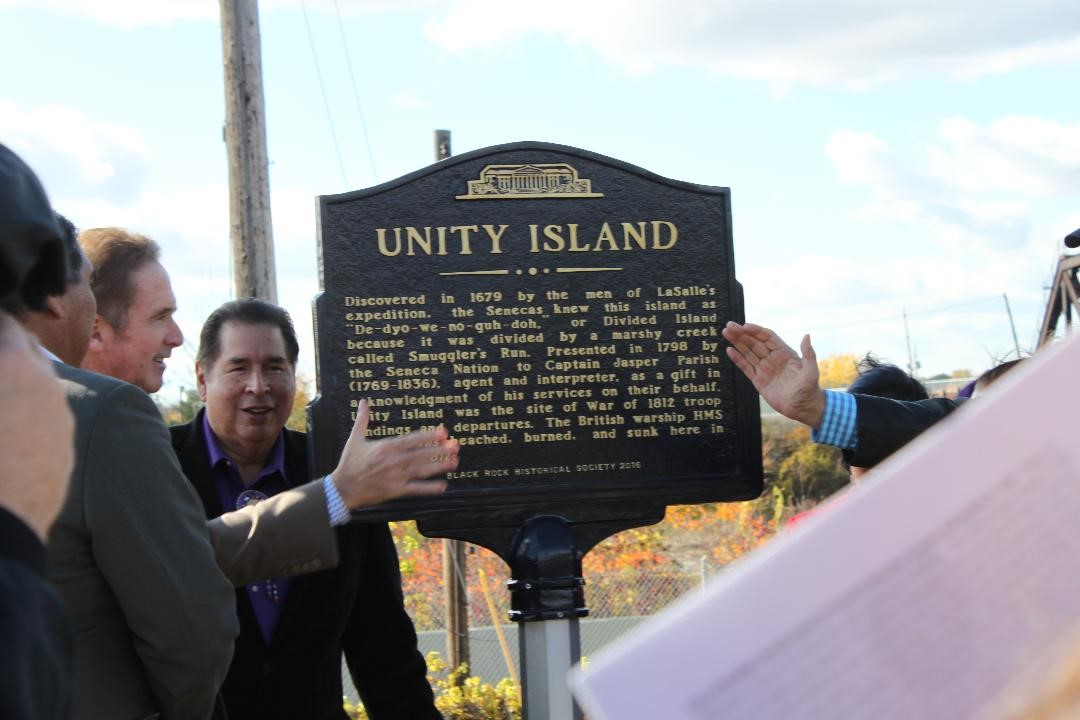

The BRHS asked the Seneca Nation if they would be interested in helping to fund the new historical marker for the island, thinking that funding would come from the Seneca’s gambling casino interests. Instead, to our surprise, they conducted a door-to-door fundraising effort on the Seneca Indian reservation and raised 500 dollars. This donation proved how vital it was to change the offensive marker. With the combination of these funds and those from elected officials, a new marker was ordered and installed at Unity Island. To celebrate the installation, we held a ceremony with Seneca leadership, elected officials, the Black Rock Historical Society, and members of the Seneca community in attendance. Outgoing Seneca Nation President Maurice John, standing alongside newly elected Seneca President Todd, spoke about the power of collaboration and the importance to the Seneca community of removing language biased against Native women. They thanked the elected officials for helping to fund the new marker and the BRHS for making it all happen. To show their appreciation, the Seneca community brought strawberry water to share with all the participants. We learned that strawberry water is symbolic of a celebration when people come together to honor, acknowledge, and give thanks to the environment for nature’s gifts. We then realized the significance of our actions and how it had come to a successful and valuable conclusion.

The future

We made the hard decision to have the original historical marker mounted and put on display at the museum with a plaque describing how the name Squaw Island was a shameful part of history. It will tell the story of how the BRHS, in collaboration with the Seneca community, changed the marker to its new name and thus created new history.

The BRHS has since been invited to several Native events in the area, including powwows and grand openings of significant community buildings. We have invited the Seneca Nation to our events, and will include another Native speaker in this year’s speaker series. The museum continues to celebrate Native American Heritage month with displays and actively seeks artifacts to add to its collection.

—

Written with contributions from Rick Jemison, Seneca Nation Planning Department; and William Butler, Board Member, Black Rock Historical Society.

About the author:

Michele Ann Graves is the Exhibits/Education Coordinator for the Black Rock Historical Society. She is also Community Relations Consultant for the Drug Free Communities Grant at the Center for Health and Social Research, SUNY College at Buffalo (Buffalo State), and retired as the Community Liaison for the Buffalo Police Department. She is a board member at NeighborWorks America, Grant Amherst Business Association, Member Forest District Civic Association, and the West Side Youth Development Coalition, SUNY Buffalo. She has authored publications for the Buffalo Police Department, Buffalo State College, The International Association of Chiefs of Police, The United States Justice Department, the Black Rock Historical Society, and for various community and business associations.

Growing up in Buffalo it amazed me how little of its rich history I was ignorant of.Its great to know there are people like your society that care enough to research all that you have to enlighten the rest of us who would never have known. Great article !