Museum studies graduate students co-curate a feminist art exhibition to test assumptions on ideal approaches to inclusion.

This article originally appeared in the March/April 2020 issue of Museum magazine, a benefit of AAM membership.

Across the United States, a wave of feminist exhibitions and programs are responding to the current political climate and gender and racial inequities and violence. Drawing from the #MeToo movement, LGBTQ+ advocacy, Black and Brown Lives Matter, and Decolonize This Place, museums and alliances like the Feminist Art Coalition are bringing activism into the exhibition space.

Given the multiplicity of definitions of feminism, the negotiations of our own identities, as well as the dynamics of our respective institutions, what are the challenges of such projects? What can we teach emerging museum professionals about best practices in inclusion?

In my role as a professor of art history and director of the Museum Studies M.A. program at the University of San Francisco (USF), I taught the annual curatorial practicum course in the fall of 2019. Along with 13 graduate students, I co-curated an exhibition focused on feminist art. “Emboldened, Embodied,” held at Thacher Gallery, USF, November 21, 2019–February 16, 2020, featured seven San Francisco Bay Area artists.

In collaboration with Thacher Gallery colleagues, Director Glori Simmons and Gallery Manager Nell Herbert, our goal was to teach students the nuts and bolts of curatorial practice in 14 weeks. How could I expose the class to theoretical approaches to feminist art, and the challenges in presenting it, while empowering these emerging museum professionals to promote equality by creating exhibition spaces and programming that is welcoming of all genders, sexualities, races, ethnicities, classes, ages, and abilities? In essence, how could I practice what I preach?

The Initial Groundwork

To begin, it was essential to examine my own identity, privileges, and motivations. As a white, cis-gendered, heterosexual woman, I entered the field of feminist art history in the 1990s at about the time legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” to address bias and violence against black women in the United States. In her article “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex” (1989), Crenshaw described how the interaction of race and gender was previously unaccounted for in feminist theory and antiracist policies and laws. Today, the term “intersectionality” is often used without crediting its historical origins in black feminism.

Feminist thought and practice have evolved in the past three decades to include a diverse range of perspectives and approaches to the questioning of power and bias. I was inspired to understand recent shifts toward intersectional feminism as they relate to Crenshaw’s work. In titling the show “Emboldened, Embodied,” I aimed to connote empowerment, a political call to action, and a celebration of the lived experiences of all who have been historically silenced or omitted from dominant narratives of art, history, and culture.

Given our unusually tight planning schedule, I identified and reached out to the artists before the course began. Thacher Gallery promotes the work of California artists and collectors whose works resonate with issues of social justice, in alignment with USF’s Jesuit Catholic mission. I sought to present diverse voices that would reflect the shifting approaches in feminist art.

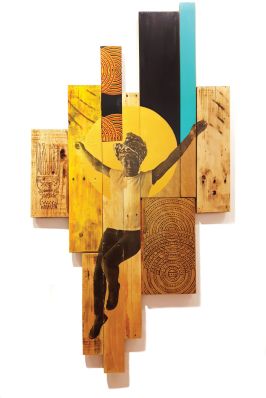

The final list included seven artists working in diverse media spanning four decades: Kim Anno, Lenore Chinn, Angela Hennessy, Yolanda López, Jessica Sabogal, Na Omi Judy Shintani, and Shanna Strauss. All identify as women of color; many of them are also queer. Each artist’s work addresses themes of systemic inequality, while also honoring the everyday lives, experiences, and communities of their subjects.

Early conversations with the artists helped me examine tokenism in the art world and language choices in defining the exhibition concept. For example, in response to my use of “marginalized voices,” drawn from Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center (1984) by bell hooks, artist Yolanda López pushed back. She pointed out that the term reproduces traditional power relations and assumptions of who resides in the “center” versus the “margins.”

López’s response made me confront the challenges of language in addressing themes of oppression and resistance through a feminist lens. Similarly, my colleagues—and later, the class—questioned whether the term “woman” is still relevant in the context of intersectional feminism, wanting to ensure that the exhibition was inclusive of trans, gender fluid, and intersex artists and subjects. One of the student curators, Dana Klein, reflected on our choice not to feature the term in the exhibition title and introductory wall text: “I realized the problematic nature of naming a singularly ‘female’ experience; it began to feel nonessential and even tangential to the mission of our artists and the gallery.”

Preparing the Students

Once the artists were secured and the course began, I developed methods for engaging the class in self-reflection and scholarship around identity. In addition to Crenshaw, we read “Re-Thinking Intersectionality” (2008) by scholar Jennifer Nash, for further background on black feminist theory and intersectionality. The 13 graduate student curators in the class all identified as women and most as white. Critical self-reflection with the subject matter was a must: How do power and race inform the curator-artist relationship in museums and galleries today?

To introduce the class to the historical context of feminist and queer art exhibitions in the US, I assigned Maura Reilly’s Curatorial Activism: Towards an Ethics of Curating (2018). Reilly uses the term “curatorial activism” to designate the practice of organizing art exhibitions with the principal aim of ensuring that certain constituencies of artists, “the under- or un-represented, the silenced, and the ‘doubly colonized,’” are no longer ignored. Reilly’s work offered both a theoretical and historical framework for our exhibition.

Once the students were grounded in some of the literature pertaining to the curation of feminist art, we spent a class session at the whiteboard, brainstorming on the language and overarching message for our exhibition concept, or “big idea.” Together, the class composed the following statement: “Expressions of intersectional identities ignite conversations around justice, visibility, and community.” This statement guided their work in developing the exhibition concept and design.

Working with the Artists and Artworks

The next step—and perhaps the most important—was to pair groups of students with an artist whom they would research and interview. Students generated questions, both general and specific to each artist’s practice, including a guiding question asked of all artists: How do you self-identify and respond to being labeled by curators and in the art world?

Students were surprised when several artists avoided the question. Among them was Lenore Chinn, who has documented the lives of San Francisco’s artists, activists, and the LGBTQ+ community for more than five decades. She responded to the students’ question about identity by describing herself as a “documentarian” who simply wished to “represent her friends.” Chinn’s most recognized body of work, her “Family Portrait” series, utilizes traditional portraiture and photorealism to demand social legitimacy for her queer subjects.

Again and again, the artists redirected questions about self-representation. Through this experience, the class came to understand the subtleties of each artist’s unique way of describing their practice as a political act in itself.

Of the works presented, perhaps Yolanda López’s The Nanny (from her “Women’s Work is Never Done” series, 1994) best exemplifies the power of feminist art in calling out the oppression of women of color by white women. In one of the earlier chronological works in “Emboldened, Embodied,” López places a nanny’s uniform between two advertisements, one from National Geographic in 1961 and the other from Vogue in 1991, that exoticize Latin American culture while depicting women of color in subservient positions. The installation calls out the ways that Indigenous and Latina women have been exploited for their labor in the United States by highlighting the asymmetric power relations between white women and women of color.

The Nanny became a catalyst for the students’ critical reflection on the exhibition’s engagement with intersectionality on multiple levels. At an artist roundtable during the exhibition opening, López urged white women in the audience, whom she described as “women of non-color,” to speak out against systemic inequities and racism.

One of the most impactful parts of the “Emboldened, Embodied” exhibition was an interactive “identity quilt” project, loosely inspired by artist Shanna Strauss’s work. In a corner of the gallery, visitors entered a “studio space” framed by a label titled “Origins of the Term Intersectionality.” After reading about Crenshaw’s work as inspiration for the exhibition, guests were encouraged to select a colored index card containing symbolic images on one side and several questions on the back, including “What part of your identity are you most proud of? What part of your identity is in flux? Is fixed?”

After writing responses to these prompts, visitors used twine to attach their cards to others hanging on the wall, forming a paper “identity quilt.” This quilt grew each day over the three months of the exhibition. Sam Sanders, one of the student curators, reflected, “USF is a very diverse community in a very diverse city. We want anyone coming into this space to feel comfortable or reflected in the space.”

Lessons Learned

Bringing museum studies and feminism together into the curriculum was a rewarding experience, and I am eager to take what I have learned to my next project. Teaching a curatorial practicum course focused on feminist art showed me that theoretical context is not enough to train the next generation of curators.

In retrospect, I think more team-building exercises early on would have helped create space for personal reflection on intersectionality within the group. Iyari Arteaga, a student curator, emphasized how “crucial it is for us to acknowledge and discuss the identities and privileges each of us carry.”

What was most important, I found, was listening to what the artists had to say and what they taught me and the students along the way. Through interviews, roundtables, performances, and other public platforms, we need to create more opportunities for artists to speak truth to power.

In training the next generation of museum leaders, we must promote listening, grappling, and self-reflection. The willingness to consider our own positionalities brings stronger relationships with artists; a more thoughtful, critical practice of contemporary curation; and an honest engagement with the ways power and race can inform the curator-artist relationship in museums and galleries today.

Keys to Success

The following can help museum professionals engage in successful, collaborative feminist art curation and programming.

- Promote open and honest discussions of race, intersectional identities, experiences of institutionalized inequalities, and privilege.

- Acknowledge and embrace the differences and multiplicity among feminisms.

- Invite local communities to discuss approaches during the research phase of the project.

- Create platforms (programs, artist statements) for artists to speak for themselves and share their ideas. Remain open to revising messaging, including sharing label copy.

- Design and test interactive activities that promote reflection and community building.

- Discuss museum politics and culture around feminist topics.

Resources

To learn more about “Emboldened, Embodied,” visit usfca.edu/thacher-gallery/emboldened-embodied.

Jenna C. Ashton, Feminism and Museums: Intervention, Disruption and Change, 2017

Kimberlé Crenshaw “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics,” University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

Jennifer Nash, Black Feminism Reimagined: After Intersectionality, 2019

Maura Reilly, Curatorial Activism: Towards an Ethics of Curating, 2018

Paula Birnbaum, Ph.D., is professor and academic director of the Museum Studies M.A. program at the University of San Francisco. She will expand on this topic in the panel discussion “Intersectional Feminism in the Museum” at the AAM Annual Meeting & MuseumExpo in San Francisco, May 17–20.