This year’s TrendsWatch cites buy-ahead pricing as one tool for enhancing revenue and managing attendance. In today’s guest post, Managing Director Tom Schoessler tells us how the Weserburg Museum tried flipping that model, charging visitors as they exit the museum, and explains how that experiment affected satisfaction, behavior, and the museum’s income.

–Elizabeth Merritt, VP Strategic Foresight and Founding Director, Center for the Future of Museums

In an unorthodox pricing experiment, the Weserburg Museum of Modern Art in Bremen, Germany, temporarily dropped the usual day-rate admission fee and connected prices to the time spent at the museum. During two test phases in December 2019 and March 2020 visitors paid 1 Euro per 10 Minutes. Turning admission prices into exit prices had its challenges, but the effects exceeded expectations.

The idea

While pay-per-use pricing has become a widely used scheme in many industries, ranging from parking lots to mobile phone contracts, its application to museums is new. The idea, however, was mentioned quite a time ago, when economists Bruno S. Frey and Lasse Steiner published an academic paper in 2010. Their hypothesis: museum visitors should pay only for as long as they actually utilize the museum, meaning as long as staying longer adds value to the individual experience. This approach, they assume, should lead to higher satisfaction, and prices would be perceived as fairer, since visitors determine their price themselves. This could spur short, spontaneous and repeated visits, but also make it less risky to take a ‘casual look inside’ for those who don’t know what to expect (an argument especially interesting for contemporary art spaces such as ours). But the model might come with downsides: Would it make people spend less time just to save money? Would recreation, muse, contemplation and other such motives suffer? The fear of such negative effects might be the reason why almost ten years later, no museum, at least to our knowledge, had applied the idea to practice.

The regular admission price at the Weserburg is 9 Euros, allowing for an all-day visit to the whole museum. We do not believe that this price keeps the interested out, and reduced rates are available, e.g. for students. But fixed prices might be a barrier for those wanting to make use of their scarce time (e.g. a lunch break), or those wanting to see only a smaller presentation, a certain room or even a single art work of their interest. Such arguments are well known from the debate around a general free admission in museums, with many German politicians and museum makers looking to the British National Museums in envy. But even if free admission could tear down these walls, hardly any museum can afford to forfeit the revenues from ticket sales. The time-based model seemed like a smart way to combine both, access and revenue.

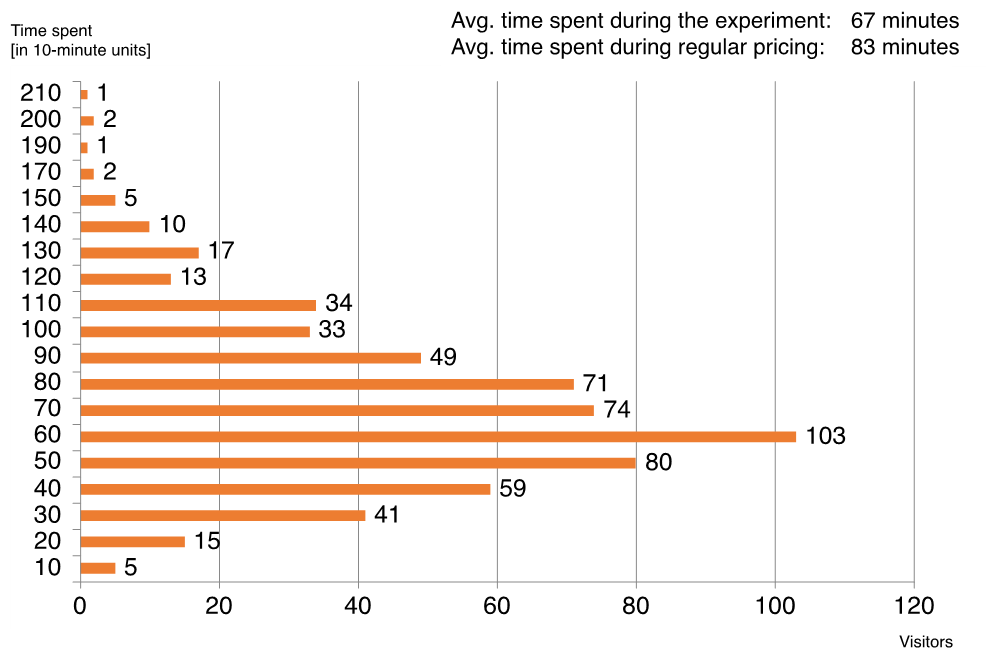

The “1 Euro per 10 Minutes” formula came almost natural, as our regular price of 9 Euros matches the average time spent at the Weserburg, roughly 90 minutes, as a pre-test survey discovered.

The regular price was set as the threshold, i.e. the maximum price payable, even if one stayed all day. The reduced rate was simplified and set at half this, with 4.50 Euro being the maximum. This threshold proved a very important factor, as visitors easily understood they could not lose in this model. A threshold inevitably lowers the revenue per visit, since those leaving earlier pay less, but those staying longer don’t pay more. We knew beforehand, that this effect would have to be offset by an increase in visitation, otherwise the experiment would lose us money. No threshold, on the other hand, could have led to undesired effects such as visitors leaving early or feeling exploited. A higher threshold could have easily been disclosed as a hidden price increase. We later estimated that a threshold of 12 Euros would have led to 4-5% higher revenues, which could be held up against a possible loss of trust.

The results

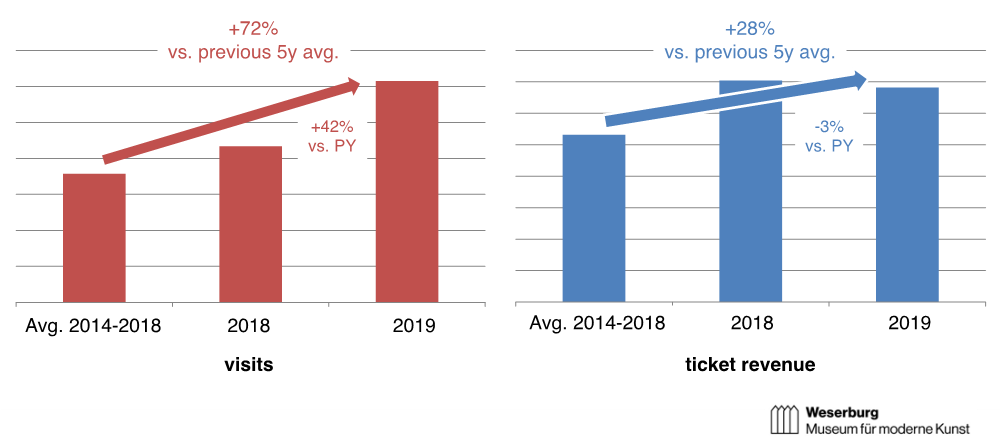

- The number of visits increased by 42% compared to the same four weeks in 2018. Taking the average number of visits between 2014 and 2018, visitation during the “Pay As You Stay” experiment was up 72%. This increase in visitation luckily compensated a decrease in the average price paid (5.55 Euro in 2019 vs. 8.12 Euro in 2018), so that revenue was almost stable compared to 2018 (-3%), and increased by 28% compared to the 2014-2018 average.

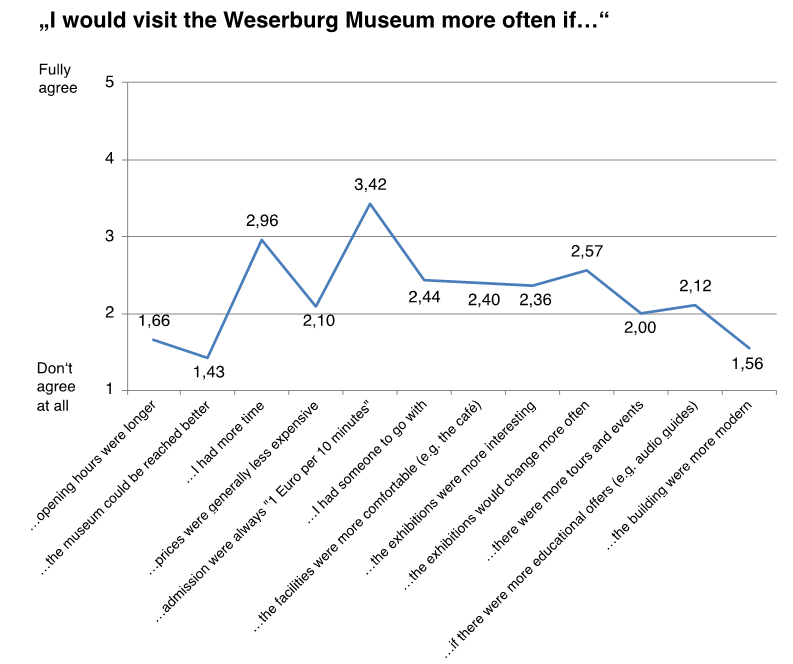

To our surprise, visitors liked the pricing model so much, they said they would come more often if it were applied permanently. It was the most mentioned item in this question of the visitor survey, outscoring “if I had more time,“ the usual number one answer. To this day, visitors regularly ask at the front desk when the “flexible prices” will come back.

To our surprise, visitors liked the pricing model so much, they said they would come more often if it were applied permanently. It was the most mentioned item in this question of the visitor survey, outscoring “if I had more time,“ the usual number one answer. To this day, visitors regularly ask at the front desk when the “flexible prices” will come back. At first glance, the obvious disadvantage of this pricing model is that visitors may feel rushed by the ticking clock. To us, it seemed an unlikely rationale to haste through an exhibition to save money. And indeed, the visitor survey showed that only 4% actually felt pressed for time.

At first glance, the obvious disadvantage of this pricing model is that visitors may feel rushed by the ticking clock. To us, it seemed an unlikely rationale to haste through an exhibition to save money. And indeed, the visitor survey showed that only 4% actually felt pressed for time.- On the other hand, three of four visitors stated in the survey that the pricing model created fair prices. This mainly seems to be due to the individual’s ability to influence their price directly.

- The average time spent at the museum decreased by 16 minutes, a number driven by (intended) short visits. Overall the results show that people take the time they see fit for themselves. They don’t let the clock corrupt their visit. We did not evaluate how visitors spent their time at the museum. Possibly, a person staying “only” 30 minutes had a very intense experience seeing one or two works.

- In the visitor survey, we tracked the Net Promotor Score (NPS), which indicates the willingness to recommend a visit to friends and family. During the first “Pay As You Stay” test phase, NPS was almost a full point higher than during regular pricing days (avg. 7.8 points on a scale of 10). Both in the survey, but also at the ticket counter, we got a lot of positive feedback from visitors. Many appreciated the experiment, enjoyed it as a playful approach, and liked that they had the price in their own hands, without losing anything compared to regular prices.

Since then…

The results presented here were no doubt promising. But it should be mentioned that the model was only applied to single ticket buyers, hence only a part of the visitors. The overall number of visitors surveyed is rather small, so assumptions should be made with caution. We started a second test in February 2020. It was planned for five weeks, but was interrupted after two weeks due to the Covid19-Lockdown. During those two weeks, we could not collect enough data for a solid statistical evaluation. However, the results provide some indications. Visitation was again over 40% higher than the previous year. Revenue was up 10%, both compared to the year before and the December test, due to visitors spending more time at the museum than in December. This is remarkable taking into account that during the second test there was no special exhibition at display, which should lead to fewer visits and less time spent, not more. The results of the evaluation were less clear. We did see again that the model does not make visitors rush. We could not see, however, that the pricing model alone increased satisfaction significantly. What became obvious is that such an experiment must be widely promoted. Media coverage was tremendous in December, when the model was real news. Many came specifically to try the pricing model they read or heard about. That was not the case in the second phase, and advertisement budget was not available.

Our conclusions

The results of our experiment show that this pricing approach, which so far only existed in theory, not only worked in museum practice, but produced positive results. We must, of course, gather more data to understand the effects better, and it is in no way obvious that the system would work in other museums. It is also unclear what the effects would be in the long run. Available studies suggest that prices are rarely the decisive factor in the decision about whether or not to visit the arts, at least in Europe. We must also assume that the promotional effects wear off over time. But even if it is only a minor contribution – if a novel pricing model such as this can support our mission to be accessible, visitor oriented and open to new audiences, we should not leave this stone unturned.

Now, with Germany in the first phase of post-corona life, we are, admittedly, busy getting our operations to run smoothly. As soon as we and our visitors are used to a museum with social distancing, face masks, new directions and so on, we will implement “Pay As You Stay” again. It could actually be a great fit for these times, as it reduces the financial risk of a museum visit significantly. If it proves a feasible pricing model, both financially and with regard to accessibility and visitor satisfaction, we will keep it in place. If not, we’ll be comfortable with this finding, too, and try something else. But try we will.

About the museum:

The Weserburg Museum für moderne Kunst is Bremen’s museum for contemporary art, displaying all forms of art production since the 1960s. With over 5,000 square meters of exhibition space, it is one of the larger institutions of its kind in Germany. It is a private entity, but heavily relies on public and private funding.

www.weserburg.de

Twitter: @weserburg

Instagram: weserburg_museum

About the author:

Tom Schoessler is managing director of Weserburg Museum für moderne Kunst in Bremen, Germany. He teaches arts management at several universities and has published books and articles on pricing in the arts sector. You’ll find him on Twitter as @schobler

You can download some images of the museum as well as Tom’s portrait photo here:

https://weserburg.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Fotos_1-Euro-pro-10-Minuten.zip

How do you track how long someone has been in the museum?

When entering, visitors receive a blank ticket with only the time of entry on it. When leaving, they come to the front desk again, and the time of exit is recorded. A simple calculation form at the register (potentially integrated in the ticketing software) tells the price. Hence visitors pay before leaving, which led Frey/Steiner to establish the term “exit prices” as apposed to admission prices. This worked without a problem in our case, but indeed depends on the architecture & design of the ticket desks.