Riches, Rivals, and Radicals: A History of Museums in America has been read by students, professionals, and museum lovers alike since its first publication in 2006; its public television adaptation has nearly half a million views on YouTube. This October, the American Alliance of Museums will release the award-winning book’s new edition—its third.

In this interview, author Marjorie Schwarzer describes how she updated and reframed the book’s text and images not only to reflect developments in American society and the museum field, but also the evolving perspectives that she and her fellow professionals have brought to their work.

Why is 2020 a good time for a new edition of Riches, Rivals, and Radicals?

History doesn’t foretell the future. But it is a powerful tool to help us put things in perspective. The first edition of Riches, Rivals, and Radicals was written to celebrate AAM’s centennial. The intent was to document the astonishing growth of the museum field since AAM’s founding in 1906. It examines museums thematically, through the evolution of their architecture, collections, exhibitions, and ultimately, politics and the money trail. The book describes how key events in the nation’s history—wars, economic booms and busts, civil rights movements, natural disasters, political upheavals—have impelled significant shifts in all facets of museum practice. It’s a complex and fascinating story.

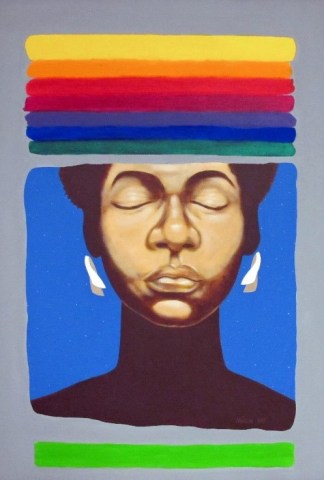

Today, our nation appears to have reached another tipping point—we’re in the midst of escalating economic inequality, environmental collapse, a threat to constitutional democracy, and an important dialogue on racial justice on top of a pandemic. It’s a critical time to re-visit what has happened within museums during and after societal upheavals so that we can imagine new possibilities and be open to change.

To paraphrase the opening lines of the new edition, extraordinary events, such as the ones we are living through right now, shape generations. In turn, those generations shape events into the museums of the future.

In which ways did you update or reframe the book? Why?

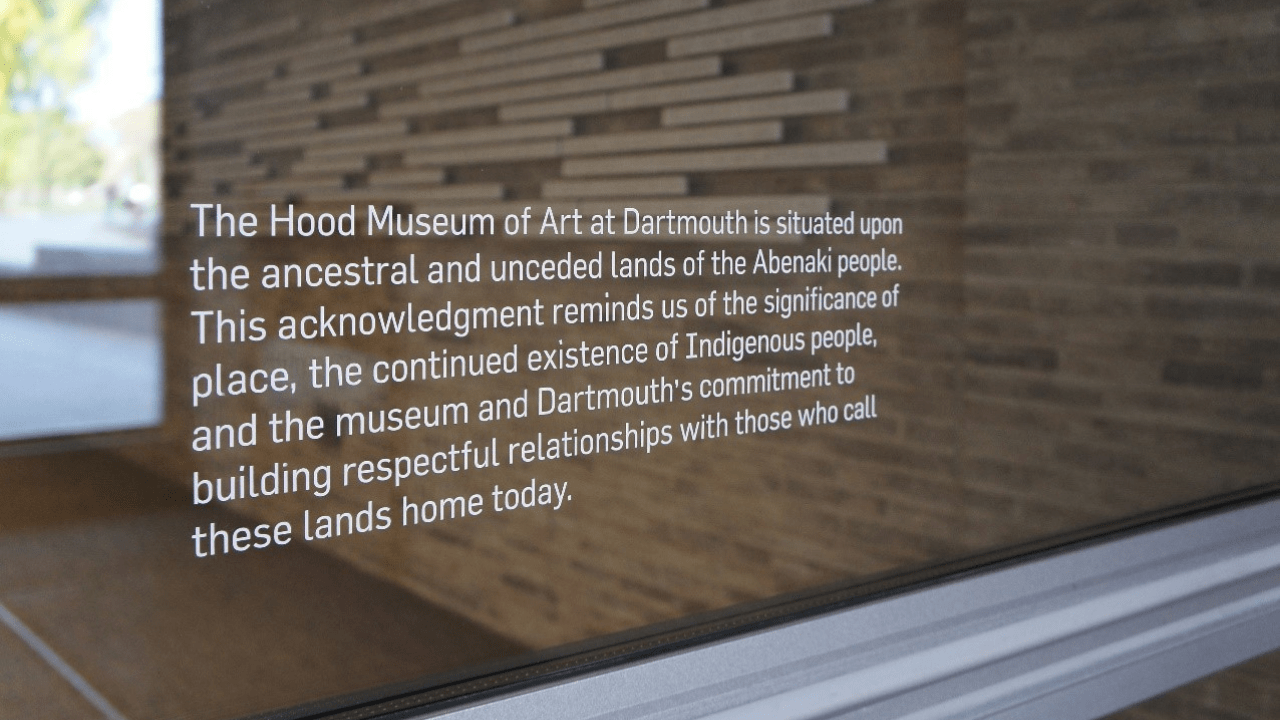

At first, I was simply going to write a coda, which is what I had done for the second edition. But in reading through the text, I realized I had the opportunity to reframe the entire book within the context of contemporary dialogues in the field such as social justice, gender equity, and decolonization.

I also questioned assumptions I had made as a writer and researcher fifteen years ago that might not resonate with today’s readers. This—as well as valuable feedback from my graduate students and colleagues—resulted in a lot of changes.

I punched up some of the prose, shortened or cut redundant sections, and surfaced more stories for each chapter, especially about the role of some of the radical and courageous thinkers and doers who pushed museums to extend their reach and relevance. I benefited not only from eagle-eyed readers and the gift of fifteen years of perspective, but from archives that I hadn’t known about or were unavailable at the time I wrote the first edition.

I found untold stories (or illuminating details to stories already in the book) dating back to the early twentieth century. I tried to show more clearly how progressive educators and others within museums worked actively to fight against racism, social injustice, and inequity. Not all of these stories are uplifting. Individuals often faced considerable backlash. Others made faulty or clumsy assumptions. Some important programs ended when the money dried out. But they are part of the story of the difference individuals can make in an institution’s history.

In addition to a new introduction, as well as a foreword by Laura Lott, there is also a new chapter titled “Museums and Society.” In this chapter, I trace how and why museums have been such contentious places right from the get-go. From their foundational days, people worked at odds with each other, sometimes even within the same museum! And still, for a host of reasons that you can read about in the book, the number of museums, as well as audience numbers, continued to grow. The Great Depression, civil rights era, and late-twentieth-century culture wars are times when museums showed a remarkable progressive spirit and offer many positive lessons that can help us grapple with where we are today.

Another change in the text may seem subtle, but I believe it is quite important: identifying people by name. Thanks to the efforts of so many feminist scholars, Wikipedians, post-colonialist researchers—and with a shoutout to Laura Fry at the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa—I provided, as best I could, women’s first names as well as the names of Native American artists and other heretofore anonymous contributors to the field.

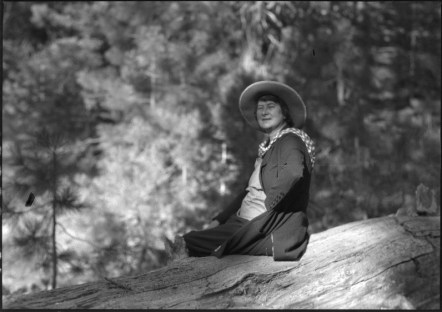

There are many examples, but here’s just one: I learned that the philanthropist who backed the work of the legendary Newark Museum director John Cotton Dana in the 1920s is known in the history books as “Mrs. Felix Fuld.” Actually, she’s “Carrie Bamberger Fuld,” a person and force in her own right. Another woman of note is Delia Akeley, wife of the legendary taxidermist Carl Akeley. Not only did she once rescue her husband from the clutches of an angry bull elephant, but she was an accomplished naturalist in her own right.

Another change of note is that since the first edition of the book in 2006, some museums have taken it upon themselves to openly confront some of their past practices. A powerful example is how the Field Museum has dealt with the painfully racist Nazi-era exhibition Races of Mankind. That re-interpretation is now part of the story of how museums can reckon with the past in order to promote healing.

So, in summary, what I ended up doing was decolonizing my own book.

I know that you wanted an element of fun and delight in the book, through both the text and the images. Why did you think this was so important?

As you know, I’ve always believed that people learn more when they are having fun. While people visit museums to see works of historical, cultural, and aesthetic importance, they are also drawn by curious and oddball things—like the only intact set of George Washington’s dentures, sets from famous TV shows, outrageous fashion statements, and celebrities’ vehicles.

Why not use the strange and compelling stories behind such acquisitions—or the egotistical exploits of architects, collectors, and others—as hooks for luring readers into the museum’s larger history?

What do you hope readers will come away with from the third edition?

I believe that by understanding and reckoning with their history, museums can serve as places of healing, and as platforms for people to develop new ways to picture the world and each other. That is why I cast the story of museums within the larger history of the American economy, technology, struggles for civil rights, and other forces. To me, and what I hope readers will see, is that the museum story is one of persistence, resilience, and hopefulness.

If you were to plan a fourth edition, what would you be interested in seeing there?

Clearly, a book such as Riches, Rivals, and Radicals is a broad sweep. It draws upon the work of many hundreds of researchers and practitioners. After ten or twenty years, I have no doubt that there will there be manifold new museum stories to tell, and that scholars in the field will have filled out the stories I have already told and unearthed new ones.

From a feminist perspective, Anne Ackerson and Joan Baldwin broke important ground with their book Women in Museums: Lessons from the Workplace, but our understanding of the role of women in establishing and sustaining museums across the nation will doubtless be vastly expanded. For instance, while I found out Carrie Bamberger Fuld’s name, it is likely that her contributions will eventually reach the light of print. And there are many, many more people like her who we don’t even know about yet.

There is a need for more research on museums from a queer perspective. We know that LGBTQ+ people have made significant contributions to the field, but we know little of how their sexual orientation and life’s experience influenced their work.

In regard to museums’ role in perpetuating institutional racism, materials buried in archives still need to be analyzed. As just one example, I would love to read a more thorough deconstruction of the impulses behind the founding of Colonial Williamsburg and other such sites within months of Jim Crow laws being implemented.

Finally, the third edition went to press in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic and before the George Floyd murder that sparked the #BLM protests of summer 2020. The outcome of the 2020 election is still unknown. The third edition shows us that there are inventive and courageous ways to respond to an unknowable future. A fourth edition would tell us whether museums heeded the call of the moment.

The third edition of Riches, Rivals, and Radicals: A History of Museums in the United States is now available for pre-order.