I am going to break a long silence to weigh in on the current conversation around NFTs, addressing four issues that have come up repeatedly in my conversations with people inside and outside the museum sector. These questions are (loosely paraphrased):

- What’s with the crazy NFT market?

- Is crypto (blockchain generally, cryptocurrency and NFTs specifically) really going to democratize commerce, wealth, and art?

- Is blockchain bad for the environment?

And finally,

- Should my museum jump into crypto/NFTs?

But First, a Brief Primer

If you don’t already understand what the heck blockchain is, here’s a super brief explanation. Blockchain is a digital system that lets users share records and data related to transactions across a distributed, decentralized network, using encryption to ensure the data is secure and immutable. The resulting “digital ledgers” are both private (allowing users to remain anonymous) and transparent (in that they can be left “open” for anyone to read). For a more in-depth explanation of blockchain and how it works, read this chapter from TrendsWatch 2019.

The breakout application of blockchain was digitally-based currencies (cryptocurrencies) that support the creation and exchange of wealth. People who allow their computers to be used as nodes in a distributed blockchain computing network are rewarded with tokens—units of cryptocurrency associated with the particular platform running on that node network. Cryptocurrency coins are “fungible tokens”—identical and interchangeable, just as one unit of traditional fiat currency, say a dollar bill, is identical in value to another. Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are unique in some way, making them non-interchangeable. NFTs may be one of a kind (like an original painting), or part of a limited series each with a unique identifier (like a series of signed and numbered prints). NFTs can correspond to a piece of digital anything—music, visual art, a tweet.

What’s with the Crazy NFT Market?

Let me start by making it clear that I have no opinion on whether NFTs are “worth” the sometimes astronomical sums being paid for these digital collectables. Though if pressed I will admit the current enthusiasm around NFTs reminds me of the Dutch tulip craze that swept across Europe in the early 1630s. (At its height of that market bubble, a single bulb of the rare “Viceroy” variety sold for ten time the annual wage of a skilled craftsman.) Spending $69 million for a jpg file doesn’t seem inherently stranger to me than paying $18k for an invisible sculpture, or $120k for a banana duct-taped to a wall. Things (tangible or intangible, ephemeral or durable) are worth what people decide they are worth.

That said, whatever people think an NFT is worth, they ought to at least know what they are buying. The token itself usually doesn’t contain the data that makes up that digital thing (which would eat up too much space, and money, on the blockchain). Instead, an NFT is a record of ownership and authenticity, not the digital thing itself. Many NFTs contain a URL that points to the data that constitutes a digital item being tied to the blockchain—if that link breaks, or the host account isn’t renewed, you own…nothing.

Value aside, there are a lot of issues swirling around the NFT market, among them:

- Widespread copyright infringement, counterfeits, plagiarism, fraud. There has been an explosion of theft from automated bots scraping visual images from artists’ online galleries. This is so rampant that several major NFT marketplaces recently halted most NFT transactions because of unbridled sales of fakes and plagiarized tokens.

- A huge number of NFT sales are turning out to be fake, as traders buy their own NFTs to inflate the price—a practice called “trade washing.”

- Some vendors offer “NFTs” for sale without writing them into the blockchain, which essentially voids any claim to traceable authenticity and uniqueness. This practice, called “lazy minting” is explicitly allowed by OpenSea, one of the largest marketplaces for NTFs and other crypto-collectibles.

Bottom line, the NFT market is currently a wild-west landscape of minimal regulation and oversight, and buyers looking to “invest” in NFTs should be on their guard.

Is Crypto a Force for Social and Economic Good?

When blockchain, and cryptocurrencies, burst on the scene, they were hailed by proponents as yet another digital disruption of traditional power structures that could make wealth more accessible and decision-making more democratic. However, there is a common pattern of companies using digital innovation to disrupt traditional economies in order to generate private profit, in part by exploiting the gap between the introduction of new technologies and the introduction of regulations designed to curb their abuse. Tech startups tend to play up the benefits and downplay the negative effects of such disruptions. When the two major ride-share services launched, just over a decade ago, they dwelt on how the “sharing economy” could reduce car ownership, and hence pollution, and provide accessible, flexible work opportunities to folk with time and wheels to spare. As it turns out, ride-share companies generate 70 percent more pollution than the trips they displace, increase congestion, and undermine public transportation. Their profits are built on exploitative labor practices, and the companies are engaged in a running battle to defeat legislation that would force them to actually employ their drivers, with attendant labor protections, rather than treating them as disposable contractors. They did indeed divert wealth from one set of people (who owned taxi medallions) to another (the CEOs and shareholders), but not in a way that fostered economic equity.

Similarly, businesses built around blockchain play up how the technology can make the world more transparent, equitable, and democratic. And indeed, by disrupting the middleman, whether that is a bank or an art dealer, they have created economic access and financial opportunities for some people who were shut out by traditional power structures. Some artists, for example affirm that NFTs provided them with access and exposure they never had through traditional art spaces, which are often predominantly white and male. (Also, during the pandemic, sales of digital art buoyed artists’ incomes while tourism tanked and traditional place-based markets shut down.) But cryptocurrency, which is the economic driver for blockchain platforms, is especially advantageous people who want to evade oversight, detection, and regulation, often for nefarious purposes that include money laundering, extortion via ransomware, and illegal commerce. While there is a lot of talk about how blockchain could, theoretically, reduce wealth inequality by distributing ownership and control of capital, in actual practice the distribution of Bitcoin (for example) mirrors wealth inequality overall. Speculating in cryptocurrency is a high-risk venture, with extreme and rapid cycles of boom and bust, and people who already have deep financial capacity are best able to bear that risk.

So, while blockchain generally, and cryptocurrency specifically, does afford some opportunities for people previously excluded from or disadvantaged by traditional gatekeepers, like banks, or art dealers, it affords even more opportunities for people who are already economically and technologically privileged, and well-situated to exploit the disruptions created by new mediums of exchange.

Is Blockchain Bad for the Environment?

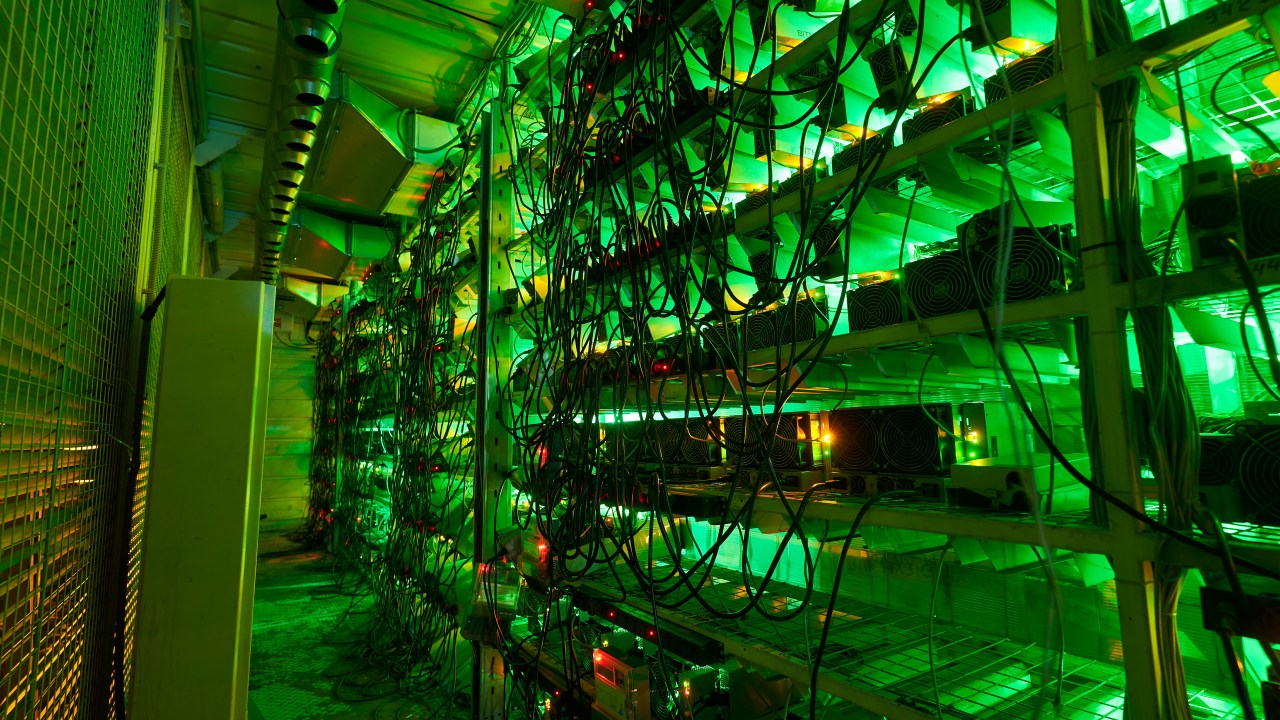

The simple answer is yes. Cryptocurrencies are based on what is known as “proof of work,” so-called because crypto networks like Etherium and Bitcoin force “miners” to burn through masses of computing power to solve arbitrary math problems in order to validate transactions and mint new tokens (i.e., coins). This system is, by design, massively resource-intensive, using a high bar of energy consumption to make it hard to hack or game the system. Essentially people pay for power (with everyday “fiat” currency) and transform that money into cryptocurrency via mining. The energy use isn’t a bug; it’s a core feature of the system. NFTs, in turn, inherit the environmental costs of the blockchain, both because they are built on the same system for verifying transactions and because they are usually bought and sold using cryptocurrency.

How big is that environmental cost? Bitcoin mining alone consumes 0.5% of all electricity used globally (seven times Google’s total usage) and has increased tenfold over the past five years. Looked at another way, Bitcoin’s carbon footprint is equivalent to that of New Zealand (about 37 megatons of CO2 per year). And of course, companies that profit from issuing cryptocurrencies want to grow—which means more mining, more energy consumption, and more carbon pumped into the atmosphere. (And as a side effect, mining generates a massive amount of electronic waste, difficult to recycle or dispose of safely, because the hardware used to mine crypto burns out so fast.) As is common with rapidly emerging technology, the world is left playing catch-up. China has banned bitcoin mining because of the energy cost, and the European Union is considering regulating cryptomining due to environmental impact.

Raise the issue of energy consumption with crypto-enthusiasts, and they will say they have plans to “go green” through use of renewable energy and/or a pivot to a different system for verifying transactions on the blockchain and generating tokens. Both these arguments have their flaws.

First, let’s look at renewable energy. Is solar power less damaging to the environment than natural gas or oil? Yes, it is. But it still has a negative impact on the environment, as does any form of energy production. Solar power entails land use, habitat loss, and the use of hazardous chemicals in manufacturing. Wind turbines kill bats and birds, generate noise pollution, and generate downstream impact via manufacturing of component parts, transportation, and eventual dismantling and disposal of decommissioned equipment. Hydroelectric dams destroy wildlife habitats and disrupt migratory pathways. Energy generation is a classic case of “there is no such thing as free lunch.” While there are more and less environmentally destructive ways to generate power, our overarching goal, to create a sustainable world, must be to limit our energy use. As Digiconomist founder Alex DeVries has pointed out, “You cannot sustainably waste resources—using renewables for crypto mining is no solution.”

As we set sustainable limits on power consumption, we will have to prioritize the power we do generate for critical functions like operating water treatment systems, heating buildings in the winter, and powering hospitals. In February of this year, the energy draw of crypto-mining contributed to the collapse of the power grid in Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan. There is concern a similar overload could happen in Texas, which is poised to be the new world capital of bitcoin mining. (This in a state that has already found its power grid to be inadequate in the face of extreme weather events like last spring’s deep freeze.)

The other proposed method of reducing the environmental impact of crypto is to transition from energy-intensive proof-of-work to a system called “proof-of-stake.” Basically, instead of forcing miners to burn massive amounts of power, the system gives people the opportunity to validate transactions by putting their cryptocurrency up as collateral. It may be less energy-intensive (though again, emphasize “less”), but it seems to me that it upends the equity arguments about crypto, since it essentially becomes a different form of pay-to-play, with wealth determining an individual’s ability to influence the system.

At the end of the day, in crypto, as with any area of practice (tourism, fashion, construction), we can ask how to make it less destructive through better design, or carbon offsets, or tweaking the chain of production. But in the end, we need to consider whether the best way to limit impact is to simply do less: less travel, fewer new purchases, more adaptive reuse of existing things, whether that’s clothing or buildings. In the case of crypto, we may need to ask whether the costs simply outweigh the benefits. What can the blockchain do, uniquely, that can’t be done as well and more sustainably by traditional systems? Is cryptocurrency more accessible, equitable, and efficient than traditional fiat currency, especially if those traditional dollars can be moved around via simple digital platforms like Venmo or Paypal?

Should My Museum Jump on the NFT/Cryptocurrency Bandwagon?

I guess it’s clear from the commentary above that I have reservations about certain aspects of blockchain and applications built on those platforms. But I also acknowledge that the impacts of cryptocurrencies, and NFTs, are not uniquely bad. Museums make choices every day that determine the impact they have on the world. Many run massive HVAC systems to protect their collections. That being so, it is admirable for museums to look for the most energy-efficient systems possible, and to rely on renewable energy sources when they can. Museums build and ship exhibits all over the world. Again, it’s commendable to minimize the carbon footprint of those activities, from choice of construction materials to methods of transportation. Museums operate food services for visitors, and some make a point of serving healthy food, raised in sustainable ways by local farmers, using reusable or compostable utensils, and selling water bottles instead of bottled water. All admirable choices that help, incrementally, to make the world a better place, or at least mitigate the damage that comes from doing business at all.

So, when it comes to decisions about engaging with the crypto economy, I encourage you to start by discussing a few critical issues:

- Is the nature and impact of crypto (NFTs and cryptocurrencies) consonant with your organization’s mission and values? The answer to that will probably be different for a museum devoted to preserving the natural world than, say, for a museum devoted to exploring innovation or emerging technologies. Be aware that whatever decision you make will be examined by the public. Even people with only the haziest understanding of NFTs may be aware that they are “not green.” (The popular comic strip Mark Trail features a running rant about the eco-impact of NFTs.) The World Wildlife Fund was forced to discontinue sales of NFTs themed around endangered species, due to an outcry on social media around the dissonance of that source of funding and their environmental mission.

- Are you primarily interested in NFTs because they are new and exciting, or is the format a natural fit for a particular project or theme in your collections and research? For example, the Whitworth museum at the University of Manchester issued an NFT based on William Blake’s Ancient of Days as a way to test alternative models of financing social practice. As the project’s site explains, “By minting a collection-derived NFT for sale on the open market, this experiment will explore the potential of directing new flows of private digitised capital into social capital.” (The museum also chose to issue the NFT on a proof-of-stake network to minimize the associated energy consumption.)

- What are the risks to your organization? That assessment needs to encompass both upside and downside risks, ranging from economic to reputational. Yes, you might make a bundle by issuing NFTs based in some way on your collection. You might also lose money, net, if the total cost of that project exceeds the money it brings in. Per the WWF example above, museums would do well to assess reputational risk as well, an issue that isn’t confined to NFTs. You may be weighing whether to accept donations in the form of cryptocurrencies, given that cryptophilanthropy is growing fast. But it’s worth asking how, beyond seeming cool, that makes the opportunity to support the museum more equitable or accessible to the community it serves.

So that’s a written version of my half of the conversation you and I might have had over coffee at a conference. I’d like to hear YOUR half as well. Please weigh in via comments, Twitter (tagging @futureofmuseums), or by shooting me a line at emerritt (at) aam-us.org.

Speaking of chatting over coffee–I would love to connect with you at #AAM2022 in Boston, May 19-22. I’ll be teaching a workshop on strategic foresight, as well as leading discussions around this year’s edition of TrendsWatch, soon to be released. Registration for the conference is open, and I hope to see you there!

Thank you very much for this very interesting article !

I am a master student at the University of Paris Sorbonne and I am doing a master’s thesis on the place of NFTs in the new museum practices. I would be honored to discuss these issues with you. Let me know if you would accept such a discussion.

Best Regards,

Marie