This article first appeared in the journal Exhibition (Fall 2023) Vol. 42 No. 2 and is reproduced with permission. If you don’t read the journal, learn how you can subscribe to Exhibition to receive your copy of the full upcoming issues.

Imagine being a visitor or a member of a visiting group walking into the lobby of a museum you’re familiar with: you see a sign proclaiming “you belong here.” How would you get a sense of belonging in that space? What would you see, hear, and feel? Where is belonging located in an experience, in the collection of spaces that make up a museum: exhibits, lobbies, cafes, restrooms, and more? For some time, museums have been focused on creating equitable, accessible, and inclusive spaces for a diversity of people containing a multiplicity of perspectives, identities, and life experiences.[1] Recently, some museums have nested the concept of belonging in this work, often equating a sense of belonging to feeling comfortable, included, welcomed, and/or represented, in an effort to increase a sense of belonging among audience groups who have not had equitable representation in the museum context.[2] Yet, without a shared and visitor-centered understanding of belonging, how can the field adequately understand what belonging means to visitors and design for belonging in order to make progress on these goals?

Through work at our own institution (Science Museum of Minnesota) and three other institutions that opened their doors for data collection (Denver Museum of Nature and Science; Great Lakes Science Center in Cleveland, Ohio; and Museum of Science, Boston), we carried out a research study to define belonging in science and natural history museums from the visitor perspective. The findings shared in this article represent the experiences of visiting groups from across all four sites.[3]

Our study used a qualitative photovoice methodology, with visitors being asked to take photographs of moments that mattered to their sense of belonging during their visit. We wanted groups with a wide range of identities and with varied experience with museums to participate and used both regular museum communications and specific invitations to communities to recruit a variety of individuals, particularly those with identities typically excluded in STEM, specifically BIPOC, women, LGBTQ+, and people with disabilities.

Across the 72 groups that participated, 50 percent included at least one member who identified as BIPOC, approximately 20 percent of groups had at least one member who identified as LGBTQ+, and about 25 percent included at least one member with a disability. We invited groups of any size or relationship to take part. Each group was asked to stay at least two hours and to complete an interview at the end of their visit. To ensure that we reduced potential barriers to participation, the study covered the cost of the visit, including admissions, a per diem for food, and parking/transportation fees. In addition, each group was compensated $100 for their time.

Groups took photographs of moments that mattered to their sense of belonging during any aspect of their visit and then discussed and reflected on the most impactful moments (and photos) during their post-visit interview. By the end of our study, we had spoken with over 230 adults, teens, and children who took well over 2,000 photos. It was important to us to take a justice-focused approach to this work: by intentionally recruiting participants from historically marginalized groups, by centering visitor voices in asking them to choose the photos they wanted to talk about, and by building a definition of belonging for museum spaces from the ground up.

Each photo included in this article was taken by a visitor to represent a moment that mattered to their sense of belonging during their visit. Where a visitor photo captures their sense of belonging, a picture truly is worth a thousand words. Visitors were unafraid to share powerful moments from their visit, including moments that affected them individually and as a group, as well as moments that were positive, negative, or, at times, a mixture of the two.

Moments That Matter to Belonging Occur across a Visit

Across all groups, moments of belonging occurred across the whole visit: from feelings of whimsy, invitation, or anticipation as visitors first come through the lobby doors to a challenging moment in an exhibit hall, and more. For example, this visitor’s photo and comments reveal how belonging is positively supported across the visit, starting with the “welcoming” and familiar experience of the lobby:

“I grew up in [the rural part of the state]…but we’d come up to [the city] once a year.… That dinosaur has been there since before I was probably her age, in the same spot…and it just is very welcoming.… It’s like, “there’s the T-Rex, okay.” I feel like I’m in the museum as soon as I see that” (fig. 1).

The group went on to describe the aesthetically pleasing space of the cafe and an engaging staff-led program in the exhibit halls as contributors to their feelings of belonging. While moments that matter to a visitor’s sense of belonging often occurred in exhibit halls, those moments intersect with experiences beyond. That is, a positive moment of belonging in one exhibition might combine with negative moments in the restrooms or mixed positive and negative moments felt in the lobby to create an overall sense of belonging in the museum. The data from our study shows that we need to pay attention to the entire visit, not just exhibitions, if we want to create belonging for visitors.

Belonging Is Felt at the Group and Individual Levels

For many science and natural history museums, a key priority is engaging visitors in exhibitions through interactive experiences that allow them to touch, play, and learn together. We found that visitors feel belonging in our spaces based on the ways they and their group are able to engage. For one multigenerational group in a science of music exhibition, that adults and children could learn and play together in a space impacted their group’s sense of belonging. As one of the adults in the group described:

“So, you know, they were enjoying themselves and as a parent you like seeing that…belonging, welcoming, because it invites multiple people to do something”(fig. 2).

This highlights an under-discussed aspect of belonging in museums: belonging is felt not just on an individual level but as a group. Where an individual in a visiting group is not supported—perhaps their identity is not represented, or their access to an exhibit is impeded—the impact is felt by the unsupported individual and the group as a whole.

Belonging Is Dynamic and Co-Created

Our study shows that a visitor’s sense of belonging is dynamic—actively created moment by moment by the visitor themself. This has important implications for museums, especially as they turn to the concept of belonging to frame their diversity, equity, and inclusion goals. Through their photos, the visitors in our study showed that their sense of belonging was shaped across their visits and in response to the context of the museum for that day.[4] Museums, therefore, cannot wholly control visitors’ sense of belonging; visitors freely co-construct their feelings of belonging and contribute to the belonging of others in the museum space through their actions. For example, when a multigenerational group came across structures that resembled a home in Mexico, one group member exclaimed:

“Esto yo lo conozco…Mi rancho. Mi infancia. [I know this…My ranch. My childhood].”

For other adults in the group, it was her active storytelling that led to a sense of belonging:

“This one I’m actually pretty personally attached to…it’s really nice to see somebody reminisce and then you get to learn a lot from them and a lot from where they came from and you learn to appreciate what you have also.”

Museums can design spaces for belonging but also need to be flexible and adaptive to the context and to the people who are actively constructing spaces of belonging for themselves.

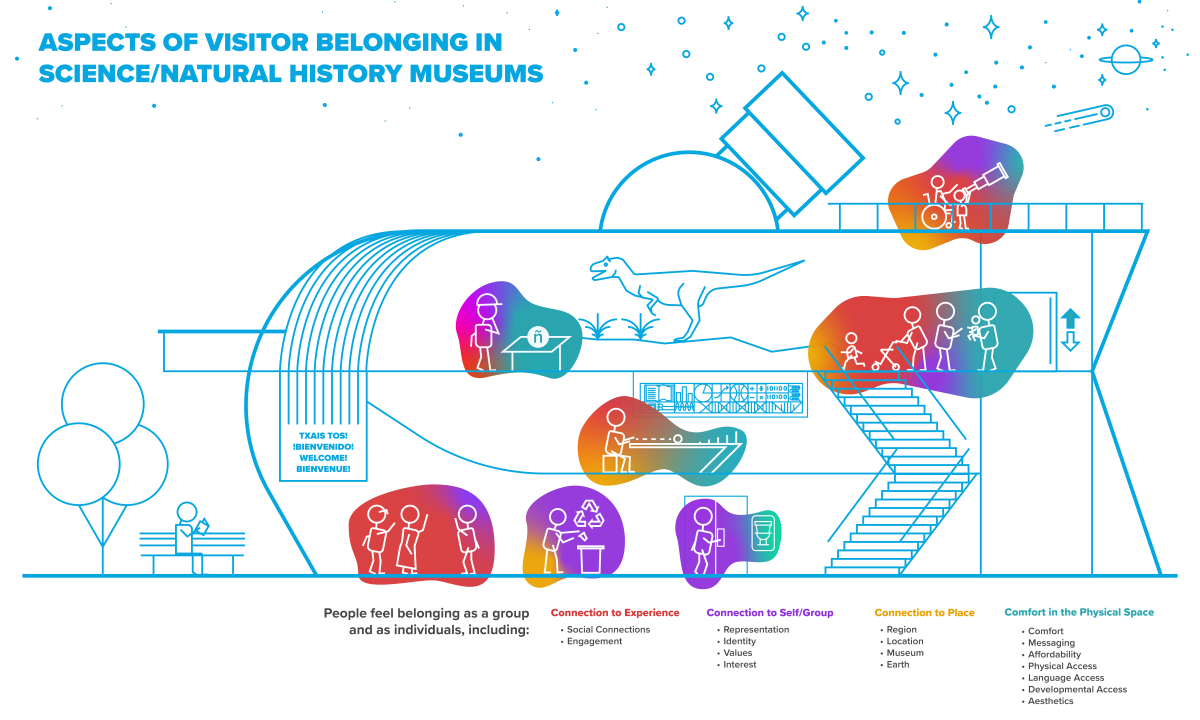

Four Ways of Feeling Belonging

Visitor photos and stories highlighted and helped us to identify four key categories that we believe are essential in defining belonging. While belonging is a complex concept through which to consider exhibit and museum design, we believe that reflecting on these four overlapping ways that visitors describe belonging in the museum will give designers a better chance of creating spaces in which visitors can freely construct their sense of belonging:

- Connection to Experience

- Connection to Self and Group

- Connection to Place

- Comfort in the Physical Space

These categories have implications for the broader placemaking efforts of museums. Importantly, while we are highlighting each category independently, visitors may feel belonging more strongly when moments of their experience simultaneously engage multiple ways of feeling belonging. For example, a family group looking at a display that associates astronauts with their hometowns might feel belonging through the act of engaging with that exhibit together, by noticing the hometowns of the astronauts and finding places they know or have been to, and by noticing the different identities of the astronauts that connect to their own group. These happen simultaneously in such a display and might result in a strong moment of belonging.

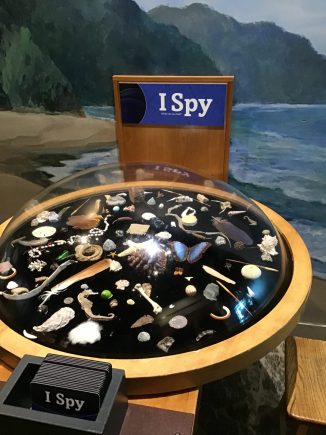

Connection to Experience

Museums are designed with the social experiences of visitors in mind—what they touch, see, and talk about during their visit—and these social experiences, in turn, relate to belonging. Belonging is inseparable from what people do in the museum and how they build connections (e.g., with others and/or with the subject matter). We heard from a pair of college students playing with an I Spy exhibit alongside other visitors that working together to find the items in the display:

“…really…fostered a strong sense of belonging just because we felt kind of almost like a community” (fig. 3).

These visitors are describing a moment of belonging that not only supports social connection within their group, but also supports social connection with other groups.

Engagement within a visitor’s group, with other visitors, and with museum staff can support or impede belonging during a visit. When visitors were engaged in positive experiences as a group, belonging flourished. In contrast, visitors most often reported threats to their sense of belonging when group interactions were stifled by other visitors or by staff, or—if they identified as a historically marginalized group in museums—when they experienced microaggressions during their visit. This example from a visiting group waiting for another group to finish using an exhibit shows how belonging can be compromised in these interactions:

“Two people were sitting there, even though [our child] had been waiting…to engage with it. I think because it’s right next to the door that [they felt] ‘Oh, I can just clearly not pay attention to anybody else who’s there.’ What it felt like to us is that…heterosexual couples [felt] like they had more of a say to go into things, [w]here we, who don’t fit as neatly into that, did not get to.”

Experiences within the museum that are designed to foster both within- and between-group interactions are critical. Equally important is our ability to adjust experiences as we notice visitor behaviors that negatively impact belonging.

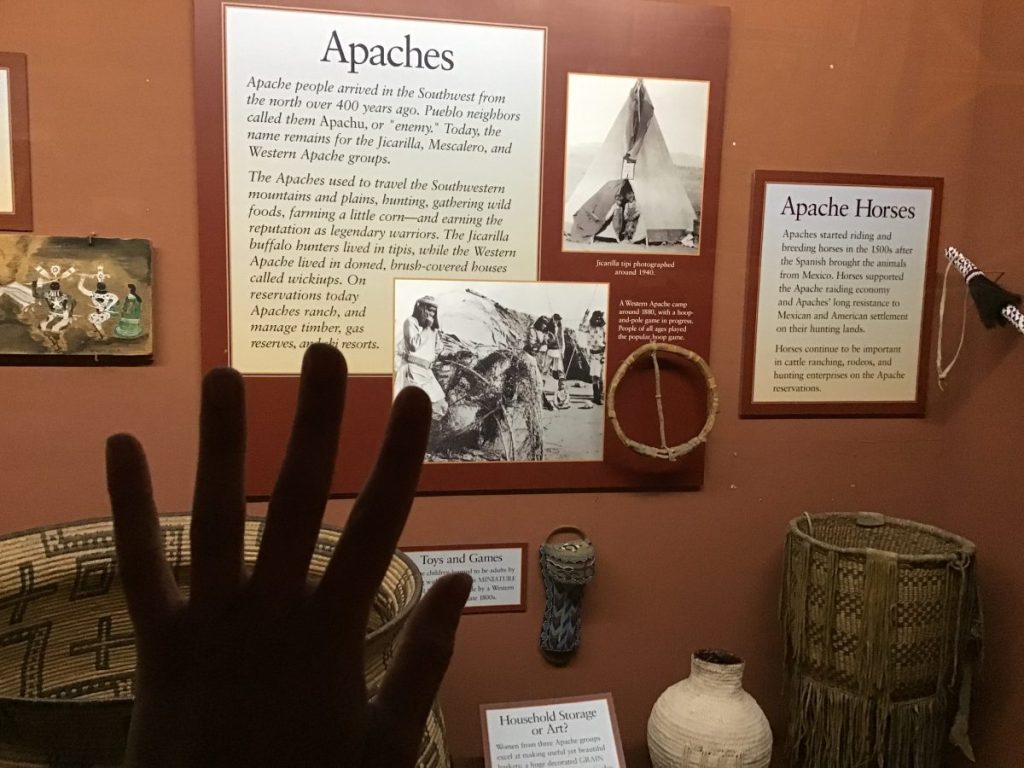

Connection to Self and Group

Where visiting groups feel or explicitly see connections to their own identities, interests, and/or values, they often report a strong, positive feeling of belonging. However, if the museum’s representations of identities are biased or missing, or the museum doesn’t offer an array of experiences to align with a variety of visitor interests, belonging will be negatively impacted.

For example, stocking culturally relevant foods in the museum cafe, such as agua fresca, shows care—the museum expects visiting groups for whom that food is recognizable. As one participant reported:

“Being able to go to the cafeteria and seeing something that you’re familiar with, that’s comforting. That gives you a sense of belonging that they’re inclusive of their food choices.”

Still, representing identity in a museum space can be complex. One group intentionally included their hands in some photos as a way of literally placing themselves in the frame and described the ambivalent feelings they experienced at a particular exhibit:

“That was like a positive/negative [because] we do have some connection with…this particular nation…. Apache is actually not a word that they call themselves because it means enemy. But it’s used…. Yeah, that was kind of frustrating. And yet…of course, I did feel…connected too, right?” (fig. 4)

This visitor is wrestling with seeing themselves and being frustrated by the representation on offer, which should cause museums to reflect carefully on the choices they have made and their impact on visitors. When museums take care to understand the nuances of identities and visitor relationships to objects and spaces, they can make better design and curatorial choices. Such is the case here, where the museum is in the preliminary stages of redesigning this exhibit.

Visitors may also feel belonging when they see their identities reflected in unexpected ways. See how a visitor who is deaf constructs their sense of belonging while engaging with an exhibit that allows them to see their face reflected in an astronaut’s visor:

“Because [space is] dark and communication might be challenging, there’s a lot of gestures that might happen. So, we connect with that just because of the lack of sound, and that’s how we communicate and use our own language” (fig. 5).

This exhibit was not designed with representation of deaf audiences in mind. It was the openness of this experience that allowed this visitor to connect their identity—and the identity of their group, a family with two deaf parents—with that STEM experience in ways that were personally meaningful.

Through photographs and reflections like these, we see the complexity of representation in the museum space. Representations can be explicit—and we know visitors value this—or implicit, and both are taken up by visiting groups as evidence that they do or don’t belong. Where their identities are misrepresented, missing, or feel tokenized within the broader experience of the museum visit, visitors’ sense of belonging is diminished, and they are more likely to see the museum as “not designed for us,” leading to a lack of engagement with or connection to the museum.[5]

Connection to Place

Placemaking may foster a sense of belonging—though groups’ connections to place varied in scale from the immediate physical space of the museum to the broader world. Some groups, particularly repeat visitors and members who had a connection to the museum, described being comfortable in the physical space of the museum, establishing routines and rituals during their visits that reinforced their sense of connection. Other groups appreciated aspects of the museum experience that sparked a more universal connection to place: visitor photos frequently featured models of the Earth that were on display, and individuals described identifying with others and the world.

Iconic nature-scapes or cityscapes also offered moments of belonging. This visitor, like many, described positive feelings of belonging where the museum has connected itself to its larger region/location:

“I like that you have some [city] scenery through these big windows, because I think in terms of belonging that’s what I was thinking about was, like, in the greater world outside of just the museum” (fig 6).

However, some exhibition spaces failed to address the complexities of place and led to negative associations. For example, when an Indigenous visitor saw a map sharing local tribal placenames for regional environmental features, they felt a deeper connection to the museum. But the fact that the map had a small physical presence compared to other designed elements led this visitor to feel a diminished sense of belonging at the same time:

“On the one hand…you’re recognizing that you are on land that did have a different name, and that’s great. On the other hand…a lot about science has also been colonized…so, I was happy to see that there was at least something, but I was very sad that it was, like, literally the only thing…”

Connection to place figures into visitor definitions of belonging frequently enough to support the idea that placemaking is a key strategy for forging connections with visitors, and that, though this connection to place may be sparked by a particular aspect of the museum, it leads to a more generalized sense of belonging across the museum visit.

Comfort in the Physical Space

The physical space communicates belonging through signage (in multiple languages, that uses clear messages to welcome visitors, etc.), through its aesthetics and/or the comfort experienced in it, and through its accessibility (e.g., physical access, affordability, age inclusivity, etc.).

Restrooms, for example, create barriers and opportunities to foster belonging in the physical space. Step stools for children to reach sinks, robust support for people with disabilities, and clear signage welcoming of visitors who are gender nonconforming were often described as moments that mattered to visitors’ sense of belonging.

Physical access can be a challenge across an entire visit, with group members supporting one another’s positive experiences even when encountering a moment that diminished belonging, such as in this group that included a child who uses a wheelchair:

“It was awesome. It was bird eggs from smallest to largest. Except there was no way…you could actually see what was in the drawer.… I ended up taking a picture for him of what was in the drawer. But not every person who goes through the museum has somebody who can take pictures of what’s in the exhibit” (fig. 7).

Visiting groups have different needs in accessing the physical space; universal design principles help us to address this variation through the creation of experiences that are widely accessible. What is clear from the visiting groups that we spoke with is that these principles must be carried across an entire museum visit, as moments of inaccessibility—whether because of language or physical or social barriers—can add up to visiting groups experiencing a diminished sense of belonging in the physical space.

A New Model for Belonging in Museums

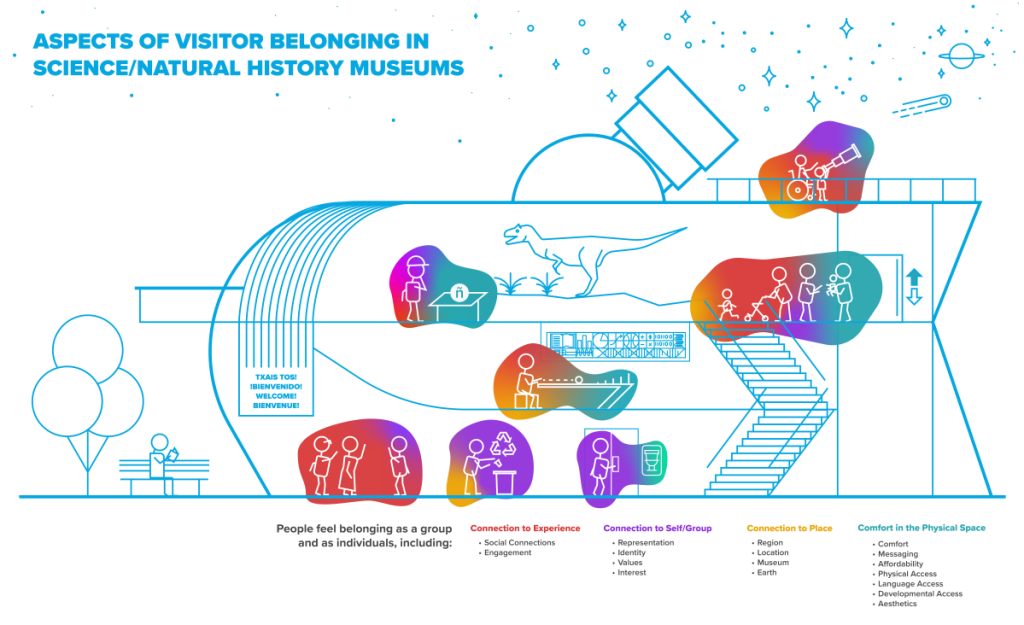

The visitors in our study suggested an expansive definition of belonging that combines identity and agency with the social experience of a museum visit, comfort in the physical space, and connections to place. This definition of belonging is situated in museums and grounded in the lived experiences of visitors with a wide range of identities. It results in a new model that goes beyond an individual exhibit experience and captures the interplay between visitor and museum across the entire visit (fig. 8). The model helps us understand belonging in our museum spaces differently than exhibition-specific or individually focused approaches.

This model shows how feelings of belonging in science and natural history museums are centered in four key and overlapping categories. It also shows how belonging is influenced by both the individual visitor’s and the visiting group’s connections to the experience. Belonging is built in expected and unexpected ways across an entire visit and nuanced because of the range of emotions that contribute to it. Lastly, belonging is actively co-constructed in the physical space and indicates relationships between museums and visitors and among visiting groups. This last point is key for museum experience designers: they must proactively design for belonging and be responsive to what they hear and see from visitors to these spaces.

While we developed this definition of belonging to understand the unique relationship between visitors’ STEM experiences and their visits to science and natural history museums, the interconnected aspects of the visit experience described here—lobby, exhibits, staff-led experiences, cafes/dining options, seating, etc.—are common to other types of cultural institutions as well. The model of belonging that we uncovered, and the priorities it suggests, can be utilized by museum professionals across the spectrum of cultural institutions to reflect on, improve, and design their spaces for belonging.

Designing for Belonging

This article challenges existing ideas about visitor belonging and offers a new definition grounded in the visitor experience. Belonging is more than representation, inclusion, or access on their own; these are the responsibilities that museums have to their public(s), which they must design for and be accountable to. But museums cannot confer belonging on individuals and groups; they must engage in relationship-building with visiting groups, understanding that a visit in which belonging develops is not merely the result of a collection of exhibit experiences, but due to successful placemaking across the entire museum space. At the Science Museum of Minnesota, we have just begun to apply these findings and turn them into actionable change in our spaces.

We have developed a practitioner guide for museum professionals looking to reflect on belonging at their own sites, centered in the definition presented here.[6] We are curious to learn what pieces of this model resonate with museum professionals. We wonder how the voices of visiting groups to other types of cultural institutions echo the visitor voices represented here. We cannot answer these questions yet, but we believe centering the voices of visitors—and acting on those insights to inform changes in museums—deserves continued focus as we work to ensure that all visitors know that they rightfully belong in museum spaces.

[1] Greg Stevens, “Excellence and Equity at 25: Then, Now, Next,” Museum Magazine, July 1, 2017, https://www.aam-us.org/2017/07/01/excellence-and-equity-at-25-then-now-next.

[2] Sandra Bonnici, “Belonging and Equitable Museums,” blog post, American Alliance of Museums, November 22, 2019, https://www.aam-us.org/2019/11/22/belonging-co-creating-welcoming-and-equitable-museums; Tessa Solomon, “As museums move to diversify, newly created roles for inclusion, equity, and belonging take on new significance,” ARTnews, March 11, 2021, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/museum-dei-initiatives-1234586127; and Toledo Museum of Art, “Belonging Plan: Diversity, Equity, Accessibility, and Inclusion Plan. Belonging Matters,” Issuu, August 3, 2022, https://issuu.com/toledomuseumofart/docs/tma_deai-belongingplan_2022/s/16508215.

[3] The findings presented here are from a study supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 2005773. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed are the presenters’ and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

[4] The context of the museum as we describe it includes not only the variety of exhibitions, activities, and amenities that the museum offers on a given day but also the staff and other visitors present and how they interact with the visiting group. Additionally, the museum context is dynamic in that initial moments that matter to visitors’ sense of belonging inform all the moments that follow during their visit.

[5] Emily Dawson, Equity, Exclusion and Everyday Science Learning: The Experiences of Minoritised Groups (New York: Routledge, 2019).

[6] Visit www.smm.org/belonging for more resources on designing for belonging, including the study protocols, webinars, and a practitioner reflection guide.