One major theme of this year’s TrendsWatch report is the inherent fragility of digital records, tools, and services, and the need to plan for the long-term costs of keeping these assets stable, functional, and accessible. (Read the TrendsWatch article “Stop, Look, Think: How to manage digital vulnerabilities” for an overview of these issues, and some suggestions for how museums might respond.) While there are sound guidelines for what a museum should budget for the maintenance and replacement of physical assets like buildings and equipment, it’s harder to benchmark a healthy spending rate for digital. Today on the blog, Nik Honeysett, President and CEO of the Balboa Park Online Collaborative, shares some recommendations on how to approach that challenge.

If you’d like to explore this topic, join me on Thursday, February 27, from 3-4 pm for a Future Chat with Nik. (Free, but preregistration required.)

–Elizabeth Merritt, VP Strategic Foresight and Founding Director, Center for the Future of Museums, American Alliance of Museums

There’s a quote from The Terminator (1984) that, for me, perfectly captures our complicated relationship with technology. In the movie, Kyle Reese warns Sarah Connor about the relentless nature of the Terminator in pursuing her. With a tiny adjustment, it becomes eerily applicable to how we experience technology today:

“Listen and understand. That [technology] is out there! It can’t be bargained with. It can’t be reasoned with. It doesn’t feel pity, or remorse, or fear. And it absolutely will not stop…ever, until you are dead.”

This is technology—a ceaselessly evolving and advancing tool yet utterly integral to our lives. It is how museums get things done, from crafting presentations, to managing collections, to connecting with audiences, to tracking donations. Yet, digital’s relentless march forward can feel overwhelming, especially as artificial intelligence becomes more prevalent. (And we all know what happens when SkyNet becomes self-aware…)

I’ve worked with museum technology since shortly after The Terminator hit theaters. I’ve seen the excitement, the frustration, and the persistent struggle to adapt in the time since. I recall, while working at the Getty Museum in the mid-2000s, proposing a scenario during disaster recovery planning where an EMP (electromagnetic pulse) temporarily wipes out all technology, just like in Ocean’s Eleven. A senior curator became incandescent with joy at the idea of never having to use a computer again. For the next decade, he would ask me when all this “electrickery” might finally disappear.

While we may joke about technology’s pitfalls, the truth is that it’s here to stay. Museums must make their peace with it, learning not just to manage it but to maximize its potential. The real challenge is less in keeping up with technology’s rapid pace than approaching it thoughtfully. This means seeing it as a strategic investment rather than a necessary expense, and as such, one that we must protect, care for, maintain, and replace when it fails to keep up with program and departmental goals. I too often see museums cling to outdated, inefficient tools for years, unwilling to invest in solutions that could transform productivity and engagement. My diplomatic excuse for this is that museums are very loyal to their technology.

When we think about the cost of technology, it’s tempting to focus on the price tag: the expensive software licenses, hardware upgrades, or IT staffing. But the real question is not how much technology costs—it’s what value it delivers. For example, let’s say an application costs $1,000. An expense mindset says that’s $1,000 we didn’t budget for and can’t afford. An investment mindset says that $1,000 saves one employee thirty minutes daily and pays for itself in just a few months.

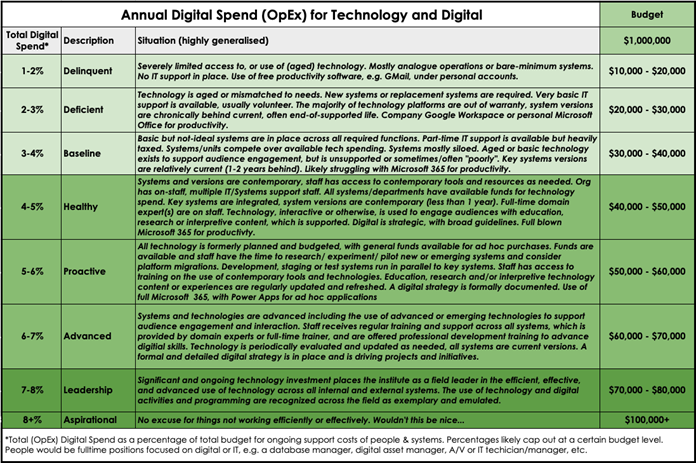

This is where a matrix my colleagues and I have developed comes into play. It’s designed to help museums evaluate their technology spending as a percentage of their overall budget and understand how this spending aligns with their operational maturity and strategic goals. Remember, this matrix is a generalization. If you are spending more, that is great. Focus on the maturity description as your gauge, and whether you are getting value for your investment.

Our benchmarks are backed up by a 2021 survey by Statista focused on the digital activities of museums worldwide. Of the organizations surveyed, roughly 45 percent dedicated no more than 5 percent of their total budget to communication and digital activities, nearly a quarter allocated less than 1 percent, and 21 percent dedicated between 1 and 5 percent.

The matrix outlines eight levels of technology investment, ranging from “delinquent” to “aspirational.” At the lowest levels, organizations spend 1–2 percent of their budgets on technology. These museums typically rely on outdated systems, free or personal software, and minimal IT support—if any. While this may save money in the short term, it often results in inefficiencies, frustrated staff, and missed opportunities to engage audiences effectively.

As spending increases to 3–4 percent, we see organizations at the “baseline” level. Here, basic systems are in place, but they’re not ideal. Part-time IT support struggles to keep up, and systems often operate in silos. This stage represents a turning point: many museums at this level recognize the need for better technology but lack the resources or strategic focus to move forward.

The “healthy” level, with spending at 4–5 percent, marks a significant shift. Systems are contemporary, staff have access to the tools they need, and IT support is robust. At this stage, technology begins to play a strategic role in the organization. For example, digital tools are integrated into audience engagement efforts, and departments have the funds to invest in technology that meets their specific needs.

The “proactive” level (5–6 percent) reflects an organization that doesn’t just react to technology needs but plans for them. Budgets include experimentation funds, and a clear digital strategy is in place. The organization recognizes the value of training to maximize the tools at its disposal, and regularly refreshes digital initiatives to keep pace with changing audience expectations.

At the highest levels we typically see—“advanced” (6–7 percent) and “leadership” (7–8 percent)—technology becomes a hallmark of excellence. These are the museums that my organization cites when asked for exemplars of digital adaptation. Museums in these categories are leaders in the field, operating efficient and effective internal systems and using emerging technologies to engage audiences in innovative ways. They support staff with ongoing professional development and integrate technology into many aspects of operations. These organizations demonstrate what’s possible when we see technology not as an overhead cost but a driver of mission fulfillment.

Finally, there is the “aspirational” level—wouldn’t that be nice?—where spending is 8 percent or more. Few museums achieve this in reality, but it represents a vision of technology as a fully integrated, highly efficient force multiplier. Here, systems work in harmony, and the organization’s digital activities are recognized as exemplary.

This matrix is less of a rigid framework and more of a guide to help museums understand where they are and what it might take to mature and advance. The key takeaway is that we should view spending on technology as an investment—not just in systems and people but in the museum’s ability to fulfill its mission, engage its audience, and remain relevant in an increasingly digital world.

As with any category of spending, we must account not only for the cost of acquiring digital tools but maintaining them over time. While the relentless cybernetic assassin of The Terminator is thankfully fiction, the threats to museums’ digital assets are very real. We face several unavoidable depreciation challenges, one of which is “bit rot”—the physical corruption of data over time. (Think of it as the digital equivalent of a painting slowly fading under the sun, except instead of colors dimming, entire files or systems can disappear into oblivion.) The other is “data decay”—the depreciation of the value of our data over time; for example, an out-of-date member address or email.

So, how might museums plan for the ever-present march of technological change and mitigate these challenges? Once again, this will require a change in mindset. Museums are often more comfortable funding new initiatives than maintaining old ones. However, digital sustainability isn’t just about keeping things running; it’s about ensuring access, usability, and relevance for future generations. When making the case for long-term digital investment, we should frame it as an extension of the museum’s core mission to preserve and share knowledge. After all, bit rot and platform obsolescence are the digital world’s equivalent of losing an artifact to time.

OK, here’s my last pop-culture reference. In Minority Report, the future is predicted through data and technology. While we don’t have pre-cogs guiding us, our strategic investments in technology today can help us shape a future where museums thrive, adapt, and continue to connect emerging audiences to our programming and collections on their digital terms.

Brilliant article, Nik. I love reframing how and why digital transformation should take place as a way of persevering and building for future audiences rather than a necessary evil.