On occasion, I use this space to comment on norms and practices that I feel do active harm to our sector and our peers. (See, for example, my short rant on “quiet quitting” and the pernicious effects of workplace heroism.) Today I’m going to share some thoughts that have been percolating for some time and brought to a rolling boil by recent events.

Here’s my thesis: Efficiency is over-rated.

The inflated value of efficiency originated from the for-profit sector, but in what we might call “metric creep” has inched over into the nonprofit sector, including museums, in pernicious ways. It’s often a destructive driver of performance for companies and corporations, and doubly so for our field.

Corporate efficiency experts often swoop in declaring they are there to “trim the fat.” To paraphrase Inigo Montoya in the Princess Bride, I don’t think that analogy means what they think it means. Body fat is a complex human organ that is essential for health and longevity. Fat is our energy bank, a key moderator of chemical and neural signals, essential components of our immune systems. And when I fall on my keister, I for one am happy to have a little padding.

Similarly, things efficiency mavens might tag as redundant may in fact provide a much-needed safety margin. Extra stock of critical supplies; staff enough to cover for colleagues as needed; time enough to spend with clients, customers, or co-workers forming much-needed social connections.

Sure, there are processes I want to be efficient: renewing my car registration, updating my computer software, having a tooth extracted. But even some everyday inefficiencies, like slow checkout lines in my local grocery store, can create serendipitous moments of connection.

I get why businesses often fetishize efficiency: it can minimize short-term costs (notably staff salaries) and maximize short-term profits. And profit is the most important metric, right? After all, economist Milton Friedman flat out declared that the only responsibility of business is to increase its profits. With that goal, companies may pursue efficiency by squeezing every minute of work possible out of employees, eliminating redundancies, and streamlining processes.

But this relentless pursuit of efficiency is a questionable long-term strategy even for profit-driven companies, because efficiency is also fragile and prone to disruption. When the COVID-19 pandemic struck, hyper-efficient “just-in-time” supply systems collapsed. Companies with “just enough” staff were unable to perform essential work if even a small percent of the workforce was out sick. Because vaccine production was “efficiently” centralized in just a few plants across the globe, breakdowns or slowdowns resulted in preventable deaths.

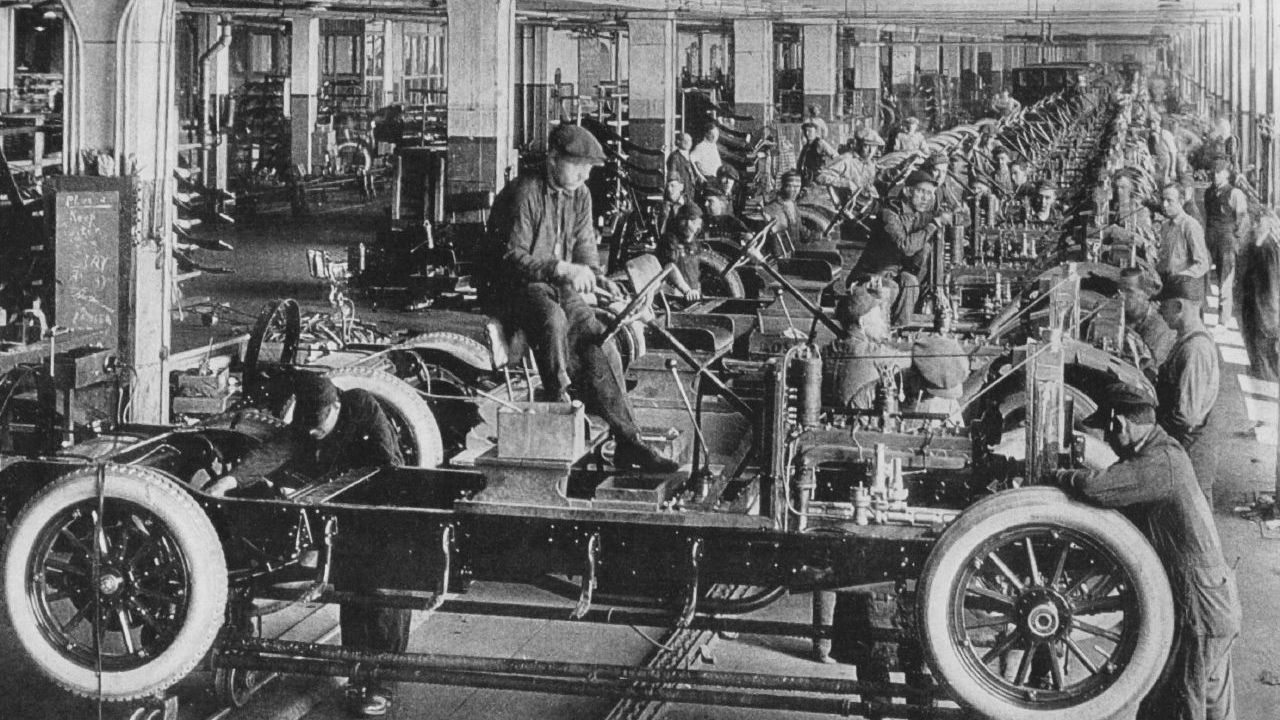

Frankly, I want my essential services to be effective, robust, and resilient. For example: health care. It is unquestionably more efficient (and profitable) for practice conglomerates to expect their doctors to see four patients an hour. Which puts the burden on me, the patient, to triage my problems, making a lay judgement about which may be hints of something serious enough to kill me without a doctor’s attention. It may be efficient to group students in age cohorts, sit them at desks, and feed them all a standard curriculum. I think we would better serve our children, and our society, by taking the time and resources to provide education tailored to individual strengthens, passions, and modes of learning. (I highly recommend taking 11 minutes to watch Sir Ken Robinson’s classic TED talk on how the efficient “production line” model of modern education is failing our kids.)

The campaign for efficiency often demonizes “inefficiency,” but that’s a straw man. The inverse of efficiency isn’t inefficiency; it’s effectiveness. To be effective, a doctor may have to spend a half hour or more building rapport with a patient, conducting a thorough exam, asking questions that elicit a context for a diagnosis. To be effective, a teacher may need to give more time and attention to students facing challenges. The education system may need to shift to prioritize experiential learning over seat time.

This distinction, between efficiency and effectiveness, is particularly important for museums. Is the most important metric throughput (how many people we move through our doors, and how quickly)? By that measure, the Mona Lisa gallery at the Louvre is killing it. (Oh, wait, it’s not.)

But museum people know it’s not just about number of visitors—the quality of experience, the impact on a visitor, emotional or cognitive, is the greater measure of success. But visitation is an “easy” metric, one often valued by boards and by funders. Impact, however superior is harder to assess. That’s why the Alliance is working hard to make it easier for museums to measure and report on social impact—the well-being of people around them.

Efficiency isn’t a great metric for museum staff, either. In a sector already suffering from burnout, and struggling to attract and retain the people we need to do good work, why would expecting people to be “productive” every minute of the day be a good strategy? (See aforesaid rant on quiet quitting.) I’ve long been an advocate of programming no more than 90% of staff time, max. That other 10 percent? It’s space to think and plan, it’s a source of resilience and renewal, and it provides room for creativity even in jobs that aren’t explicitly devoted to creative output. It’s room for human connection with the people we serve, and for letting people be seen and valued. The bodies of knowledge that museums exist to preserve and share—art, culture, the scholarship of history and science—depend on time and mental space to think, dream, experiment, create, and fail, over and over again. Should not museums embody those values as well?

While I’m at it, a few remarks about a related concept, “scalability.” The ability to scale a project is another metric worshipped in business, particularly in the tech sector. And for the tech business model it makes sense: invent once, deploy at scale, maximize profit. But, like efficiency, scalability as a metric devalues many of the things that museums do best. If a museum has a great online curriculum, should it try to ensure it is known, and used, as widely as possible? Sure! But many of the best museum programs are place-based, hyper-local, tailored to the needs of specific parts of their community–that’s grand as well, and may well result in a beneficial outcome that no other organization could produce.

One of the most delightful museum projects I ever came across was the 2010 Live Music Soundtrack by Machine Project at the Hammer Museum, in which two resident guitarists were available to walk visitors through the galleries, improvising music to the art they encountered. The real life experience was not even scalable to all on-site visitors. Could museums provide an app with a prerecorded playlist instead? Yes, they could. They could even enlist Spotify to generate algorithmically personalized selections. But frankly that technology is less magical than being trailed by a musician whose electric guitar is plugged into your headphones. A scalable digital simulacrum might be fun in its own way, but it would strip out the human connection we so desperately need. If that anecdote seems a bit arcane, consider first-person interpreters—far more common, and often creating equally wondrous encounters. I doubt that AI-powered chatbots, even trained on sound historic data, can create the same quality of connection.

Rather than imitating their for-profit brethren, I believe nonprofit museums can lean into their strengths. Yes, museums need to balance the books, but, not being beholden to stockholders, they can prioritize effectiveness over efficiency, impact over the financial bottom line. They can provide space and time for open-ended, personalized interactions with the public that have no clear goal. Now, more than ever, it is important for museums to be willing to buck conventional wisdom, speak truth to power (or funders), and quietly hold themselves up as an example that businesses might want to emulate, if all sectors—government, for-profit and nonprofit—are to work together to build the world we want to leave to future generations.

Great blog Beth,

Excessive commitment to efficiency both stifles creativity and increases risks to both sudden events, think hurricanes and wild fires, and gradual changes like shifting public interests. We need to keep not just a safe, but a healthy, distance from our noses to our grindstones.

Rob