Two years into his work, an editor at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago reflects on the institution’s bilingual transformation.

This article originally appeared in Museum magazine’s March/April 2025 issue, a benefit of AAM membership.

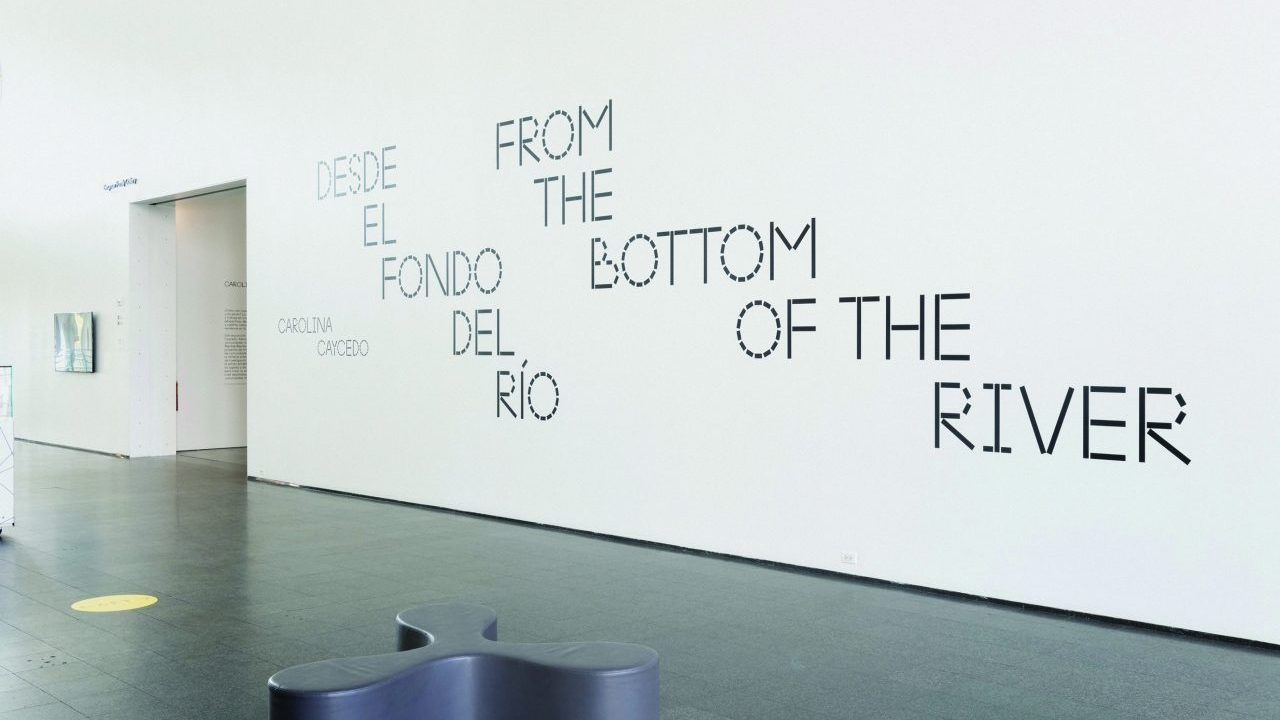

On the last day of the exhibition “entre horizontes: Art and Activism Between Chicago and Puerto Rico” at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in Chicago, on display from August 19, 2023, to May 5, 2024, I found myself alone in Chicago’s downtown—a rare occurrence for me. Walking along the shore of Lake Michigan, Bomba Estéreo playing in my earbuds, I suddenly felt I was in Latin America.

The shorefront could have been a busy beach in Viña del Mar, Chile, my home country, or el malecón in Havana, or even South Beach in Miami. Families and tourists strolled along the sunny lakefront, friends played volleyball, and college students lounged, drank, danced, and sang along to music by Bad Bunny, Taylor Swift, or Kendrick Lamar.

Like many museum professionals, I don’t usually spend my days off at my workplace. But I made my way to the MCA to see the exhibition “entre horizontes” because I felt entre horizontes, or between horizons—not in the United States nor Latin America but somewhere in between, or in a constant state of translation.

In 1964, a group of collectors, art dealers, artists, art critics, and architects united around a shared belief that the people of Chicago deserved a contemporary art museum. Founded in 1967, in a converted building once home to Playboy magazine’s headquarters, the MCA began as galleries for avant-garde art. Its current larger space, completed in 1996, offers galleries, a theater, educational facilities, administrative offices, gift stores, and a café named after the Venezuelan artist Marisol. Over the decades, the MCA has become renowned for supporting the local arts scene while also presenting global and contemporary art and performance.

In 2027, the museum will celebrate its 60th anniversary, a milestone to reflect on the MCA’s founding vision. What kind of museum do the people of Chicago deserve? Like in the 1960s, Chicago is a diverse city. Today, the population is about equal parts white, Black, and Latino, with a smaller yet equally rich Asian population and a myriad of other cultures, languages, and worldviews.

This diversity mirrors a larger national shift toward multilingualism and cultural pluralism. According to the Cervantes Institute, the US is on track to become the second-largest Spanish-speaking country in the world by 2060. Will US museums ignore this evolution, or will they, like the MCA Chicago, embrace bilingualism?

The Bilingual Initiative

“entre horizontes” made history for the MCA. It was the first exhibition where all galleries featured side-by-side English and Spanish labels. Two years before the exhibition, the museum launched its bilingual initiative to translate exhibition labels, supplemental materials, and other visitor resources into Spanish. That’s where I, the first Latino and Spanish-speaking editor, entered the picture. I joined the MCA to ensure Spanish translation is thoughtfully implemented and respected.

The main impetus behind the bilingual initiative is to improve access for the Spanish-speaking visitors from Chicago, the US, and other countries. More specifically, we want the Hispanic-Latino population of Chicago (28.8 percent and growing, according to the US Census) to feel that this is their museum, even if for a long time it didn’t quite speak to their lived experiences.

“entre horizontes” taught us how to incorporate translation in a meaningful way: what to repeat and what to avoid, how to translate already bilingual titles, and how to “translate” cultural and artistic efforts for different audiences—programming for Chicago’s Puerto Rican community is different than what we would create for, say, Italian or Chinese tourists.

We also sought feedback on how the public was reacting to this new MCA. A focus group made clear that we had focused too much on the art: we realized that for visitors, translating a label is as important as, for example, translating the bathroom signage. You need both to fully experience the museum, don’t you?

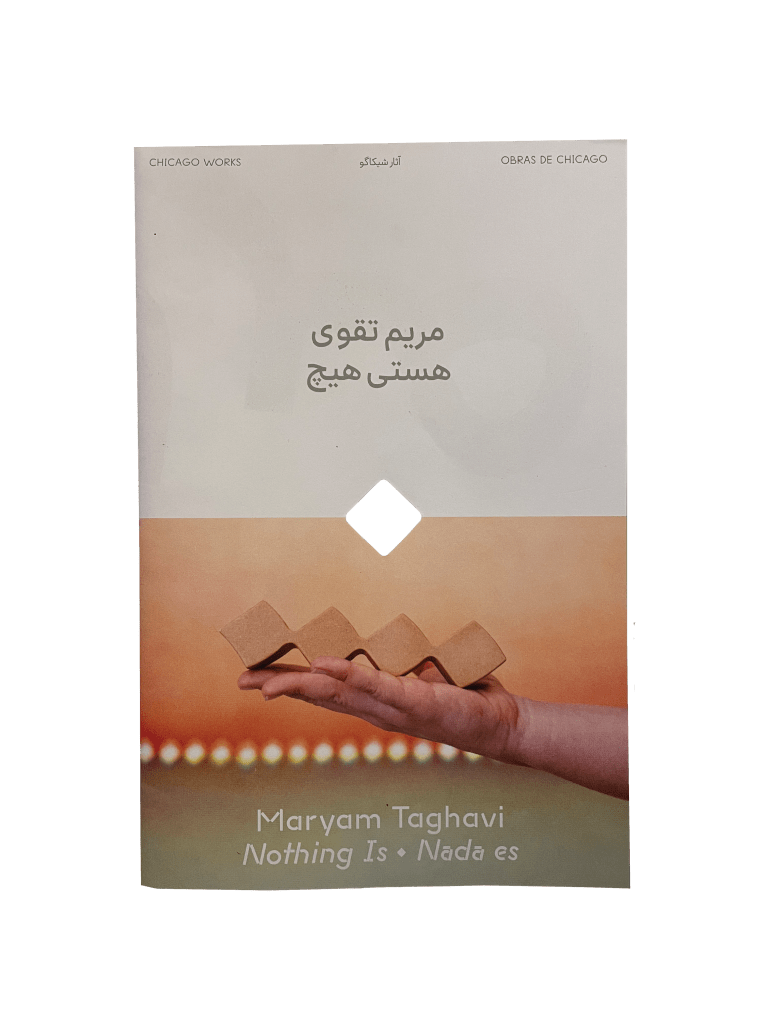

Since then, we’ve occasionally incorporated a third language. For example, an exhibition featuring artworks by the Iranian artist Maryam Taghavi, which opened in December 2023, included Farsi translations in addition to Spanish and English. We produced a beautiful, trilingual folding pamphlet and translated the press release into Farsi.

With this exhibition, at least two things became clear. First, we must be intentional about translating into a third language. Simply because the artist is from a certain place or culture does not mean the museum should translate into that language, unless that is the artist’s intention. In the Taghavi exhibition, the artist used dots and many other linguistic marks to explore the limits of language. In fact, a big element of the exhibition was the noghte, the most essential diacritical mark in Persian and Arabic. Secondly, trilingual exhibitions require additional time and resources. Inclusivity can’t come at the expense of overworked museum staff. Museums and cultural institutions must put their money where their bilingual or trilingual mouths are.

The Why of Translation

Since joining the MCA, I have learned that translating a museum has different challenges than, for example, translating a book or movie subtitles. Museums need to balance complex ideas with accessibility when translating art while also being straightforward with informational materials and wayfinding signage. Also, translations push you to rethink the institutional voice.

How do you want the museum to speak to visitors in Spanish? The same as English? Younger? Formally? Are you including Spanglish?

To address this, I am developing guidelines, resources, and methods, including a Spanish style guide that mirrors our English one. This guide will cover grammatical usage in Spanish (¿usted o tú?) and include a section on the history of Spanish in the US and Chicago, one of the few places you can find the Spanish dialect known as MexiRican.

Additionally, for the past year, I have been drafting a translation statement for the MCA that highlights the role of translation and the translator—not just in our museum and in the contemporary art world but how it aligns with other similar practices in society. The MCA’s translation statement will include these five guiding ideas, among others.

- Museums are already translation zones. Translation—the movement between languages and cultures—has always been integral to museums. Artists communicate through visual, digital, intertextual, and hypertextual languages. Curators translate these into written language for museum labels. Such processes bridge diverse systems of meaning—just like going from English to Spanish.

- Words signify worldviews. Museum labels are more than informational—they reflect perspectives. Incorporating languages beyond English can broaden access and challenge monolingual worldviews, perhaps even lead visitors to question the notion of “American exceptionalism.” With translation, the MCA can move from the comfort zone of English monolingualism in its galleries to a new semiotic landscape that reflects the complex linguistic and cultural realities of Chicago, the US, and the globalized world.

- Translation sustains societal connections. By emphasizing translation, a museum can acknowledge its role in broader society: children translating for immigrant parents or interpreters aiding refugees. By incorporating translation as a visible practice, the MCA is highlighting how it sustains daily life throughout society.

- Artists interrogate linguistic dominance. Many artists, like Croatian conceptualist artist Mladen Stilinović in his work An Artist Who Cannot Speak English Is No Artist, use text in their art to highlight the ways language shapes perception and enforces power structures. Museums should embrace these critical explorations, engaging with art that expands on themes such as migration, diaspora, and identity.

- Translation sharpens our language use. It invites us to question words and concepts we take for granted. For instance, what does “America” mean to someone in Chicago’s mostly Mexican neighborhood La Villita versus someone from Oklahoma City? Is America a country or a continent? Translation encourages audiences to question things they may take for granted and reflect on more than one viewpoint.

In my two years at the MCA, I have connected with colleagues from across the country, the continent, and the globe who often ask me how their museums can more intentionally incorporate translation. This question always brings to mind one of my favorite English expressions: lost and found. In Spanish, we are less optimistic about that place where lost items are waiting to be found by their owners. We use the term “objetos perdidos,” lost items, as if those things were already—and sadly—gone forever.

With the help of translation, museums can become a gigantic lost and found—a place where audiences are encouraged to lose themselves (and maybe some of their preconceived ideas) and find or gain something about themselves. At the MCA, translation not only enhances accessibility but also deepens the sometimes confounding, and always mesmerizing, exploration of identity through contemporary art.

Sidebar

How to Start Translating in Your Museum

Frame your linguistic approach. Translation might initially seem like an easy task, especially with the internet and artificial intelligence. But consider a conceptual frame as well as a strategy before you start. Why and how are you translating? What are your short-, mid-, and long-term goals related to translation and accessibility? Can you afford an in-house translator, or will you outsource everything?

Hire the right people. Decisions about a language should not be made by those who can’t speak those languages. A museum that truly and holistically wants to expand its linguistic appeal should empower underrepresented groups and/or the people with expertise in those languages. Otherwise, you risk simply ticking a box and not fostering discourse around a social issue that can bring visitors to your museum.

Create programming around translation. Once you incorporate a language that is not English in your galleries and materials, consider how to amplify this linguistic addition through complementary programming. In 2024, for example, the MCA organized a panel on the connections between reggaetón and contemporary art in partnership with the Instituto Cervantes Chicago and Sueños Music Festival. The panel was in Spanish with simultaneous English translation. That’s another key element of a bilingual institution: not everything has to originate in English.

Find out what your peers are doing. The Pérez Art Museum Miami is almost fully bilingual (Spanish and English) and offers many materials, resources, and programming in Haitian Creole. Museo de las Américas in Denver, the Museum of Chinese in America in New York City, and the ‘Iolani Palace in Honolulu, Hawai‘i, are other institutions with bi- or multilingual approaches.

Partner up! In June 2024, “Akito Tsuda: Pilsen Days” opened on the ninth floor of the Harold Washington Library Center, part of the Chicago Public Library system. This trilingual (Japanese, Spanish, and English) exhibition features work by Japanese photographer Akito Tsuda highlighting the spirit and daily life of Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood in the 1990s. For this exhibition, the Chicago Public Library worked with the Japan Foundation and the Terra Foundation for American Art. Translation offers not only an opportunity to share costs but also a chance to build meaningful institutional partnerships.

Captions and Credits

Photo by Nathan Keay © MCA Chicago

Page 18

A mural by artist Rafael Ferrer for the exhibition “entre horizontes: Art and Activism Between Chicago and Puerto Rico,” which ran from August 19, 2023–May 5, 2024.

© MCA Chicago

Page 21

Bilingual materials for Family Days at the MCA Chicago.

© MCA Chicago