This article first appeared in the journal Exhibition (Spring 2025) Vol. 44 No. 1 and is reproduced with permission.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) in museums is nothing new—we’ve seen iterations of it in exhibitions for almost a decade. Science museums have primarily focused on using exhibitions to establish what AI is (and is not), to forecast its potential, and to explore its social intersections. Art and culture museums have leveraged AI thematically, often in conjunction with other emerging technologies, to create dialogue on the evolving meaning of humanity. AI has also been a fascinating exhibition tool, with museums and science centers using it to animate content and enhance visitor interaction.[1] In 2023, the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University notably tasked AI with curating an exhibition, thus using it as both a tool and a foil, spotlighting AI’s power and limitations.[2]

Since ChatGPT launched in late 2022, it has been changing how we work across many industries and sectors, and museums are no exception. ChatGPT is evolving but, in essence, it is an AI chatbot that leverages machine learning and natural language processing, which together allow it to generate human-like text, code, and images in response to user prompts. While generative AI (GenAI) products such as DALL-E and Midjourney[3] had been on the market since 2021 and mid-2022, respectively, ChatGPT’s rapid adoption by museum professionals across almost every discipline amplified curiosity and concerns. In exhibitions, the conversations around AI usage became more urgent and, frankly, more interesting. With a free version that seemingly offered help on everything from idea generation to writing to translating (and this was before ChatGPT’s image-generation capabilities), ChatGPT’s utility was quickly recognized by content producers and other exhibitions professionals as both a support tool and potential perpetuator of systemic biases and misinformation. Exhibitions tell stories and design experiences for public consumption—when AI plays a role in their creation, the responsibility for ethical use reaches far beyond job displacement and intellectual property to fairness, privacy and security, environmental impact, and more.

Technology adoption curves break down users into five primary groups: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards, showing the proportion of users who fall into each segment (fig. 1).[4] While individuals belonging to each category experience differing motivations and comfort with risk, the spread of an idea (or, in this case, technology) is influenced by the adopters themselves as well as factors such as compatibility, ease of use, and economic and infrastructural considerations.[5] These last two factors (cost and facilitation) have typically kept museums and other cultural nonprofits behind the curve when compared to, say, enterprise or even the government and education sectors. An apt case study may be augmented reality (AR): When did you first notice the computer-generated first down line in a televised college or professional American football game, or the offsides line in an (actual) football match? Compare this to when you first encountered AR in an exhibition. Additionally, within museums, interest in the applications of a given technology can be somewhat diffuse, championed perhaps by a small group within a single team; for example, exhibitions’ promotion of immersive projection systems, operations’ or membership’s interest in data lakes (centralized data processing and storage), or education’s interest in learning management infrastructure.

AI is different. First, across units, in AI’s free (or mostly free) incarnations—ChatGPT, DALL-E, Midjourney—museum professionals have quickly noticed its potential to alleviate workloads and/or support administrative and creative task completion. Second, the sector’s concerns over and responses to the ethical implications of AI collectivized. The widespread availability of AI tools effectively de-siloed us: museum workers recognized that, across individuals and teams, new debates, resolutions, and responses were needed if we were to continue building trust with our visitors and stakeholder communities. While prior to 2022, AI and other emerging technologies appeared “high barriers,” AI’s sudden affordability and accessibility meant that we urgently needed frameworks for operating, communicating, and using these tools.

Consumer-facing tools like ChatGPT and Midjourney require large datasets (i.e., the internet) to generate responses, and whatever data you might find running a search on Google is readily available to the underlying large language model.[6] While this dataset is vast, the quality of that data varies dramatically, and GenAI tools aren’t necessarily filtering for accuracy. While these tools are often effective, their convenience and low cost comes with legitimate concerns about bias, ownership, citation of data, and inaccurate results called hallucinations.[7]Additionally, questions about the long-term implications of AI development are compounded by the rapid rate at which the industry is changing. Initiatives such as Stargate appear to coalesce power and investment around a few central players within the tech sector while smaller teams such as DeepSeek are generating new revelations about computational power, cost, and ownership.[8]

With these observations in mind, we (the authors) embarked upon a project aimed at better understanding whether and how museum professionals are currently engaging with AI as an actual tool that yields work products. We are further interested in elucidating how the technology is integrated into individual and institutional workflows and processes. The project additionally examines what skills museum workers believe they need to leverage AI and other emerging technologies. As a corollary to professional development, we want to identify whether and how museums and institutions are preparing to guide their employees’ interactions with AI. With the cascade of legal implications AI has for intellectual property, human resource management, and technology investments, we ask:

- How should we talk about AI ethics?

- Who has decision-making authority over AI usage within organizations?

- How should consistent practices and guidelines be established, and by whom?

State of the Field

To begin to address these questions, we conducted an on-site survey during the 2024 science education and communication conference, Ecsite, in Ljubljana, Slovenia. The majority of the attendees and, thus, survey respondents, represented museum and science-center professionals based primarily in Europe, but representatives from North America and Asia-Pacific were also included. Over the course of a week, we collected responses to a single question:

Are you currently using AI and, if so, how?

Attendees of our workshop, “AI for Career Growth (It’s Not Just Your CTO’s Problem Anymore),”were prompted to take the survey, and, additionally, it was broadcast to all registrants of the conference using the conference app.

Of the 81 answers we received, 89 percent of our peers indicated that they are indeed using AI and predominantly for professional purposes; only 11 percent of survey participants said “no.” Furthermore, almost 55 percent of the 72 positive responses specified that they were using AI to support tasks such as research, writing, project management, and experience development—work areas that directly integrate with exhibition development and exhibition-making (fig. 2).

These work areas may be generally categorized as a) workflow optimization and b) content creation. While these data may skew geographically and toward those with inherent interests in AI and technology, they do represent a provocative path of inquiry that we are continuing to pursue.

So, how do we overlay “AI ethics” onto “AI in museum exhibitions?” At the same conference, we led workshop teams through facilitated discussions on their professional use of AI, focusing attention on how and where they anticipate the tools intersecting their museum work. We then asked the participants to identify questions critical to operational and ethical deployment of AI in the workflows and processes they surfaced. While we used an imaginary informal science institution as a case study subject for the workshops, the outputs can be applied across museums of all disciplines, particularly as our moderators and participants represented professionals from research, culture, education, and the arts.

Figure 3 shows the tasks that AI can support in museum work, as identified by our workshop participants. The broader categories—administration, experience, and content—should be particularly familiar to members of exhibition teams, who are intimately associated with the latter two work areas and unlikely to be able to avoid the first. As such, we are able to ask:

How do ethics, rather than legalities, interact with these objectives?

Framing Ethics for Museum Exhibitions

When participants were tasked with identifying critical questions in AI usage, they collectively focused on ethics, particularly as it pertains to engagement with external stakeholder communities. It is worth noting that we deliberately avoided using the term “ethics” during this workshop, preferring to let participants converse without constraints. The important and urgent questions the teams identified concerned:

Privacy and security of collected data. With museums collecting visitor data through exhibition experience interfaces, ticketing kiosks, and online interactions, what safeguards are in place to protect these data from being hacked and hijacked?

Transparency of museum processes that use that data. Once museums are in possession of visitor and audience data, how, where, and when are the data being used and to what end? Will the data use net benefits for visitor experience or potentially cause harm through profiling?

Biases in datasets and data processes that promote discrimination and harm against communities. GenAI tools ingest data by “scraping” the internet and from user inputs, thus making them vulnerable to systemic biases, conflicting data, opinions, and conjecture.[9] How can museums leverage AI tools without perpetuating harm and misinformation? (The familiar adage “garbage in, garbage out” understates the potential damage in these instances.)

Overwhelmingly, the concerns voiced by workshop participants centered not on whether museum workers would be replaced by AI, if it was “right” for museum workers to use ChatGPT to generate labels, or copyright infringement, but instead on how use of AI tools may lead to the erosion of audience and community trust. This anxiety is perhaps even more pronounced for two reasons: first, some of the most compelling opportunities identified by participants for using AI pertain directly to creating meaningful and accessible visitor experiences in museums—exhibition personalization, reaching underserved communities, depolarizing exhibition content—and so hyperawareness of the need to safeguard against AI doing the exact opposite was particularly evident. If, for example, experience personalization relies on collected visitor data and AI, this interaction is dependent upon the large language model (LLM, the machine-learning models that process textual data to generate human-like responses) of the AI; thus, if the LLM is created without safeguards or moderation against erroneous responses or hallucinations, then there is also no control over the generated output. Second, almost every participant in the workshop was already using off-the-shelf AI solutions (such as ChatGPT, DALL-E, and/or Midjourney) rather than homegrown applications, which would have a greater likelihood of giving their users at least some degree of oversight into the data ingested and the processes and algorithms that use it.[10]

Workshop participants additionally highlighted the importance of stakeholder inclusion in supporting AI usage and implementation in experience-focused practices. In particular, participants noted that children and their caregivers were frequently absent from museum working groups and task forces on technology deployment, despite this group’s status as a core audience segment for many museums. Donors and board members, external collaborators such as artists and scientists, and “minority visitor groups” (e.g., the elderly) were also identified as MIA stakeholders. Three provocative and related questions were raised in these conversations:

- How and when do we manage stakeholder time and commitment (when in the process should they be engaged)?

- How do we recognize AI expertise?

- What new challenges does this present for evaluation teams?

Museums must ensure quality of data inputs and accuracy in AI-generated outputs to maintain trust with their audiences. While software developers are addressing this, AI adoption is outpacing standards (assuming these exist and are enforceable) for content validation. Institutions can solve for this conundrum by creating custom databases to reduce bias and through dedicated oversight of the processes that interact with the data, but, for cultural institutions, this approach is new and potentially costly, requiring time, staff training, and/or external support.

Museums are in a transition phase: We don’t yet have practices for involving audiences and stakeholders meaningfully in the development of AI content and operational pipelines. However, we believe that institutions can take a first step by forming AI task forces that segment and engage stakeholders on a case-by-case basis, with the end goal of identifying ethics-driven frameworks and policies.

Ethics and Education: Training Staff for the Present and Future

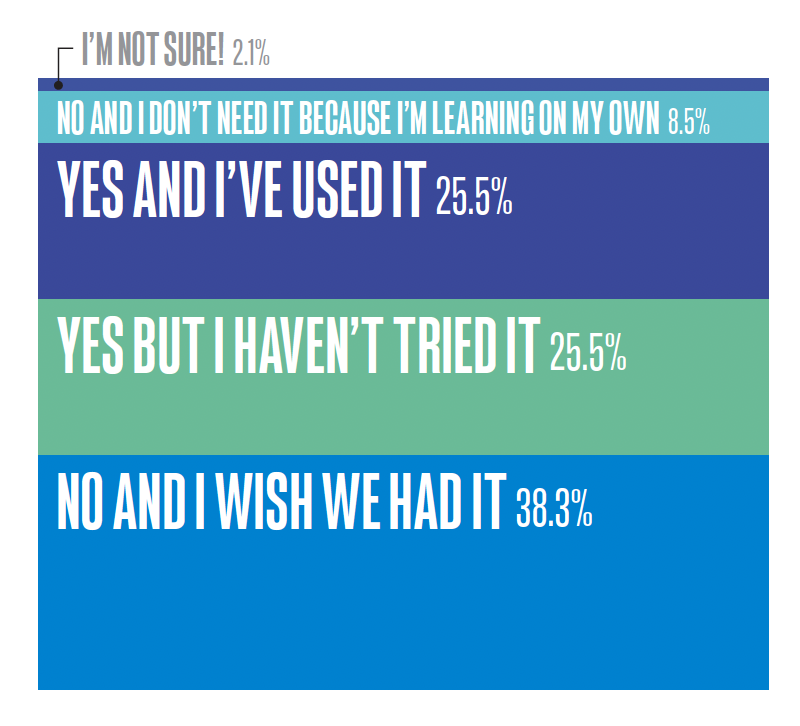

At the Ecsite workshop already mentioned and at ASPAC 2024, we polled 48 museum professionals on whether their employers provided any professional development opportunities specific to AI. More than 50 percent of respondents answered in the affirmative; however, half of those who said “yes” noted that they have not yet participated in those training opportunities (fig. 4). While their reasons for sitting out this professional development are unknown, various priorities competing for their time and attention is a likely factor. Tellingly, as of 2024, 38 percent of respondents did not have AI training available to them through their employer but wished otherwise, while nearly 9 percent have taken AI education upon themselves in the absence of employer support.

These data suggest that museum leadership is well positioned to make meaningful investments in employee upskilling around AI, a tool that many, if not most, employees are likely already using. Furthermore, museum leaders are ethically obligated to establish best practices and policies on how their colleagues engage AI and how such technologies impact their visitors, audiences, and stakeholders.

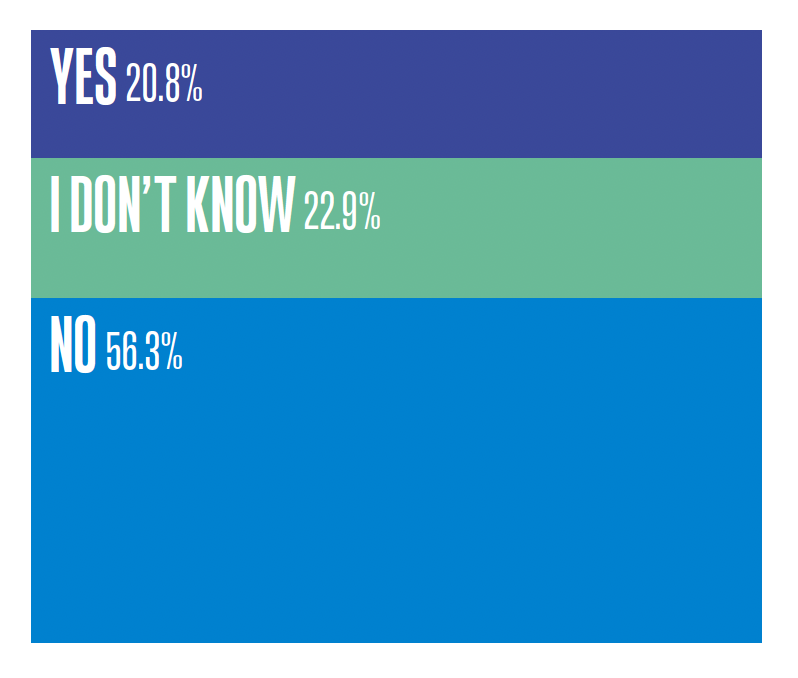

This same group of survey respondents were then asked whether they were aware of a data and/or governance policy on AI at their institutions (fig. 5).[11]

Here, only 21 percent of the 48 respondents indicated “yes.” The “nos” (56 percent) and “don’t knows” (23 percent) suggest that, institutionally, museum policies are lagging quite far behind their employees’ AI usage needs. (In upcoming studies, we seek to understand how cultural institutions can support AI usage after these individual-level workflows have already been established.)

The discrepancies between employee needs and institutional investment and preparedness may be particularly noteworthy for exhibition teams. As mentioned above, many of these professionals rely frequently on off-the-shelf AI solutions, which are frequently “black box,” meaning that their inputs and processes are not visible to users. While AI implementation frameworks may competently serve teams that have some oversight into data extraction, transformation, loading (ETL) pipelines, or algorithmic building processes, ready-made products may be especially vulnerable to those biases that our workshop participants surfaced, as they ingest and process data from sources and with means that are deliberately opaque.[12] Users then may unintentionally participate in and even contribute data to systems that are, at best, ignorant of the systemic biases they cause and, at worst, sacrifice citizen privacy, security, and well-being for financial gain.

Notably, when workshop attendees were asked to identify areas for AI-focused skills development in free-form breakout team discussions, none of the teams surfaced technical training and know-how (such as being able to write machine-learning code) as opportunities for professional development. Instead, knowledge-building and knowledge-sharing on critical thinking skills and ethics were their professional development priorities. While our study is ongoing, these early outcomes suggest that museum leaders are strongly positioned to focus on two AI-related priorities:

- Leadership should engage employees at all levels to identify current usage, competency, and interest in AI, with an end goal of building professional-development programs and pipelines that serve both the employees and the institution’s human resource growth and retention strategies.

- Museums and cultural institutions must bring together both internal (staff) and external stakeholders to structure frameworks and policies that govern the use of AI and other emerging technologies.

This latter investment is not only necessary and ethical but also reinforces engagement from what we can agree is the most important resource any institution supports: its talented staff.

Charting an Ethical Course

Things are moving quickly. Within the past year, OpenAI (maker of ChatGPT) has raised $6.6 billion in funding and has a central role in the Stargate initiative.[13] The Nobel Committee, not without some controversy, awarded the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physics to Geoff Hinton and John Hopfield for their work contributing to the development of neural networks.[14] Companies and startups are competing vigorously to capture the top spots in artificial general intelligence (AGI), a subset of AI that seeks to capture and replicate human-like cognitive capabilities.[15] Museum visitors and professionals are highly attentive and knowledgeable (even experienced) in this technology: How might we, as exhibition and experience producers and museum professionals, capture this momentum and invest in infrastructure, knowledge banks, and governance policies for AI? Policymaking is a particularly critical area to watch, as governments develop and publish AI bills of rights and related policies to catch up with technology evolution.

The prevalence of affordable AI tools accelerated the museum community along the technology adoption curve. A large majority of museum workers appear to be using AI in some capacity or another to assist their current work and see the potential for enhancing visitor service and interactions through AI. This rapid adoption presents an unprecedented opportunity for museums to establish strategies and strategic investments not only in response to AI needs but also other emerging technologies. As our audience and stakeholders grow more savvy, museums must also evolve to promote their services and relevance.

Can museums trust the developers of GenAI technologies to determine best practices and content validation? While museum staff likely have the best interests of their organization in mind, the technology is already in use, ad hoc, and individualized. Museums need to engage meaningfully with AI, starting with leadership, to ask questions about its ethical and practical value and to determine the best path forward. This conversation isn’t entirely unfamiliar. There are precedents—large and small—such as institutional presence on the internet, visitor trust and the use of Adobe Photoshop, QR code adoption, the ongoing dialog around cell phone usage in exhibition design, and so on.

Ignoring AI won’t make it go away and won’t answer legitimate questions about ethics, bias, opportunities, and trust. Finding an active path forward that engages with GenAI tools and shapes their usage depends on museums doing the research, evaluation, and prototyping that we already apply in other areas.

What We Should All Be Asking

- Do I need AI?

- Evaluate whether AI needs to be integrated into your existing or future workflows—where and why?

How Leadership Can Support Ethical AI Usage

- Work with employees across museum departments to understand current AI (and other tech) usage and needs.

- Engage with content teams to determine skill gaps and opportunities for specialized training. Provide time for subsidized AI-focused learning and ethics. Options range from single workshops to certification courses.

- Form a working group to engage visitors and communities on your data processes, including how their data is currently used and why, and how it might be used in the future.

How Exhibition Teams Can Support Ethical AI Use

- Distinguish between AI usage that requires oversight and usage that would benefit from best practice guidelines.

- Provide value arguments for the use of AI and documentation on the current use of AI for content creation.

- Work with communities and stakeholders to ensure data is complete and unbiased.

- Identify skill gaps between teams and team members that could be areas for investment, and advocate for those upskilling resources.

Share Your Insights on AI in Museums

As AI becomes more integrated into museum work, we want to understand how professionals are using it and what ethical considerations matter most.

Take the authors’ short survey to help shape the conversation on AI adoption, professional development, and museum practices.

Audrey S. Chang, PhD, is Director of Global Affairs at the National Museum of Natural Science in Taiwan.

Brad MacDonald, MS, is an Adjunct Professor of Design and Technology at Parsons School of Design in New York.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Amy Borchard, MA, Karishma Gangwani, PhD, and Sophia Ma, MA, for their enthusiasm, creativity, and energy in supporting the conference workshops.

[1] Notable examples include 2023’s Collaborative Poetry: Co-Creating Verses with AI at the MIT Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Ameca, the robot who curated The Future Is Today exhibition at the Copernicus Science Centre in Warsaw, Poland.

[2] Act as if you are a curator: an AI-generated exhibition, September 9, 2023–February 18, 2024, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, accessed January 30, 2025, https://nasher.duke.edu/exhibitions/act-as-if-you-are-a-curator-an-ai-generated-exhibition/.

[3] DALL-E and Midjourney are AI-powered image generation tools that create images from user-written text prompts.

[4] Everett M. Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations (The Free Press, 1962).

[5] Ronald Ssebalamu, “Innovation Adoption Life Cycle or Roger’s Curve, Medium, February 21, 2024, https://medium.com/@ronaldssebalamu/innovation-adoption-life-cycle-or-rogers-curve-97af9ac36da0.

[6] A large language model (LLM) is an advanced artificial intelligence system trained on massive amounts of text data to understand and generate human-like text.

[7] An AI hallucination occurs when an artificial intelligence model generates false, misleading, or nonsensical information that appears plausible but is factually incorrect or entirely made up. This happens because AI models do not “think” or “know” in the way humans do—they predict the most likely words or patterns based on training data, rather than retrieving facts from a verified database.

[8] The Stargate initiative, led by OpenAI, SoftBank, Oracle, and MGX, is a $500-billion AI infrastructure project chaired by SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son. With $100 billion allocated initially, it aims to advance AI capabilities in the U.S. over the next four years. DeepSeek is a Chinese AI startup that has garnered significant attention for developing an open-source AI model capable of effective reasoning while utilizing substantially fewer resources than traditional models.

[9] James Holdsworth, “What is AI bias?” IBM, 2023, accessed January 30, 2025, https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/ai-bias.

[10] While workflows exist to create and incorporate institution-specific data repositories, these tools and processes are not in common usage and typically require specialized training.

[11] A single workshop participant responded to the prompt used to generate the data for figure 5, but did not answer the prompt used to generate the data for figure 4.

[12] Such as the thoughtful toolkit shared by The Museums + AI Network. https://themuseumsai.network/toolkit/.

[13] “New funding to scale the benefits of AI,” OpenAI, October 2, 2024, https://openai.com/index/scale-the-benefits-of-ai/.

[14] Nischal Tamang, “Machine Learning Stirs Controversy in Nobel Prize in Physics,” Harvard Technology Review, November 18, 2024, https://harvardtechnologyreview.com/2024/11/18/machine-learning-stirs-controversy-in-nobel-prize-in-physics/.

[15] AI performs specific tasks, while AGI would think, learn, and adapt like humans. AI exists today, but AGI remains theoretical.