At a time when much of the nation is thinking about what citizenship means, museums, historic sites, and other cultural organizations are uniquely poised to offer the public opportunities for civic engagement through direct encounters with authentic and original collections. The public perceives our institutions as highly trusted sources of information and learning; as such, our collections are ideal resources for fostering greater civic knowledge and understanding. As museum practitioners, we have a responsibility to promote a civil society by offering stimulating educational initiatives and making our museum resources and spaces accessible as part of the civic process.

Given its mission to promote the awareness and understanding of history, science, and service, the Intrepid Museum embraced the chance to make civic engagement more tangible and relevant to elementary students in New York City. During the school year 2023-2024, the Museum received one of five K‑5 Implementation Grants from Educating for American Democracy to create a pilot program that used Museum content and collections to encourage civic teaching and learning through museum-school partnerships. Based on an inquiry-based framework called the Educating for American Democracy (EAD) Roadmap, the resulting toolkit, Exploring Civics through Historic Spaces: A Model for Civic Learning at Museums, Historic Sites, and Cultural Institutions, is itself a roadmap for cultural organizations looking to find civic connections through their collections.

Why Civics?

With the 250th anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence quickly approaching, conversations about what it means to be a citizen, remain civically engaged, and live in a pluralistic society are becoming more amplified and applicable than ever. Despite the country’s intense political polarization, a 2020 Brookings Institute study indicated that Americans have a “lack of engagement in civic behaviors [as well as] reduced participation in community organizations and lackluster participation in elections, especially … young voters.” Currently, forty-two states require at least one course in civics. Yet, few Americans can name the three branches of government or understand how these branches work together and shape local communities. Museums have an opportunity to take up the challenge of fostering both civil and civic dialogue, using their collections as a jumping-off point. Artwork, objects, oral histories, archival materials and historic sites themselves reflect the diversity of the country and our shared histories. In his book The Civic Mission of Museums, Anthony Pennay writes:

“Civic learning is about far more than the acquisition of knowledge. Effective citizens, those who value contributing to a better community, don’t just gather and store knowledge. They also have to learn how to apply the knowledge of the past to the present.”

By supporting and implementing civic learning, contributing to civic understanding, and increasing the public’s civic mindset, museums can help cultivate an engaged citizenry and serve as effective places for civic learning and dialogue.

Educating for American Democracy

The EAD Roadmap is an inquiry-based framework designed to enhance history and civics education for all learners. The framework organizes history and civics content into seven themes and five design challenges, reflecting a logical progression without a strict hierarchy (see below). It spans four grade bands (K–2, 3–5, 6–8, and 9–12) and reflects core pedagogical principles, highlighting the dilemmas educators may face. Each theme includes questions and key concepts for K–12 history and civics and sample guiding questions for educators. The themes start with the goal of preparing citizens for self-government, progressing from the formation of communities and government to the development of the US constitutional system. They then explore American political development, global context, and conclude with the importance of civil disagreement and civic friendship in upholding shared political principles.

| Civic Themes | Design Challenges |

| Civic Participation | Motivating Agency, Sustaining the Republic |

| Our Changing Landscape | America’s Plural Yet Shared Story |

| We the People | |

| A New Government and Institution | Simultaneously Celebrating and Critiquing Enterprise |

| Institutional and Societal Transformation | Civic Honesty, Reflective Patriotism |

| A People in the World | Balancing the Concrete and the Abstract |

| Contemporary Debates and Possibilities |

Source: Educating for American Democracy Roadmap

Proof of Concept

To meet our goal of establishing a model for collaboration between an individual school and a local historic site or museum, we developed the Exploring Civics toolkit for museum educators. As our partner for the pilot, which would lead to the toolkit, we collaborated with P.S. 51, The Elias Howe School, an urban, Title 1 public elementary school serving a diverse student body of four hundred students located in New York City’s Hell’s Kitchen neighborhood. We worked with students and teachers in grades 1 through 5.

Museum staff identified content areas and programming at the Intrepid Museum that already engaged with civics. These included discussions of underrepresented groups who served aboard the historic ship, USS Intrepid, and policy changes in Naval history since World War II. We also relied on the New York State P-12 Social Studies standards and P.S. 51’s use of the Learning for Justice Social Justice Standards to inform the work. Discussions of community are particularly relevant to this school, which is located at the edge of a rapidly gentrifying area while also experiencing a high influx of immigrant students. Our Museum educators faced the challenge of making the program accessible to a number of students with no grounding in US history and limited ability to speak English.

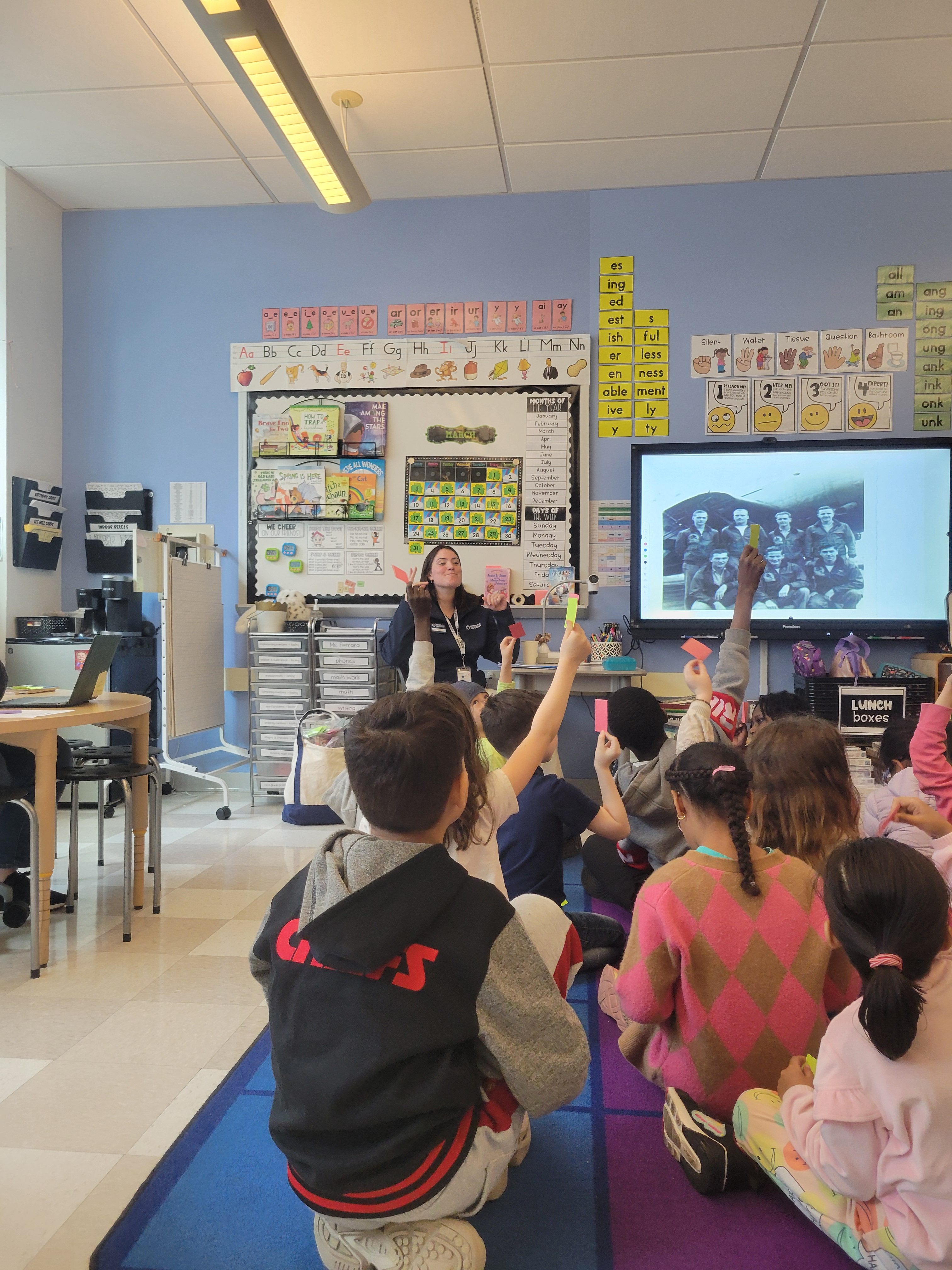

As a result, the lessons we developed focused on defining a community, investigating policies and practices that impact the makeup of a community, and exploring how those policies and practices can change over time. At the Intrepid Museum, students explored primary sources that centered on the lives of crewmembers who lived and worked on board the aircraft carrier Intrepid during World War II, the Cold War, and the Vietnam War. They also focused on the policies and practices that limited who could serve and in what capacity.

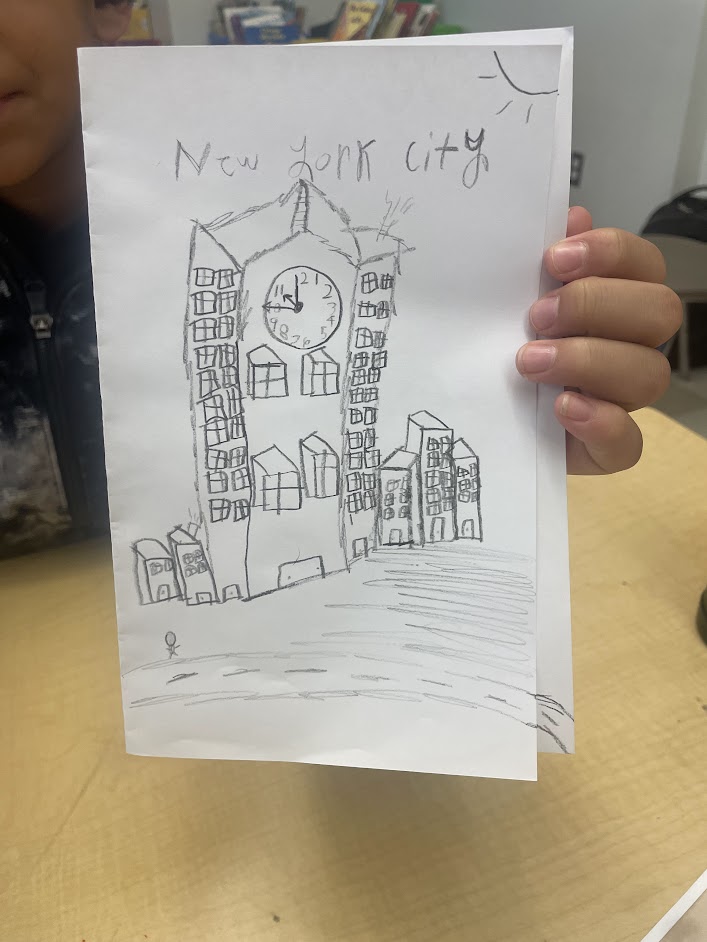

Content was adjusted to be age-appropriate and speak to themes already being taught in each grade. To tie in with the world cultures study in the NYC Scope and Sequence for Social Studies, for example, third-grade students discussed the range of cultural backgrounds of the crew on board the USS Intrepid, the many places around the world that its crew visited, and which values were important to the Navy as an institution. They compared these ideas to the cultural diversity in their school, the agreements in their classroom, and how they welcomed newcomers to their communities. After they looked at the “Port of Call” booklets that Intrepid crewmembers received when visiting a new place, students created welcome guides for new students at their school. In the final session, we invited students and their families to the museum for a cultural celebration, where they could bring food and clothing important to their communities.

Lessons Learned

Educators at the Intrepid Museum faced a series of challenges as they brought these activities to life. In addition to the aforementioned lack of familiarity with United States history, many of the students at P.S. 51 spoke only Spanish, and some did not read yet in any language. To overcome this, we made sure that at least two Museum educators visited the school before each session, including one bilingual educator who worked directly with the Spanish-speaking students, translating and facilitating their participation in each group discussion.

Using the primary sources in the Museum’s collection was also a challenge for the students. The “Port of Call” booklets, for example, were written exclusively for English-speaking adults. To make the booklets more accessible, educators created illustrated versions with pictures of foods, places, and objects and eliminated the text. These pictorial versions also appealed to students with learning disabilities.

Another challenge educators faced was confusion over the roles of teachers, administrators, and families. Although Intrepid Museum educators provided a syllabus to all grade team leads, they were not sure if all the individual teachers in each grade knew what would take place in each lesson. Teachers said they wished they had known sooner how the content connected to their classroom work. Meeting with entire grade teams regularly would have helped teachers understand the content of each lesson and make connections in their classrooms.

A final challenge came with the culminating cultural potluck at the Museum. Although we gave each class fliers in both English and Spanish and encouraged students to come, the turnout was very low. We concluded that many families did not understand what the event was or how it connected to the rest of the program. When planning a weekend program, we realized, it is important to regularly remind families about the event and plan far in advance. It is also important to ensure that teachers understand how the content of the weekend program connects to the classroom work and, if possible, pay school staff to attend.

Expanding Civics Learning

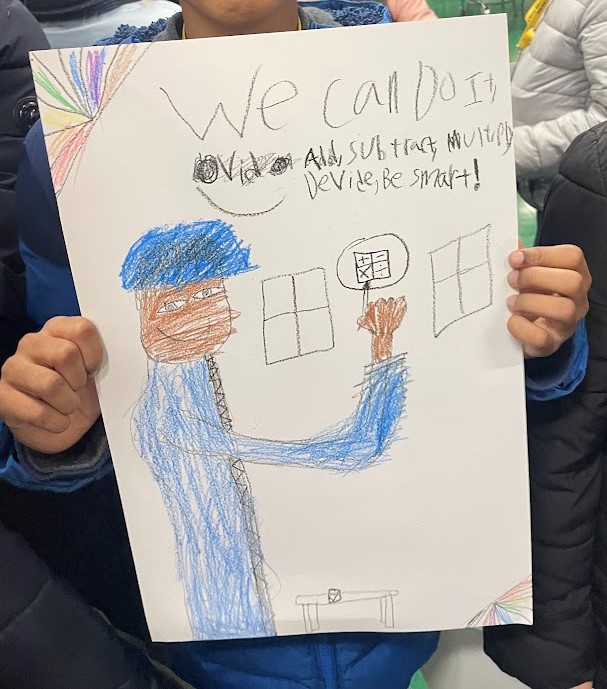

After conducting an evaluation and peer review of the pilot program, we believed the Exploring Civics toolkit was ready for broader use. Consisting of 14 lessons spanning grades one to five, the toolkit is ideal for museums, historic sites, and all cultural institutions looking for ways to mine their collections and exhibits and create civics-aligned school-museum partnerships. The lessons in the Exploring Civics toolkitare designed to allow institutions to adapt the toolkit structure to their own collection resources. Each of the 14 lessons provides objectives and lays out clear key concepts as well as methods for assessment with the goal of fostering civic mindsets, skillsets, and actions at grade developmentally appropriate levels. The wide-ranging civics themes offer opportunities for creative collections connections as well as relevance to students’ lives. The toolkit also provides tips on fostering museum-school partnerships, advice on how to choose collection materials, and concrete lessons learned from the pilot program.

The Exploring Civics toolkit includes age- and developmentally appropriate approaches to the discussion of community, what it means to belong, and what it means to work for change as an individual and as a group for each grade, using historic collections to illustrate these concepts. It is not a one-size-fits-all program but is instead designed to be modular, flexible, and adaptable based on the needs of individual organizations. For example, if your museum consistently works with the entire third grade in a district, great! Take a look at the third-grade lessons, where students are encouraged to explore the cultural diversity, traditions, and values in their communities and compare them with the traditions, cultures, and values of the community or communities interpreted at your historic site or museum.

Getting Started

Available from the Intrepid Museum Learning Library, the Exploring Civics toolkit is easy to put into practice:

- Fill out the Primary Source Focus Collections Survey to see which exhibitions and items in your collections connect to each lesson.

- Partner with a school or schools in your area.

- Share the program outline with the school and set up a time to discuss potential dates over the course of a year. Review the “School Communication Recommendations” in the toolkit to determine how best to meet the school’s needs. Remember that lessons can be added or skipped at any point in the process. (TIP: Build in ample time for this planning stage, especially if the school is a new partner for your institution.)

- Review your local and state civics and history standards to see how they align with the toolkit’s Education for American Democracy–based lessons

- Review lessons to determine the materials and set-up you’ll need for each lesson.

- Create a schedule for lessons to be taught to the students.

- Refer to the toolkit for further recommendations.

Very interesting and important endeavor for museums. It would be helpful to have specific examples on how to use traditional art works to integrate civic content. It occurs to me that one can take any art object and explore how it is similar to our community, how it differs.

Examples integrating some civics concepts would be helpful.