This article first appeared in the journal Exhibition (Fall 2025) Vol. 44 No. 2 and is reproduced with permission.

Is it possible to fully understand someone’s point of view? What tensions might arise from wanting to understand, but not physically inhabiting the lived experience of another?

In Feeling: Empathy and Tension Through Disability explores these questions. On view from August 30, 2025, through January 4, 2026, at the Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia (UVA), the exhibition features works by nine contemporary artists that reckon with how we empathize. Stemming from the Greek terms em—“in”—and pathos—“feeling”—empathy implies the action of understanding or experiencing the feelings and thoughts of another. Yet the practice of empathizing—being aware of and sensitive to the experience of someone else—can also engender tensions around stigmatization, idolization, fetishization, pity, and fear.

Exploring the relationship between empathy and tension through lived experiences of disability, In Feeling highlights and celebrates perspectives that challenge assumptions about ways of being and living. The works in the exhibition engage with themes surrounding communication, connection, and rest, asking visitors to reimagine how they connect with and understand others. In Feeling values disability not as an object of pity or inspiration but as creative freedom, liberation, and care. Participating artists include JJJJJerome Ellis, Jerron Herman, Molly Joyce, Jeff Kasper, Christine Sun Kim, Park McArthur, Finnegan Shannon, Andy Slater, and Liza Sylvestre.

This article is co-authored by the exhibition’s curators and details our experience of planning In Feeling. It was written between February and June 2025, when the exhibition was still in development. Throughout the text, we have endeavored to indicate what elements have been completed, are in process, and those we hope to implement before opening. We provide key findings on both working with disabled artists and organically embedding accessibility in the museum space. In so doing, we seek to offer approaches and proactive takeaways for museum professionals hoping to work, collaborate, and partner with disabled artists and to develop accessibility standards for exhibitions of all kinds.

Through its conception and planning, In Feeling attempts to counter ableism and practices of exclusion. Museums often perpetuate ableist practices through exhibition design, lack of representation, and an absence of accessibility standards in policy and programming. As a result, they often privilege “an impossible bodily standard,” leading to hostile spaces that are othering to disabled bodies and that discourage or prevent participation by disabled visitors.[i]

In Feeling offers a new format and focus for the co-curators, museum, and UVA. While recent exhibitions have addressed empathy or featured the work of disabled artists—All Together, Amongst Many: Reflections on Empathy at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts in Omaha, Nebraska, and Crip* | Artists Engage with Disability at the Weatherspoon Art Museum in Greensboro, North Carolina, for example—In Feeling—explores the intersections between lived experiences of disability and understandings of empathy. Moreover, this exhibition is the first at the Fralin to engage with disabled artists and disability as its focus.

Approach

The idea for the exhibition began with a Charlottesville iteration of co-curator and author Molly Joyce’s ongoing work Perspective. The project, which commenced in 2020, was born from frustrations Joyce experienced while navigating her disability (an impaired left hand from a car accident) and common themes of disability culture. Joyce pitched the work to former Fralin Associate Curator Hannah Cattarin in fall 2022. They began discussing the concept of “perspective” and how it applied to the disabled experience, an experience that is recognized but not necessarily longed for. This discussion expanded to working with co-curator and author Kristen Nassif, who joined the Fralin in July 2024. Together, we (Joyce and Nassif) developed an exhibition that underscores the potential for simultaneous understanding and tension when empathizing with disability perspectives.

Our intention was not to curate a “disabled artist exhibition” or an exhibition only about disability. Instead, the themes and artworks of In Feeling organically emerged from conversations with artists. Inspired by Joyce’s experience as a practicing artist, we decided to pursue an artist-led curatorial approach, driven by conversations with the artists to identify works that they felt best represented their practice and fit the exhibition’s focus. “Working with Molly and Kristen has been a fruitful example of [how] when institutions employ artists, particularly disabled artists, they build trust with a community,” Jerron Herman writes. “We can expect the ethics or principles of the artist, who is already rooted and rigorous in their attention to access, to inform the future of that institution’s exhibitions and programs.”[ii]

Exhibition Themes & Select Artworks

Many works in the exhibition introduce accessibility measures and visitor practices that are uncommon in traditional exhibition settings. Andy Slater’s Invisible Ink series (2018–ongoing) consists of non-visible paintings that can only be experienced through alt text, shifting the locus of the artwork from visual object to descriptive language. As Slater explains, “The audio is actually the accessibility and the text is the piece. But the text is the access. But the access is the piece.”[iii] By foregrounding an accessibility component as the medium, Invisible Ink posits whether access is and can be an art form in and of itself.

Similarly, Jeff Kasper’s and Park McArthur’s works reframe how audiences physically interact with art. Kasper’s wrestling embrace (2017–ongoing) takes the form of a wrestling mat and playing cards, inviting visitors to find a partner with whom to practice conflict and care exercises in interpersonal relationships. McArthur’s Polyurethane Foam (2024) is a sculpture made from high-density foam that is useful in absorbing both sound and the impact of a body on objects like wheelchairs. Its striking scale invites visitors to focus on the material and consider how time and gravity have reshaped its form, with visitors invited to touch and interact with it.

Finnegan Shannon and JJJJJerome Ellis further disrupt conventional “do not touch” mandates by inviting rest. The Fralin’s iteration of Shannon’s seating series, Do you want us here or not** (2018–ongoing), will feature the phrase “*Heavy sigh* . . . sit if you agree.” Asking visitors to engage physically and emotionally, this bench blurs boundaries between artwork, artist, and audience. Ellis’s newest commission Sonic Bathhouse #2 (2025) offers an immersive alternative to typical museum viewing. Rather than orienting visitors within the space, the work invites them to simply occupy it, encouraging flexible, unstructured modes of engagement that reject fixed routes and predetermined interpretations.

From the chosen works, we developed three themes: communication, connection, and rest. These themes are inherently interrelated concepts and experiences that encourage audiences to reconsider how practices of empathy shape and are (re)shaped by different lived experiences. For instance, some works question whether verbal or visual communication takes precedence, while others confront traditional notions of rest in museums, prompting reflection on where and how it is fostered. Together, they challenge and expand what art can be, who it is for, and why it matters.

Accessibility: Motivating Change at the Fralin

Creating an accessible space—one that would foster empathetic experiences and in which all visitors could participate—was paramount. To center multimodal approaches to art and accessibility in the exhibition, we needed to consider how museums have traditionally reinforced behaviors and rules that uplift abled bodies over disabled ones. At the same time, we needed to think carefully about how In Feeling’s design could call attention to and counter certain assumptions and expectations of our visitors. These include, for instance, preferences for ocularcentric art (which privileges sight and the visual), passive viewing practices, curatorial authority, and swift pacing. We realized early on that these considerations could have long-lasting impacts on future exhibitions at the Fralin, improving overall visitor experience and staff working culture.

Consultants and Training

We partnered with the Institute for Human Centered Design (IHCD) and user experts Lindsay Jones and Andy Slater to ensure that the exhibition’s design was thoughtful and inclusive. Founded in 1978, IHCD has worked with various institutions, including art museums, to create designs that expand and enhance experiences for people of all abilities, ages, and cultures. We were particularly drawn to IHCD’s commitment to design as a “social art,” which complemented our imperative to underscore access as aesthetic and not solely as compliance and accommodation. IHCD, Slater, and Jones consulted throughout the exhibition design process, advising on layout, gallery seating, descriptions, printed materials, and technology considerations for audiovisual works (fig. 1).

While our focus as co-curators was on the exhibition, we also recognized that significant time and energy were needed to address access barriers across the museum. The Bayly building, which houses the Fralin, opened in 1935.[iv] Like much of UVA’s campus, it features a Jeffersonian, Neoclassical architectural style. The building presents many accessibility challenges, not least that the museum’s main entrance is only accessible via stairs. Parking and bus access are also ongoing problems.[v]

In Feeling offered an opportunity for sustained assessment and investment by the Fralin to produce tangible, long-term accessibility improvements. IHCD conducted a two-day site visit in January 2025 to assess the physical structure of the building and to meet with various museum departments. Their reports, received at the beginning of March, offered a host of recommendations and solutions to both meet ADA standards and further increase access through inclusive design. The facility report detailed improvements such as updating museum signage, installing restroom grab bars and stair handrails, and suggestions for better visitor circulation. The exhibitions report addressed artwork didactics, visitor prompts, navigation, and access for blind or low-vision visitors (BLV). We aimed to address some of these items within In Feeling, and the Fralin continues to work through other items, which vary in cost and scope, with continued support from IHCD.

From these suggestions, we planned a series of staff trainings with IHCD to workshop new accessibility measures and create a welcoming space for all visitors. The first session, held in June 2025, focused on visitor experience and served as an introduction to common museum barriers for BLV visitors (fig. 2). An exercise with Fralin-specific scenarios asked staff to reflect on current strengths and weaknesses with regard to inclusion and access. Two additional training sessions will focus on visual and audio description. We will also conduct multiple museum education and docent training sessions after exhibition installation to familiarize educators with In Feeling’s artworks and accessibility measures. Motivated by our work with IHCD, Nassif created the Fralin’s Accessibility Team, which will work to develop accessibility standards for the museum’s exhibitions, programs, and website as well as build upon connections with local organizations and communities.

Artist Engagement

At the same time, we wanted to bring the exhibition’s artists into these conversations about accessibility. We met with each artist at the outset of exhibition planning to determine specific access needs. As the exhibition developed, we invited artists to weekly project management meetings as needed, connecting artists directly with our exhibition designer, technology partners, and staff in the museum’s Education Department. In addition, we asked exhibiting artists to create descriptions of each other’s works. Featured in the gallery alongside curatorial labels, these descriptions offer unique perspectives that we hope will deepen connections between artworks. We developed individualized artist contracts following W.A.G.E. guidelines to ensure equity and fair compensation for all these efforts.

“The comfort and absolute satisfaction of working with curators who refuse to treat accessibility as an afterthought is immeasurable—and that’s exactly how I feel about this exhibition,” Andy Slater writes. He continues:

I didn’t have to sit through endless meetings about accessibility or explain my own access needs. I didn’t have to stress. And if you only knew how important that is to me. . . . Too often, I’ve had to take on extra labor just to make a show accessible because curators didn’t understand what my work required. Too often, I’ve had to write all the descriptions for my own pieces just to ensure they’d get done. But not this time. Instead, I was commissioned to describe another artist’s work—a brilliant idea. To me, accessibility is best when it’s creative and collaborative, and inviting artists to create access for one another is an act of care and love.

We are all having our rights and access stripped from us more and more each day. Who can we trust?

The folks in this show. That’s who.[vi]

Commissioning site-specific works by Joyce, Ellis, and Shannon enabled us to further address specific access parameters at the museum. In addition to Shannon’s bench, we commissioned the artist to produce a site-specific wallpaper in the museum’s accessible entrance (fig. 3). Inspired by their Anti-Stairs Club Lounge, the wallpaper features a collage that includes archival photographs and architectural plans of UVA’s Bayly building (which houses the Fralin), images from the 1990 Capitol Crawl,[vii] and quotes from disability activists. Shannon’s work directs attention to both the built environment and the historical context of disability rights, reinforcing access as both a spatial and a political concern.

Layout & Design

We aimed to embed accessibility in all aspects of In Feeling: in its planning, design, and visitor experience. Accessibility is typically something museums “do” for visitors—create spaces and exhibitions that are welcoming to all. We, however, wanted to educate and involve visitors in the work of accessibility as a way to connect with the exhibition’s artists and themes.[viii]

The exhibition’s layout will help set the tone. Kasper’s work sits in the center of the main exhibition space, a large gallery on the second floor of the Fralin. Slater’s paintings appear on the gallery’s back wall next to the introductory text (fig. 4). This not only creates a striking sightline when visitors enter the gallery and face a large, seemingly “empty” wall, but also makes a statement about the kinds of art the exhibition aims to celebrate. Indeed, we consciously decided to minimize the number of temporary walls in the exhibition, creating one large, continuous space where artworks and visitors could better interact.

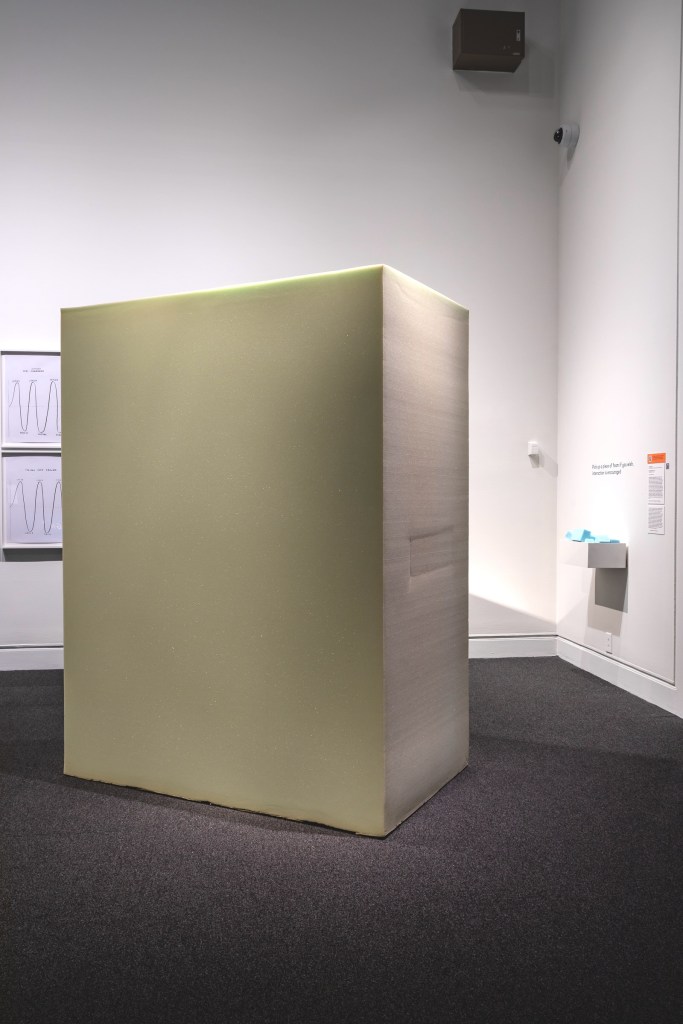

We also aimed to create intentional space around, between, and within each artwork. For example, Ellis’s Sonic Bathhouse #2 is the sole occupant of a large adjoining gallery off the main exhibition space (intro image). While curatorial instinct is typically to fill spaces with things, we instead chose to embody the exhibition’s themes of communication, connection, and rest by designing physical spaces that encouraged empathetic experiences.

To familiarize visitors with the exhibition’s accessibility measures, a panel close to the entrance lists information about In Feeling’s technologies, didactics, artworks, and design—all of which are new to the Fralin. For instance, labels in the exhibition contain NaviLens Accessible QR codes, which are detectable from long distances and at various angles. These codes link to a screen-reader accessible webpage containing audio and written descriptions.

We also alert visitors to prompts for multisensory engagement throughout the exhibition, which for audio and audiovisual works include vibrotactile pillows and benches.[ix] Additional prompts appear throughout the gallery to sit, rest, and touch. For example, next to McArthur’s sculpture (which itself is touchable) is a shelf with similar, smaller pieces of foam. The wall text invites visitors to pick up and handle these objects, emphasizing tactile engagement and intimate experiences with the artwork (fig. 5). Additional offerings in the gallery space include large print and braille booklets, which contain the exhibition’s labels and descriptions.

Finally, the collaborative nature of the exhibition, detailed above, felt especially important to stress to our visitors. Access, as artist Carolyn Lazard and writer Mia Mingus have explained, is an ongoing, speculative practice, one that evolves with a community and is inherently relational and human.[x] In this spirit, we encourage visitors to join us and the exhibition’s artists by creating descriptions of artworks of their choosing. Visitors can submit descriptions via a NaviLens code, which we plan to publish on the Fralin’s website. Exhibition programming, which will include performances by Ellis and Herman, a workshop with Kasper, and an artist panel discussion, seeks to further connect visitors with artists. We aim to offer programs of different formats and lengths, ranging from in-person activations of the exhibition space to virtual, interactive workshops and discussions.[xi]

Together, the exhibition and its programs celebrate access as a creative endeavor that can uncover unexpected connections and new forms of understanding between visitors and artists.

Challenges & Takeaways

In so many ways, In Feeling is an experiment: it introduces new approaches, collaborations, interpretations, and experiences to the Fralin. While many aspects of the exhibition are productive in nature, there were many challenges we faced along the way.

The Fralin is a small museum. With a staff of only 25, the museum does not have a dedicated accessibility advocate or manager. All the accessibility work fell on us as co-curators, with the support of other staff when possible. Moreover, the museum recently underwent a significant personnel turnover, with over a third of its staff starting in the past two years—including Nassif.

As a result, most of the planning for In Feeling occurred over a short period of 12 months. The timeline required that we make decisions swiftly and prevented us from developing an advisory group to evaluate our ideas and initiatives. Implementing IHCD’s suggested improvements also proved difficult within this condensed time frame, especially at UVA, a UNESCO Heritage Site and National Historic Landmark where any sort of proposed renovation is complex.

From an accessibility standpoint, some of the artworks presented competing access needs. For instance, we needed to determine how Slater’s Invisible Ink paintings—which visitors must listen to on headphones in the gallery—could be experienced together by tour groups. Likewise, we needed to carefully consider how to invite appropriate touching for McArthur’s foam sculpture and Kasper’s interactive exercises. We worked with our educators to brainstorm solutions for these challenges that would be effective and sustainable for our staff. We will also conduct focused training sessions with museum docents and security to ensure that staff understand the exhibition’s technologies and artworks.

Finally, it is important to mention that at the time this essay was published, In Feeling had only just opened at the Fralin. Evaluating many aspects of the exhibition will be critical in determining if we met our intended goals. We anticipate encountering new challenges over the course of its run, and plan to work closely with museum staff to hear from our visitors and adjust as needed. As we continue to learn from this process, we recognize that accessible exhibitions can and must mean different things to different institutions and individuals. Below is a list of recommendations and lessons learned from our experience thus far:

- Embrace multiple voices early.

Any exhibition that features disability (historical or contemporary) needs to prioritize the lived experiences and perspectives of disabled people from the outset. Co-curate, work with living artists, and engage user experts. Solicit feedback and meaningfully incorporate it into the exhibition’s approach and design.

- Accessibility is best served layered.

There is no one-size-fits-all for an exhibition to “be accessible.” One of the most important lessons we learned from IHCD was to layer accessibility measures as much as possible and offer information in multiple formats. For example, to access the audio works in our exhibition, we provided in-gallery headphones, QR codes on labels, a webpage link, and verbal and written descriptions of the audio online and in gallery handouts. While budgets will oftentimes limit the number of layers one can provide, it is essential to start somewhere.

- Be comfortable with being uncomfortable.

Creating exhibitions about disability and/or improving museum accessibility requires introspection, an openness to change, and experimentation. Working with disabled artists and partner organizations can lead to workflows and practices that undermine traditional curatorial approaches—for instance, increasing the lead time for didactics; fewer works on the checklist; heightened collaborations between curators and IT professionals; and frequent dialogue with artists. Embrace the questions, challenges, and possibilities that result from these changes.

- Collaborate, collaborate, collaborate.

In Feeling is built upon collaborations—between curators, museum staff, artists, technologies, accessibility partners, and local stakeholders. At every opportunity, we have endeavored to build upon and create new partnerships across UVA and the broader Charlottesville community, including the Center for Health Humanities & Ethics, Accessibility Partners Group, Student Disability Access Center, and Kindness Cafe + Play, some of whom have never partnered with the Fralin before.

- Think outside the box.

In planning the exhibition, we wanted to challenge what and where art could be. Many of the exhibition’s elements came about through casual conversations and phrases like “wouldn’t it be cool if . . .” We were surprised by the enthusiasm and support we received from artists, museum staff, and contractors throughout the planning process. Beyond innovation and creativity, pushing boundaries requires collaborative buy-in—find it and cultivate it.

- Write it down.

During the planning process, we corresponded with museum curators, including colleagues at the Weatherspoon Art Museum and the University Galleries of Illinois State, to meet, share information, and ask questions. We also took opportunities like this one to write about our exhibition and its process. It is by talking to one another and documenting our experiences that a repository of ideas and resources grows, leading to more accessible exhibitions in the future.

Access as Connection

In Feeling is an exhibition featuring artists who challenge normative ideals of communication, connection, and rest—doing so through the lens of empathy. But the exhibition is more than that. It has sparked a rethinking of institutional relationships among artists, staff, visitors, and stakeholders. By prioritizing empathy as both an institutional and curatorial value, the museum has committed to ongoing staff training, meaningful acquisitions such as Shannon’s Do you want us here or not, and continued partnerships with local organizations such as the Arc of the Piedmont.{[xii]}

Empathy compels us to reconsider how we relate to museum visitors—who feels welcome in an exhibition setting, and for whom the space is truly accessible. It invites us to ask:

What changes when we are no longer guided by assumptions of difference or expectation?

What possibilities emerge when we simply allow ourselves to feel?

Molly Joyce is Dean’s Doctoral Fellow, Department of Music, at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virginia. ufu2dv@virginia.edu

Kristen Nassif, PhD, is Curator of Collections at the Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia. knassif@virginia.edu

[i] Panteha Abareshi, “Ableist Space // [Disabled Body],” VoCA Journal, December 11, 2020, https://journal.voca.network/ableist-space-disabled-body/; and Shara Mills, “The Architectural Intersection of Museums and Disability Policy,” Journal of Cultural Research in Art Education 41 (2024): 68–81. For more on museums and disability, see Richard Sandell, ed., Re-Presenting Disability: Activism and Agency in the Museum (Routledge, 2010); and Alice Wong, ed., Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century (Vintage Books, 2020).

[ii] Jerron Herman, email message to authors, February 17, 2025.

[iii] Andy Slater, text message to Molly Joyce, March 24, 2025.

[iv] For more on the history of the Fralin, see “History,” The Fralin Museum of Art at the University of Virginia, accessed January 4, 2025, https://uvafralinartmuseum.virginia.edu/about/history.

[v] It is also important to acknowledge the accessibility work museum staff had undertaken prior to In Feeling. This includes the creation of sensory bags, an accessibility page on the website, access to interpretive services, and accessible parking. Our work with IHCD, however, is the first sustained engagement the museum has undertaken.

[vi] Andy Slater, email message to authors, March 6, 2025.

[vii] The Capitol Crawl was part of a larger protest by activists in the disability community to push back against the Senate’s attempts to stall the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act. During the protest, participants abandoned their wheelchairs and mobility aids and began to climb the steps of the Capitol. See, Gianna Barnhart, “When Disability Activists Influenced History: The Capitol Crawl,” Accessible Web, July 25, 2022, https://accessibleweb.com/history/when-disability-activists-influenced-history-the-capitol-crawl/.

[viii] As others have argued, access and accessible museums benefit everyone. Moreover, access and empathy are codependent concepts and experiences. “Making museums accessible,” Maria Chiara Ciaccheri writes, “is about encouraging exchange between different people.” Museum Accessibility by Design: A Systemic Approach to Organizational Change (Rowman & Littlefield, 2022), xix. See also Beth Redmond-Jones, ed., Welcoming Visitors with Unapparent Disabilities (Rowman & Littlefield, 2024); Sameera Kapila, Inclusive Design Communities (A Book Apart, 2022); and Kat Holmes, Mismatch: How Inclusion Shapes Design (MIT Press, 2020).

[ix] We partnered with VibraFusionLab, a media arts center based in London, Ontario, to introduce these technologies into the exhibition space. Vibrotactile technology converts audio sounds into vibrations, thereby creating more inclusive experiences for disabled and nondisabled visitors.

[x] Carolyn Lazard, Accessibility in the Arts: A Promise and a Practice (published online, 2019), https://promiseandpractice.art; Mia Mingus, “Access Intimacy, Interdependence and Disability Justice,” Leaving Evidence, April 12, 2017, https://leavingevidence.wordpress.com/2017/04/12/access-intimacy-interdependence-and-disability-justice/.

[xi] All programs will feature ASL interpretation, and CART captioning will be available during virtual programs. Beyond these artist-focused programs, the Fralin’s Education Department is developing a sort of passport to encourage visitors to connect with local Charlottesville organizations and businesses to increase disability awareness.

[xii] The Art SpArcs program is a partnership between The Fralin Museum of Art and The Arc Studio at The Arc of the Piedmont, a nonprofit supporting adults with developmental disabilities in Central Virginia. Begun in 2023, Art SpArcs offers an inclusive, accessible, and inspiring space for artists with developmental disabilities to engage with art and one another through meaningful artmaking experiences. The program aims to expose participants to new artists, art forms, and art spaces; help participants develop deeper understandings about the creative process; prompt social connections among participants; and provide opportunities to engage with the Fralin and UVA community through art viewing, art creation, and art exhibitions.