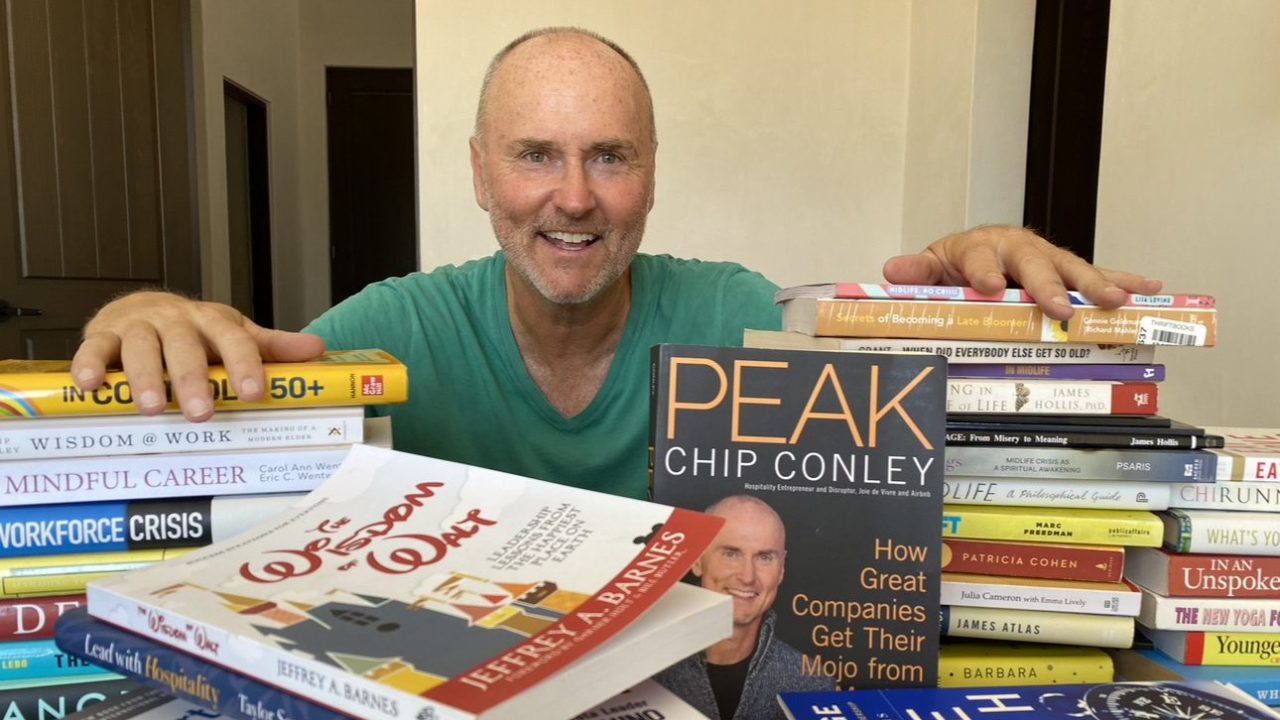

If you’ve ever seen my library or chatted with me about what I’m reading, you’ll know that I have a soft spot for TED Talk–style books. If Adam Grant or Simon Sinek has a new book, I’ve likely already bought it, read it, or I’m waiting for my library’s copy. I didn’t always love these types of books, but after being introduced to the works of Chip Conley, and reading and re-reading everything he’s written, I became an easy convert.

Chip gained “break all the rules” fame and notoriety during his early days as a hotelier in California and later as a culture disruptor brought in to shake up Airbnb. He is now an evangelist helping us rethink the second half of our lives with his Modern Elder Academy (MEA), a retreat center focused on helping people in midlife reach their full potential. In our conversation below, Chip and I talked about this new chapter with MEA and the role that cultural organizations like museums and libraries can play in the lives of our modern elders.

Adam Rozan: You’ve had an extraordinary career journey—from being a hotelier to helping Airbnb recognize the importance of culture to helping people revitalize the second half of their lives. As I learned more about your current work, I was curious about how museums and libraries could engage in the shift in attitude, involvement, and fulfillment that individuals experience during the second half of their lives.

Chip Conley: It’s a question of focus: are there things that you might have seen elsewhere or that you’re aware of in the museum space that you’d like to see brought into that focus? I hope museums, the space, and the positions become secondary and tertiary support systems for those in their midlife.

AR: It’s a question of all the many ways, both internal and external, that a museum can and should support those in their midlife. Is this similar to your first hotel in San Francisco, which attracted touring musicians and became a destination for visitors and a resource, too?

CC: In a way, yes. [Museums] could say, here’s an audience with a need, and we can be helpful. Another way to say this, I think, is if museums saw themselves as guides—guides for reflection and insight—that would help. If I were a museum director today and was trying to think about how to make myself relevant and broaden my museum’s appeal, I might ask how people see a museum as an alternative to how we used to see a church.

AR: Wait, a church? Do you mean the hip kind of church, whose services double as concerts, or the “shhhh, you’re in a cathedral” kind?

CC: What you want is to be a place of activity. You used to go to a church for reflection, insight, and maybe guidance. How can a museum serve that role, especially for someone in their forties, fifties, or sixties? A simple way to do this would be to host members’ events once a month.

How do you adjust your aperture? How does being part of that community allow you to perceive life differently? If you find success there, you can create support groups. The framing, I believe, is asking how a museum in modern society takes the role that the church once held in a traditional society.

AR: So, how would you describe the MEA philosophy on midlife?

CC: Are you familiar with the writings of Erik Erikson, a mid-twentieth-century writer who said that the most important thing in the seventh of eight stages of life that we need to get clear on is “I am what survives me”?

And “I am what survives me” speaks to this idea of generativity—the premise of wanting to generate something in the world constantly and doing it for future generations. What we’ve done in the United States is create a bit of age apartheid, such that there’s a divorce between the young, the old, and those in the middle.

AR: How do we shift from a youth-centric approach to a more balanced appreciation for those in the middle of their lives and our seniors? How can we make midlife and senior life trendy and appealing? Even my language feels outdated…

CC: This didn’t just happen; the work of Madison Avenue and Hollywood had an enormous impact. My vision is more of an intergenerational potluck, where we’re learning from each other across the generations. Because in the past, the old—not the modern elder, the traditional elder—was not necessarily curious. They were wise, and they dispensed wisdom. But a modern elder has as much to learn from a twenty-year-old as the twenty-year-old has to learn from them.

AR: What needs to change in how we socialize with each other, particularly with people of different ages? Can we create opportunities for various generations to sit down and engage with one another?

CC: You should check out generationsoverdinner.com, which could be a great program for museums to explore. It’s an initiative MEA started where we bring multiple generations to a dinner table. You could do this with many dinner tables in a museum, almost a Jeffersonian dinner where there are questions on purpose or relationships or solving societal problems. We’ve done dinners throughout the country. One outcome has been challenging the conversation to move beyond just thinking about retirement and regeneration—literally, how are we constantly regenerating ourselves?

AR: Before we wrap up, let’s talk about you. I’d like to know how you find balance in your life.

CC: I meditate a lot, which does help. But beyond that, I surround myself with really talented people who are as passionate as I am about what we’re doing. I let them do a lot of the work. I delegate. That’s a key thing: how do you create the conditions for people to do their best work? That’s what I try to do.

AR: That makes sense. If I understand correctly, you’re also a cancer survivor.

CC: That’s right. I’m in the midst of it still. As cancer rates continue to soar in this country, and we’re still looking for the causes, you have to work and do these various things and also want to contribute. I have stage three prostate cancer that’s spread beyond the prostate, and the thing I look at is: how do I see cancer as a school? I mean, you know, cancer is my teacher, and what I’m looking for is for cancer actually to give me some insights. So far, I’ve learned:

- I don’t have to be the hero.

- I need to be able to ask for help.

- I need to get really clear on what’s important to me and invest my time accordingly.

- And I need to look at my body as my best friend—something to be taken care of.

Those are some insights I’ve gotten from cancer school. My goal is to graduate with honors from cancer school and be a better person as a result of it.

AR: What you are talking about isn’t necessarily about being healthy; it’s about a life full of wellness.

CC: Yes, that’s right. I called my first company Joie de Vivre for a reason, Adam. It was a daily reminder for me that joy is such a core foundation of living a good life. I’m a bit of an accomplishment junkie, for sure. So, looking for joy in things is an important practice.

AR: I get that. Also, wouldn’t trying to be the best at everything be stressful and even the antithesis of joy?

CC: One of the most important things in midlife is to become a beginner again at something new. In my mid-fifties, I learned how to surf. In my mid-fifties, I started learning Spanish. I’m not very good at either one of them. But one of the questions I ask myself is, ten years from now, what will I regret if I don’t learn it or do it now? And those were two of the things that came up. Even though I have a mindset that says, “I’m too old to do this,” I realized I needed to do it.

AR: So, it’s about mindset?

CC: Mm-hmm. Curiosity and an openness to new experiences are two of the most common variables among people who live a longer, healthier, happier life. If you can start from the practical side, curiosity and openness to new experiences are like taking vitamins—mental and emotional vitamins. Secondly, there’s joy in learning something new and becoming something new. You don’t have to be good at it. But to say, “Oh, wow, I just took a really great photograph there,” and to feel like, “I have capacity in areas I didn’t know I had capacity in.” There’s an emotional elevation that comes from it. It’s about connecting and being in community with one another.

AR: And that’s the point of all this.

CC: That’s right. Coming together, being with one another, and growing into yourself as a modern elder is what it’s all about.