The ethical stewardship of our cherished collections has increasingly become a priority for North American museums grappling with centuries of Eurocentric and colonial-imperial history. Museums are enhancing stewardship of their physical collections by collaborating with stakeholder and descendent communities, reinterpreting exhibits, and reassessing the sources of their funding and donations.

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2025 issue of Museum magazine, a benefit of AAM membership.

» Read Museum.

These changes are visible and celebrated. As a next step, museums are also learning how to tackle internal descriptive and cataloguing practices that have historically lacked linguistic standardization and a moral code. Mass digitization efforts often publish years of legacy data with little or no context. This, combined with the growth of digital collections, affects both internal and external users who wish to access collections and the metadata accompanying them.

We have been confronting this problem at the Harvard University Herbaria. The sources of derogatory language in a natural history record are many. When a natural history specimen is digitized, information is typically transcribed verbatim from labels that often contain historical language and geographic names, some of which are unacceptable by modern social and ethical standards. Database records preserve the perspectives of early collectors, including culturally insensitive descriptions.

Additionally, during record creation, museum cataloguers have historically provided their own narration as curatorial remarks. While a bare bones approach to object cataloguing holds true to the identity of the object (i.e., capturing the information provided by the collector as is), and verbose curatorial notes are useful internally for staff, neither necessarily translates well to a public interface when collections are digitized and published to an online database.

With natural language processing and data science, museums can begin to recontextualize their digital databases and continue to promote equitable access, even with limited or shrinking resources. Addressing these issues retroactively can help us think ahead to creating documentation standards that focus on access and the ethical stewardship of our collections.

Why Worry About Digital Records?

Digitization makes collections more accessible, but uncontextualized records can hinder searchability and perpetuate harm. Additionally, if a digital collection user is unfamiliar with antiquated location names or plants’ common names or descriptions, they are unlikely to obtain the search results they desire.

Imagine, for example, a graduate student who decides to investigate the historical plant biodiversity data of Mount Jefferson in North Carolina. Searching a herbarium database for “Mount Jefferson” yields only a few results. The student might assume there is no critical mass of historical data derived from Mount Jefferson that would be useful for their research and move on to a different locality. What they could not know without more extensive research is that the bulk of herbarium specimens collected on Mount Jefferson were obtained when this mountain was known by a different name: Negro Mountain and its pejorative term.

While it is difficult to track how often external database users stumble across derogatory language accidentally, internal users and digitizers are on the front lines of confronting how to transcribe labels with such terms. Perhaps not surprisingly, most collections undergoing large-scale digitization do not have an established protocol for staff to consult when facing derogatory language.

In many cases, high-speed digitization demands little to no added context by the digitizer—verbatim transcription is the norm. When museums publish label data verbatim to an online database, they inadvertently disseminate the original collecting agent’s voice and personal biases, which may not align with current institutional values. Databases are therefore not neutral spaces and require greater curation than they currently receive.

Existing Solutions to Challenges

An increasing number of museums are using general disclaimers about any offensive content in their collections (for example, see the statement for the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology of Harvard University Collections Online). Those that can devote their limited resources to reparative digitization might use brackets or institutional notes to clarify and contextualize historical language. A digitized herbarium specimen collected in the 1930s at “Negro Mountain” could be contextualized by adding the modern accepted name in brackets: [Mount Jefferson]. A few added words can provide even more context: [Historical name for Mount Jefferson].

However, this example, with a known offensive term and an official one-to-one replacement, is much more straightforward than many cases. Because the implications and uses of derogatory terms can vary so greatly in a single collection, museum employees must consider using their time and resources to do research, discuss their options, and apply the best workflow for each example of derogatory language on a case-by-case basis.

In a 2022 survey that Madeline Schill, an author of this article, conducted as part of her graduate capstone project, respondents representing 16 anthropological and natural history museums across North America and New Zealand cited three main challenges inhibiting the creation of a derogatory language protocol at their institutions: disagreements among staff; the ineffectiveness of a one-size-fits-all solution; and limited internal capacity for resources like staff, time, and funds. They also cited the difficulty of identifying derogatory terms and a general lack of specialized linguistic knowledge among museum staff.

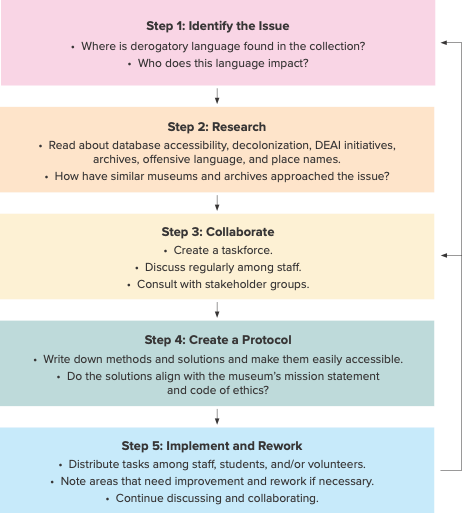

In response to these challenge areas, Schill created a Derogatory Language Treatment Framework (on p. 30) to guide staff through brainstorming solutions for their digitization workflow and drafting a protocol. However, it does not address the challenge of finding the specific records containing derogatory language in the database in the first place.

Leveraging Data Science in Digital Collections

In early 2024, Schill and Kathy Jones, the other author of this article, began using data science to identify derogatory language in a collections database. We joined forces with Veronika Post, a data science graduate student from the Harvard Extension School, with the goal of making it easier for museum staff to find and address derogatory terms in collections databases.

We used a dataset of 1 million records from Harvard University Herbaria’s Global Biodiversity Information Facility Integrated Publishing Toolkit. This dataset only contained plant specimens collected in the United States, ensuring that our investigation into derogatory terms in the English language would not be confounded by non-derogatory terms in other languages (e.g., negro in Spanish has a different connotation than in English).

Post used standard data science to conduct exploratory analysis. This discovery phase revealed interesting trends and insights in the raw data, such as peak collecting years and common localities. In one case, Post found that a simple typo in the location coordinates caused one collection site to be plotted in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. By running these analyses, Post could remove any incomplete or duplicate records and identify fields that could potentially contain derogatory terms in place names and descriptions.

Once this discovery phase was complete, Post narrowed the search to two Darwin Core fields called occurrenceRemarks and locality. The Darwin Core schema provides standardized field names and definitions to describe biodiversity specimens. Using a list of eight derogatory terms selected by our group based on previous interactions with herbarium specimens, she used scripts to comb through 1,098,484 records with 71 fields of data.

Post extracted the records in which these terms appeared in the occurrenceRemarks or locality fields in a matter of minutes. In practice, this could save museum staff significant time finding, flagging, and updating records with derogatory terms that have been published using the recommended solutions and internal best practices.

Expanding to Include Bias and AI

While our initial project focused on derogatory language in natural history collections using the Darwin Core standard, our next step is to dig deeper into art and cultural history databases to discover more obscure types of bias. Even museums that have adopted Describing Archives: A Content Standard (DACS) and other similar protocols to standardize cataloguing and description practices have found that unintentional biases persist in their cataloguing efforts. These biases can manifest in many ways, from the selection of terminology to the framing of historical contexts.

In collaboration with the Harvard Art Museums and a newly onboarded data science student, we will continue to focus on “dirty,” non-standardized fields, like object Remarks that contain a wealth of information added by various museum staff over decades. These fields often include extended descriptions, context, provenance details, and other annotations that have not been standardized but offer a richer understanding of the artifacts.

Using sophisticated natural language processing (NLP) models to parse and analyze this unstructured data, we can identify specific words or phrases, detect patterns, and extract meaningful insights from the Remarks fields. This approach will not only help us manage the volume of data but also improve the accuracy and depth of our analyses. By automating the identification of derogatory or biased language, we can systematically revise and update our records, ensuring they reflect contemporary institutional values and respect for all represented cultures.

We are also exploring sentiment analysis, which uses NLP to determine a text’s emotional tone. By surfacing and analyzing these overlooked entries, we can begin to redress historical imbalances and reshape how collections are understood—both within the institution and by the public.

Today, digitization must evolve to be more inclusive, accurate, and sensitive to the origins and meanings of the collection histories, ensuring accessibility and institutional transparency. As museums continue to prioritize the practice of ethical stewardship, collection staff must not overlook the potential of digital collections to disseminate harmful ideologies through uncontextualized derogatory language.

Want to dive deeper? In the AAM Member Resource Library, you can explore even more about AI and digital content in museums.

» Related Resources

Resources

Laura Briscoe, et al., “Shining Light on Labels in the Dark: Guidelines for Offensive Collections Materials,” Collections, Oct. 12, 2022, pp. 1–18

doi.org/10.1177/15501906221130535

Alicia Chilcott, “Towards Protocols for Describing Racially Offensive Language in UK Public Archives.” Archival Science, vol. 19, no. 4, 2019, pp. 359–76

doi.org/10.1007/s10502-019-09314-y

Jonathan Kennedy, Harvard University Herbaria: All Records, Occurrence dataset

doi.org/10.15468/o3pvnh

John Sheridan, “Digital Archiving: ‘Context Is Everything,’” The National Archives Blog, April 19, 2018

blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/digital-archiving-context-everything/

Ryan Schmidt, et al., “Identifying the Collector Practices that Shape Spatial, Temporal, and Taxonomic Bias in Herbaria,” preprint from EcoEvoRxiv

doi.org/10.32942/X2432N

Madeline Schill (msschill@fas.harvard.edu) is Collections Fellow at the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University in Boston, Massachusetts.

Kathy Jones (kathy_jones@harvard.edu) is Director of Museum Studies at Harvard Extension School.