This article first appeared in the journal Exhibition (Fall 2025) Vol. 44 No. 2 and is reproduced with permission.

Alma Thomas (1891–1978) was an American artist, educator, and community organizer who developed her distinct form of abstract painting, and was her most prolific, in her later years. Hearing Thomas recount this moment of inspiration, one would not imagine that as she sat gazing out the kitchen window into her garden she was also experiencing a debilitating bout of arthritis and the onset of chronic pain. Her work does not reflect her discomfort. Instead, the luminous canvases this moment inspired burst with bright colors, sparking joy and wonder (fig. 1).

As Thomas painted throughout the 1960s and ’70s, the Cold War raged, John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. were assassinated, and the fight for civil rights gained momentum. A deeply involved member of her community, and a Black woman who spent her youth in the Jim Crow South, Thomas was no stranger to what she called “the ugly things in life.” And yet, art was a space of rest and restoration for her; a space where one could step away from these difficult realities and embrace the healing power she found in the beauty around her:

I’ve never bothered painting the ugly things in life. People struggling, having difficulty. You meet that when you go out, and then you have to come back and see the same thing hanging on the wall. No. I wanted something beautiful that you could sit down and look at. And then, the paintings change you.[i]

When the Denver Art Museum (DAM) became a venue for Composing Color: Paintings by Alma Thomas from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the core exhibition team challenged itself to create a visitor experience that honored Thomas’s belief that art could improve well-being.[ii] The team’s interpretive specialist (an author of this article) saw an opportunity to layer inclusive design practices, including specific interventions for rest, into the experience plan. It was essential to the team that those who related most to Thomas’s life—Black audiences, disabled audiences, and older audiences—felt comfortable and welcome in the exhibition space.[iii]

Throughout the exhibition’s development, the team sought inspiration and guidance on how to implement inclusive practices from colleagues in Lifelong Learning and Accessibility. The DAM has long been dedicated to supporting visitor well-being, and the Learning and Engagement (L&E) department has distinguished itself by deeply exploring new lenses through which visitors of all ages and abilities can connect with art and creativity. For the past 10 years, the Lifelong Learning and Accessibility division within L&E has focused on employing universal design (UD) principles to support exhibitions, programs, and spaces to be usable by all, including people with disabilities; and utilizing well-being outcomes to design programs for older adults.[iv]

The division’s expertise in these areas of accessible design and designing for well-being supported the exhibition team’s creation of a visitor experience plan that honored the big idea in Thomas’s work: there is a restorative power in beauty for both society and the self.

The Connection Between Arts, Health, and Well-Being

A growing body of research supports what Thomas seemed to instinctively understand over 50 years ago: art is a powerful tool for promoting health and well-being. A 2019 World Health Organization report analyzed more than 3,000 case studies supporting the health benefits of the arts and found that engaging with the arts (both viewing art and actively creating it) played a major role “in the prevention of ill health, promotion of good health, and management and treatment of illness across the lifespan.”[v] Engaging with art can reduce stress, improve focus, improve communication skills, and help individuals process emotions.[vi]

Spending time analyzing an artwork can stimulate both conscious and unconscious brain functions in substantial and long-lasting ways (fig. 2). Creative expression also engages the brain’s neuroplasticity (the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new connections and pathways), which can support people’s ability to adapt to new experiences and to heal from injuries.[vii]

Creative activities have been found to be especially powerful tools for improving the well-being of people with disabilities and older adults because arts participation fosters creative self-expression (of one’s internal state) and the outward production of something tangible and unique. This can result in increased self-efficacy and self-determination.[viii] For older adults, participating in creative pursuits can support outcomes of personal growth, increase connectedness, enrich positive emotions, and improve their sense of pride and self-worth.[ix]

Moreover, findings of this work on well-being seem to align with work in the fields of decolonization and antiracism, where ideas around radical rest have grown in prominence with the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. In 2016, activist Tricia Hersey founded the Nap Ministry, which she describes as an organization focused on “rest as a radical tool for community healing.”[x] “It is not about fluffy pillows, expensive sheets, silk sleep masks or any other external, frivolous, consumerist gimmick,” she writes in a 2022 blog post. “It is about a deep unraveling from white supremacy and capitalism . . . rest pushes back and disrupts a system that views human bodies as a tool for production and labor. It is a counter narrative.”[xi]

The concept of self-care and well-being as an indispensable component in the fight against institutional oppression is not a new one. Queer, Black activist Audre Lorde famously spoke of self-care as a form of resistance in her 1988 book of essays A Burst of Light. “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence,” she writes, “it is self-preservation and that is an act of political warfare.”[xii]

Within this context, rest is not passive, but an active and sometimes radical choice to prioritize self-care and community. Think back to the last time you rested:

- Did you have a choice of where, when, or how you could rest?

- Did anything interrupt or stop you from that rest?

So often, the right to rest without being perceived as lazy is only awarded to the very wealthy and/or very privileged. For those who hold nondominant identities—people of color, people with disabilities, and older adults, to name a few—rest can be difficult to come by in public spaces.

We know that art can be restorative. As spaces that display art and culture, it follows that museums should also be places for rest and renewal. But this is not the case. Oftentimes exhibitions are tightly packed, with narrow pathways unmanageable for mobility devices; artworks and labels are inaccessibly placed (too high, too low); and exhibition information is provided only in a visual format (often in tiny font and with low contrast).

Many museums see themselves primarily as stewards of objects of historical or social significance and their chief concern, as a result, is to collect, display, and interpret those objects for the perceived benefit of their visitors. This paternalistic approach decenters visitors’ needs when inside a museum. Rather than asking what they need to enjoy their visit and be comfortable in an exhibition space, or what could help focus their attention on works of art, too many museums install artworks in an idealized, one-size-fits-all way that requires visitors to change themselves in order to participate (or causes them to skip the experience entirely).

At a fundamental level, this ingrained neglect of visitor comfort reflects the societal practice of prioritizing productivity over comfort. This philosophy extends to our free time: in the museum, ostensibly a space of leisure, it is almost assumed that you will become tired—your feet will hurt, your back will ache, but the pursuit of culture will ultimately be worth it.

This phenomenon, known as museum fatigue, has been documented for over 100 years. In 1916, Benjamin Ives Gilman photographed visitors at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (where he worked) bending over or craning their heads to read exhibition labels or engage with artworks. Gilman advocated for more accessible displays of artworks and interpretive materials, arguing that “an inordinate amount of physical effort is demanded of the ideal visitor” and that “as at present installed, the contents of our museums are in large part only preserved, not shown.”[xiii] More recently, professor Stephen Bitgood has argued that museum fatigue is actually a combination of several phenomena including physical and mental fatigue and also object satiation, information overload, cognitive load, and competition between exhibition elements.[xiv]

And yet, as anyone who has worked on developing an art museum exhibition can tell you, adding seating is often an afterthought—a begrudging acquiescence to the reality of the human body. And even when it is incorporated, it is often far from ideal in fostering a sense of comfort. Take the quintessential museum bench (fig. 3). This unobtrusive fixture of hardwood or leather generally lacks a back or arms and is designed to fade into the background until explicitly sought out by a visitor in need.

This marginalization of physical rest encapsulates ableist attitudes toward well-being and comfort in the built exhibition environment, which run counter to Thomas’s philosophy.[xv] The goal in Composing Color was to create an experience where rest was a natural part of the exhibition, not a break from it. The team aimed to center visitor well-being by creating an exhibition where rest was framed as a part of, not a break from, the gallery experience, and where the accessible design of the show maximized the restorative power embedded in the artwork.

Inclusive Design Components

To inform the design of Composing Color, the exhibition team grounded itself in research and drew upon both the DAM’s recently developed older adult well-being outcomes and the principles of universal design.[xvi] These guiding principles helped the team translate Thomas’s belief in art’s connection to well-being into specific exhibition elements.

Well-Being Framework

From 2018 to 2022, the DAM investigated creative aging, uncovering five key well-being behaviors that could be supported through the design of programs and spaces at the museum.

Five Behaviors for Well-Being

- Be Active

Opportunities to create; opportunities to engage in a sensory experience. - Take Notice

Close-looking, asking questions, making observations. - Keep Learning

Trying new experiences; learning something new. - Connect

Sharing stories and experiences with others; relating to personal histories and memories. - Be Generous

Sharing time and expertise; giving a kind word; offering support.

Universal Design Principles

Universal design (UD) is a human-centered approach to design that places the fundamental needs of people at the center of any experience. In 1997, a working group of disabled and nondisabled architects, designers, and researchers out of North Carolina State University developed a set of principles to guide the design of environments, products, resources, and communications that can be used by a wide variety of people with a wide range of abilities, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.[xvii]

Principles of Universal Design

- Accommodating

Designed for everyone, regardless of age, ethnicity, gender, mobility, or circumstances. - Inclusive

Everyone can engage easily, safely, and with dignity. - Welcoming

Removes barriers that might exclude some people. - Flexible

Can be used in different ways by different people. - Convenient

Requires little effort for everyone to use. - Realistic

Balances people’s needs by offering more than one solution (one size may not fit all). - Understandable

Easy for everyone to understand and use. Use different modes (pictorial, verbal, tactile) for redundant presentation of essential information. - Responsive

Considers what people say they need and want.

UD recognizes that if an environment is “accessible, usable, convenient and a pleasure to use, everyone benefits.”[xviii]

The experience plan for Composing Color translated the five well-being outcomes into specific exhibition design experience goals that were then layered with UD principles:

- Have a restorative experience with art that creates space for liberatory joy.

Be active through intentional moments of rest with seating that is convenient and responsive to needs.

- Feel immersed in Alma Thomas’s “love comes from looking” way of seeing.

Keep learning about Thomas’s creative process through interactive activities that are accommodating, inclusive, and convenient to use. Connect to personal histories and share stories through supplemental reading material that is understandable and flexible.

- Be inspired to take notice of the simple things that provide joy and beauty.

Take notice of beauty through interpretive activities that are inclusive, flexible, and understandable in their approach.

Tying the exhibition’s experience goals to the principles of UD and known well-being outcomes ensured that the radical potential of rest remained at the center of our exhibition design.

Designing for Well-Being: A Case Study

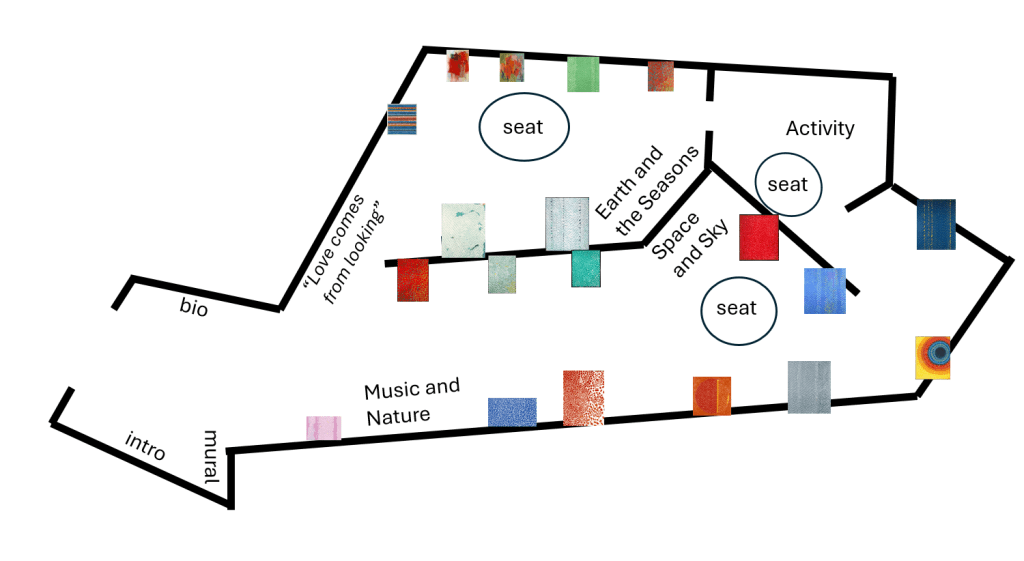

Armed with the learnings and support of the Lifelong Learning and Accessibility team, the exhibition team embarked on designing an exhibition that encouraged visitors to connect, take notice, be active, and keep learning through key design elements (fig. 4).

Lessening Cognitive Load

Among the phenomena Bitgood identifies as contributing to museum fatigue is cognitive load, which can be reduced by simply limiting the number of elements in an exhibition and by organizing them in clear and scannable ways so that visitors are able to control their experience.[xix]

Composing Color was naturally well-suited for a slower pace. The checklist included only 19 paintings in a gallery of around 5,200 square feet that was kept open to give people and objects more space to breathe. However, even 19 paintings—one after the other on neutral walls—could easily become monotonous and contribute to object satiation and decreased attention. To help balance this, we punctuated the exhibition with large-scale murals that delineate sections, helping visitors better navigate the space and make choices on what information they do and do not want to engage with (fig. 5).

Encouraging Rest

Key to encouraging well-being was the addition of three seating zones in the exhibition. The goal was to evoke the restful, welcoming atmosphere of domestic sitting rooms (intro image). To encourage visitors to take their time in these spaces, we augmented them with materials they could actively peruse: a children’s book on Alma Thomas for intergenerational groups, for example, and a photo album of the artist to help encourage a personal connection with Thomas.

Limitations to the exhibition budget meant we could not purchase new seating for this show. We were able to find a unique solution by partnering with DAM’s development department, which helped us pursue an in-kind donation from Denver-based company Furniture Row. The seating this company provided not only allowed us to serve audiences in Composing Color but also filled an important gap in our exhibition furniture holdings—providing seating that is easy to get in and out of, has back support, and isn’t too deep. It has already been reserved for use in multiple future exhibitions and will contribute to building more accessible exhibitions long-term.

Invitation to Play and Create

Most DAM exhibitions include a hands-on interpretive activity, and Composing Color was no exception. While we always hope these moments will be enjoyed by a variety of visitors, they are often aimed at children. For Composing Color,we decided to intentionally design for intergenerational audiences, with the goal of fostering active engagement and creativity in a wider range of visitors.

Inspired by Thomas’s story of watching light filter through the foliage of her garden, the activity allowed visitors to make their own “light scape” using a light box and various translucent materials. Taking inspiration from the Lifelong Learning team’s creative aging programs, we chose to use more sophisticated materials in this activity: instead of translucent sensory toys made for light boxes, we sourced vintage silks and lace scraps, leaf skeletons, and agates (fig. 6).

![] A woman in a sunhat, purple tee-shirt, jean shorts, and running shoes smiles a large, open-mouth smile to her companion, a man in a baseball cap, casual collared shirt, rumpled shorts, and running shoes. The couple appear to be in their 50s or early 60s. The man is standing while the woman sits on a cushioned chair at a light table. The walls surrounding them feature projections of the objects on the light table: purple and green translucent agate stones, a cigarette, and dark shapes that may be dried leaves. Together, these objects create abstract-like patterns on the walls of the gallery.](https://www.aam-us.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Fig-6.jpg?resize=1024%2C683)

Evaluation

To assess the effectiveness of these design choices, we conducted a visitor study using two primary evaluation methods:

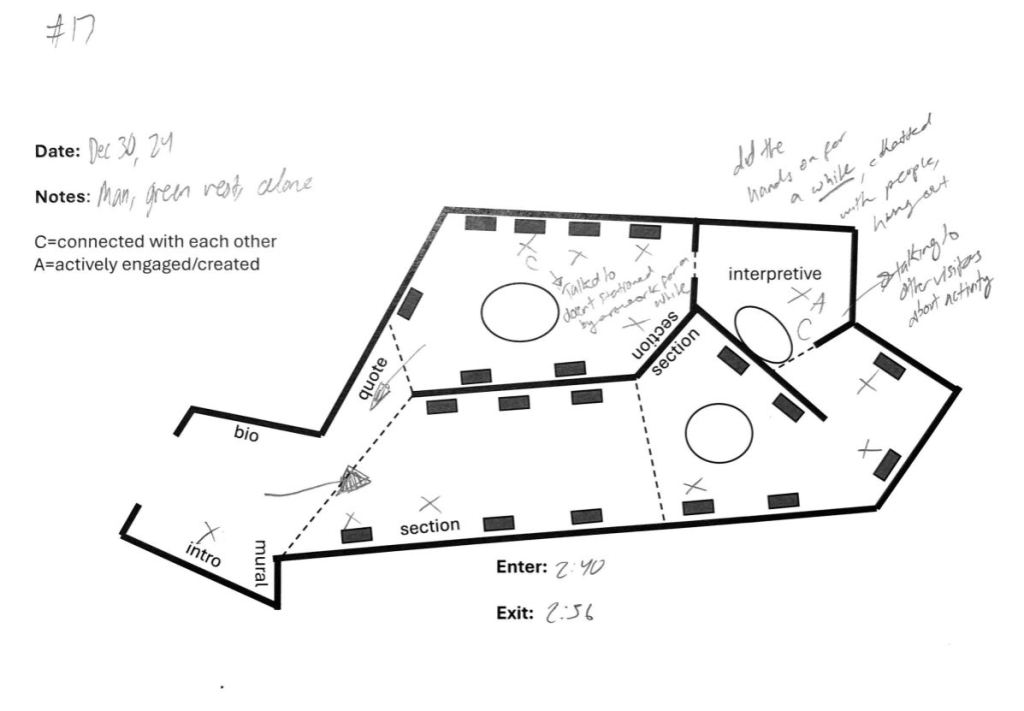

- Tracking Visitor Behavior: Thirty visitors were observed throughout their visit. Observers noted where they stopped; how long they spent in the exhibition; moments of active engagement; and instances of social connection. There were a total of 27 exhibition elements that visitors could engage with, including 19 artworks, five longer texts, three seating areas, and the light scape activity (fig. 7).

- Intercept Interviews: Eight visitors were interviewed upon exiting the exhibition to gather qualitative insights about their experience.

Findings

We found that visitors demonstrated behaviors known to contribute to well-being, and that many interviewees specifically noticed and appreciated the different design choices we made.

In their seminal 2001 study, researchers Jeffery and Lisa Smith observed 150 visitors looking at six separate paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and found that the average time spent looking at art by these visitors was 27.2 seconds.[xx] In the nearly 25 years that have elapsed since this study, many others have reinforced that visitors spend, on average, around 30 seconds per artwork in a museum setting.[xxi]

In Composing Color, visitors spent an average of one minute per exhibition element they engaged with—roughly twice the typical duration. This number was calculated by dividing the total time each visitor spent in the exhibition by the number of exhibition elements they stopped at. A stop was defined as a pause with both feet facing the element for more than five seconds. Ten of the 30 observed visitors used the seating zones, as did three of the eight interviewees, with one sharing, “my back is struggling today, it’s too much standing.” An additional five of the eight interviewees mentioned that they appreciated the exhibition’s open, less dense layout:

I loved that it wasn’t crowded and you could take your time.

This is just right because you can really appreciate each piece, just spend time.

Because creative aging is active, not passive, we also took note of when visitors used exhibition materials. Of the 30 observed visitors, 14 actively engaged with supplementary content or participated in the making activity. Two interviewees, both older adults, noted that they generally don’t use these types of interactives in museums but chose to this time because, as one said, “playing with light was too fun to pass up.”

Not every visitor who stopped at the interactive area chose to participate, including several interviewees. When asked why, interviewees invariably responded that the area was already in use by another visitor, often a child, and so they chose to watch.[xxii]

Two-thirds of observed visitors had at least one social interaction in Composing Color (fig. 8).[xxiii]Of these, 13 came to the show with a companion, but not all their social interactions were with that companion. People were observed chatting with other visitors and with museum staff.[xxiv] Interestingly, visitors who engaged socially during the exhibition had much richer experiences when compared to those who did not. For instance, the 10 visitors who had three or more social interactions in the gallery spent an average of 17.7 minutes in the exhibition and stopped at 53 percent of exhibition elements. This is significantly higher than visitors who had no social interactions, who spent an average of 6.9 minutes in the show and stopped at 34.1 percent of elements. It seems that encouraging social connection within exhibitions is mutually beneficial for visitor well-being and the museum’s own engagement goals.

While it was harder to measure (through observation) whether visitors were learning new things and becoming inspired as they went through the exhibition, all interviewees chose to share things they learned or were inspired by. For example:

I loved how she sees things. I just was saying to my partner here that I felt like we were looking through the leaves at the sky, or through the snow to the pond, or from the airplane to the flowers.

This suggests not only inspiration and learning, but also social interaction around exhibition themes. Six of the eight interviewees explicitly expressed curiosity by asking the interviewer further questions or asking where they could buy the catalogue to learn more.

Interviewees also personally connected with Thomas’s story—particularly her spirit, determination, and way of looking:

Having that context of her life and the inspiration that she took and everything, I feel like it really changed my perspective.

She was determined to be who she wanted to be, and whatever the situations were relative to her race, her gender, didn’t seem to stop her.

In one exciting interview, a visitor even connected directly to the theme of creative aging:

The text that’s there about changing style as a reaction to changing life circumstances and abilities was really interesting. . . . I don’t know, I’m getting older and have to think about that stuff.

It seems that, at least based on this small sample of interviewees, visitors understood and connected with the main themes of the exhibition and left energized and curious, not exhausted and drained. This is further supported by the fact that eight visitors went through the show more than once, doubling back to ask a question or look at a piece a second time. This behavior suggests leaving the show with energy to spare.

Conclusion

In staging Composing Color, the DAM embraced Thomas’s radical insistence that beauty and rest are vital—and, at times, revolutionary—acts. By weaving UD principles with a well-being framework, the exhibition did more than display art: it redefined how audiences engage with it. Through spacious galleries, inviting seating, multisensory interactives, and open invitations to notice, learn, connect, and create, the visitor experience honored both Thomas’s vision and the restorative potential of museums. We offer the following advice to others seeking to promote rest and well-being in their exhibitions:

Create Opportunities for Visitors to Take Notice

- Lessen the cognitive load of looking. Lower the concentration of objects per square foot. Integrate visual breaks in content (like using vinyl murals or super-graphics between galleries and overview paragraphs at the beginning of introductory and thematic panels).

- Integrate rest. Position rest as a part of the exhibition, not a break from it, offering seating areas that are intentional in their placement and appearance, as well as flexibleand responsive(fitting all shapes and sizes, ideally with adjustable arms and back) and convenient (little effort to find inside the exhibition and use).

Create Opportunities for Visitors to Be Active

- Provide interactive activities. Explore key exhibition concepts (processes, materials, etc.) through hands-on experiences that are accommodating(usable by all shapes, sizes, and considering mobility devices), inclusive(presented in multiple modalities), and convenient to use (clear instructions in multiple languages and modalities). Focus on incorporating high quality materials.

Create Opportunities for Visitors to Connect and Keep Learning

- Provide historical, social, and cultural context through supplemental materials that are understandable(available in different modalities and formats; e.g., photo albums, picture books, online resource links, etc.) and flexible (can be used in a variety of ways).

These design choices helped us honor Thomas’s legacy—not just as an artist, but as a person who understood the power of art to heal, connect, and uplift marginalized communities. In centering well-being, we created a museum experience that aligned with her vision, ensuring that those who would have most related to her life could fully enjoy and engage with her work. We believe that honoring well-being and inviting visitors into the radical potential of rest is one powerful way to move beyond accessibility toward true inclusion.

Danielle Schulz is Associate Director of Lifelong Learning and Accessibility at the Denver Art Museum in Denver, Colorado. DSchulz@DenverArtMuseum.org

Karuna Srikureja is Associate Director of Learning and Engagement at the Honolulu Museum of Art in Honolulu, Hawaii. KSrikureja@HonoluluMuseum.org

[i] Alma Thomas, quoted in Alma W. Thomas: Everything Is Beautiful, Jonathan Frederick Walz and Seth Freman, eds. (Yale University Press, 2021), 61.

[ii] The core team included curator Rory Padeken, curatorial assistant Hadia Shaikh, project manager and designer Eric Berkemeyer, and interpretive specialist Karuna Srikureja.

[iii] The authors intentionally switch between identity-first and person-first language throughout this article to acknowledge the different ways people with disabilities self-identify.

[iv] Creative Aging programs use the arts to empower adults 55+ to develop a greater sense of purpose, boost physical and cognitive abilities, deepen connections to community, and enrich overall quality of life as we age.

[v] Daisy Fancourt and Saoirse Finn, “What is the evidence on the role of the arts in proving health and well-being? A scoping review,” Health Evidence Network Synthesis Report no. 67 (2019): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553773/.

[vi]“How the Brain is Affected by Art,” American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine, accessed March 15, 2025, https://acrm.org/rehabilitation-medicine/how-the-brain-is-affected-by-art.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Crystal Finley, Access to the Visual Arts: History and Programming for People with Disabilities (Vanderbilt Kennedy Center, 2013), 3, https://vkc.vumc.org/assets/files/resources/ArtsManual-P1-adj.pdf.

[ix] Denver Art Museum, “Art Museums and Healthy Aging: A Creative Aging Tool Kit,” 2023, https://d26jxt5097u8sr.cloudfront.net/s3fs-public/2023-11/FINALCreativeAgingReport_RD3.pdf.

[x] “About,” The Nap Ministry, accessed March 15, 2025, thenapministry.wordpress.com/about/.

[xi] “Rest is anything that connects you to your mind and body,” The Nap Ministry, last modified February 21, 2022, https://thenapministry.wordpress.com/2022/02/21/rest-is-anything-that-connects-your-mind-and-body/.

[xii] Audre Lorde, A Burst of Light (Firebrand Books, 1988), 131.

[xiii] Benjamin Ives Gilman, “Museum Fatigue,” The Scientific Monthly,vol. 2, no. 1 (January 1916): https://www.jstor.org/stable/6127.

[xiv] Stephen Bitgood, “Museum fatigue and related phenomena,” **JVA Interp News** 4 (November–December 2015): https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304944315_Museum_fatigue_and_related_phenomena

[xv] Ableism is defined as discrimination and prejudice against people with disabilities due to the belief that typical abilities and bodies are superior.

[xvi] Denver Art Museum, “Art Museums and Healthy Aging.”

[xvii] “About Universal Design,” Centre for Excellence in Universal Design, accessed March 15, 2025, https://universaldesign.ie/about-universal-design/the-7-principles.

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] Bitgood, “Museum fatigue and related phenomena,” 4.

[xx] Jeffery K. Smith and Lisa F. Smith, “Spending Time on Art,” Empirical Studies of the Arts,19, no. 2 (2001): https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279390313_Spending_Time_on_Art.

[xxi] Lisa F. Smith, Jeffery K. Smith, and Pablo P. L. Tinio, “Time Spent Viewing Art and Reading Labels,” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 11, no. 1 (2017): https://www.researchgate.net/publication/296475094_Time_Spent_Viewing_Art_and_Reading_Labels; Claus-Christian Carbon, “Art Perception in the Museum: How We Spend Time and Space in Art Exhibitions,” i-Perception 8(2017): doi.org/10.1177/2041669517694184.

[xxii] Evaluation occurred close to the winter holiday season and during the well-attended exhibition, Wild Things: The Art of Maurice Sendak,which was just upstairs from Composing Color, likely contributing to the crowding we observed at activity stations.

[xxiii] It is unclear what the baseline is for social interactions in museum exhibitions, so we cannot say if visitors were more socially engaged in Composing Color than is typical.

[xxiv] Brief interactions including yes or no questions unrelated to artwork (e.g., Are you ready to go? Where’s the bathroom?) were not included in our analysis.