This article first appeared in the journal Exhibition (Fall 2025) Vol. 44 No. 2 and is reproduced with permission.

Developing an accessible exhibition requires collaboration between curators, departments, artists, audiences, and institutions. The Office for Civil Rights (OCR) at the U.S. Department of Education defines accessibility as affording a person with a disability “the opportunity to acquire the same information, engage in the same interactions, and enjoy the same services as a person without a disability in an equally integrated and equally effective manner, with substantially equivalent ease of use.”[i] This article will center on a case study from the Walker Art Center, a multidisciplinary contemporary art center located in Minneapolis, Minnesota, that welcomes over 700,000 guests[ii] every year through public programs, an outdoor sculpture garden, a state-of-the-art cinema and theater, and over 65,000 square feet of exhibition space.[iii]

The Walker’s strategic plan articulates an expectation that staff “center audiences in the planning and presentation of programs,”[iv] and when making institutional decisions. In alignment with this approach, and in response to visitor feedback, the authors developed a tailored set of guidelines and processes to produce accessible exhibitions that go beyond legal compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Because the Walker defines accessibility as a process that requires collaboration between staff, artists, and communities, the guidelines were developed and refined through consultation with d/Deaf and disabled staff[v] and community members, as well as the Institute for Human Centered Design (IHCD). The latter has collaborated on projects “advancing the role of design in expanding opportunity and enhancing experience for people of all ages, abilities and cultures through excellence in design” since the late 1970s and has been working with the Walker on several of our accessibility initiatives.[vi]

The guidelines and related processes were also designed in alignment with the Walker’s unique built environment. Even with this institutional specificity, the authors believe that insights gleaned from this project (in particular strategies to ensure organizational adoption and shared accountabilities) will be useful to others as they examine their museum’s processes and assumptions in an effort to expand their own accessibility.

As most people who work in large organizations know all too well, change—even much needed and much desired change—is often slow to happen. Phases of this project were completed at very different organizational inflection points and occasionally happened concurrently. The Walker’s senior leadership has been very supportive of this project, providing working time and institutional financial resources necessary to develop, test, and refine the guidelines in consultation with artists and D/deaf and disabled community members. In this case study we will discuss in detail the three stages of the project from identification of the need for Walker-specific accessible installation guidelines, to drafting and revision, and finally, implementation. We will share four strategies to facilitate consensus and shared accountability that we feel contributed to the success of this project:

- Adopting a cross-departmental working group model

- Identifying recurring points of tension and bottlenecks in exhibition-making processes and creating targeted interventions

- Creating shared terminology

- Providing opportunities for embodied learning for staff members and input from community members with disabilities

Identifying the Need

As a museum that works with living artists and has a particular interest in hybridity and multidisciplinary practices, no two exhibition-creation trajectories at the Walker are the same. Bespoke environments, custom display mechanisms, and even the fabrication of artworks themselves are not uncommon collaborations between artists, the Walker’s Exhibition Installation team, and curators. This results in very different visitor experiences across exhibitions. As a result, the development of an installation manual became an Exhibition Installation Department priority in 2020 and 2021 during the period of museum closure due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with emphasis placed on documenting the high standards and best practices of a well-established and regarded team and establishing consistent standards across our spaces. The initial hope was that the installation manual would be a useful tool in training the next generation of Walker installation preparators.

Walker visitor feedback consistently identifies barriers for visitors with mobility limitations in our building architecture as well as a lack of consistency in exhibition design features, including overlapping and loud audio, lack of accessible gallery seating, and disorienting gallery presentations. Like many museums, before work on Walker-specific guidelines began, staff referenced the Smithsonian Guidelines for Accessible Exhibition Design when reviewing exhibition floorplans for accessibility.[vii] When interpreting those guidelines for the unique built environment of the Walker, we found ourselves with divergent understandings that created barriers to taking a consistent approach to exhibition design.

As a result, the authors and their senior leaders saw the potential to expand the scope of the initial draft installation manual into a broader project capable of addressing the accessibility needs that had been identified across exhibitions and which often start with the development of an exhibition floorplan.

Staff realized that in order to develop a comprehensive set of guidelines that addressed the concerns outlined above, expertise from departments across the museum was needed, necessitating the convening of a cross-departmental working group. This core group is comprised of the authors of this article. The relative parity of our positions, along with detailed expertise spanning different areas of the organizational structure, was invaluable to the long-term success of the project. The working group also exemplifies a key insight: planning for accessibility is the entire staff’s responsibility. Instead of locating accountability with one individual or department (in our experience, often an education or visitor services department), the guidelines define expectations not only for all staff who contribute to exhibition development, but also for our work with artists.

Developing the Guidelines

Research

Many museums have been working for years to apply an accessibility lens to exhibition development. The first phase of our work was to review literature on this subject and to reach out to colleagues to reciprocally share learnings. The Walker’s initial draft guidelines were informed by:

- Smithsonian Guidelines for Accessible Exhibition Design

- Design for Accessibility: A Cultural Administrator’s Handbook

- National Museums of Scotland’s Exhibitions for All: A Practical Guide to Designing Inclusive Exhibitions

- National Park Service’s Accessibility & Universal Design Standards

Conversations with colleagues at institutions including the Museum of Modern Art, Denver Art Museum, and Portland Art Museum were extremely helpful, as was reviewing Walker visitor feedback and the 2022 journey-mapping study, “A Welcoming & Confident Visitor Experience.”[viii] Artist Carolyn Lazard’s Accessibility in the Arts: A Promise and a Practice was an invaluable resource in identifying desired outcomes for visitors.

Language Shifts

When drafting the Walker’s guidelines, the working group continually met to review new sections and to discuss the potential impacts of new standards along with scenarios that had come up in past exhibitions that provided moments of learning. One of the first examples of a recurring source of tension that we identified was divergent interpretations of terminology used in the Smithsonian guidelines. Far from a drawback, we found these moments of disagreement highly productive. One example of language in the Smithsonian guidelines that staff continually grappled with was the definition of circulation route:

V. Circulation Route:

A. The circulation route within the exhibition must be accessible according to the requirements of the Smithsonian Guidelines for Accessible Design for Facilities and Sites.

B. The circulation route must be well lighted, clearly defined, and easy to follow.[ix]

While the Smithsonian guidelines expand upon circulation route throughout the document, at the Walker this baseline definition was historically interpreted in one of two ways: 1) as primarily referencing hallways and other constricted passageways; 2) as any path a visitor might take to travel through the open architecture typical of our gallery spaces. To build consensus around an approach that was relevant to our institution, the working group drafted more descriptive language:

Path of Travel or Approach: In an exhibition, the path of travel or approach is defined as the open floor space available to access and view/experience artwork on display. All art and non-art objects (e.g., furniture, benches, etc.) in an exhibition space should be placed so they are perceptible/detectable by a visitor as approached within the path of travel or approach.

Perceptible/detectable: An object is perceptible/detectable when its placement within the gallery provides multiple cues for a visitor to become aware of its presence in order to avoid contact. The display of artworks that are less perceptible/detectable should employ mitigation solutions to improve their perceptibility.[x]

“Cane detectability” is another example of language that had historically been interpreted differently across the Walker, resulting in different approaches across exhibitions. To facilitate shared understanding, we drafted an expanded definition that included an explanation of how people navigate using a cane, as well as a list of possible strategies to improve cane detectability for various types of artworks including gallery placement, bases/risers, gallery stanchions/detection rails, and tread tape. These strategies seek to promote and balance visitor experience, artwork safety, and aesthetic sensibilities that are based on the artist’s intent and are listed in the agreed upon order of effectiveness based on staff and visitor feedback, as well as observation of visitor behavior.

By including these discrete choices for how to address cane detectability and shifting language to facilitate shared understanding across departments, the manual foregrounds both the importance of consistent adoption and our understanding that accessibility is a conversation requiring active participation from all stakeholders.

Soliciting Feedback

In alignment with the Walker’s strategic plan, which centers audiences’ experiences of the art and programs we present, the working group developed several processes to solicit feedback from staff and disabled community members. This input helped us collaboratively determine key standards and refine the guidelines based on visitors’ experiences in exhibitions that had been installed based on iterations of the draft guidelines.

In 2022, as a first phase in our multistep process of soliciting input, we installed artwork in a vacant gallery to test various elements of the guidelines with our colleagues, including:

- Hanging height of 2D artworks

- Text size and label placement

- Circulation space around floor-mounted objects

- Seating (intro image)

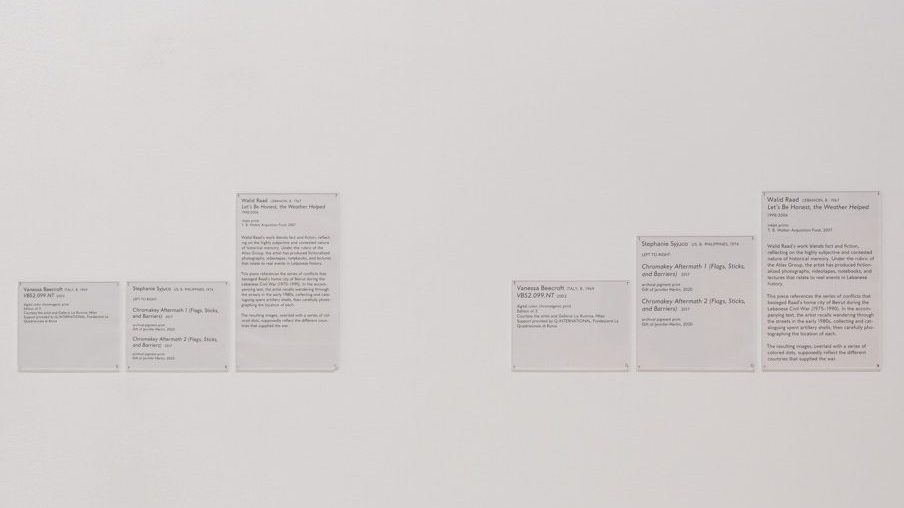

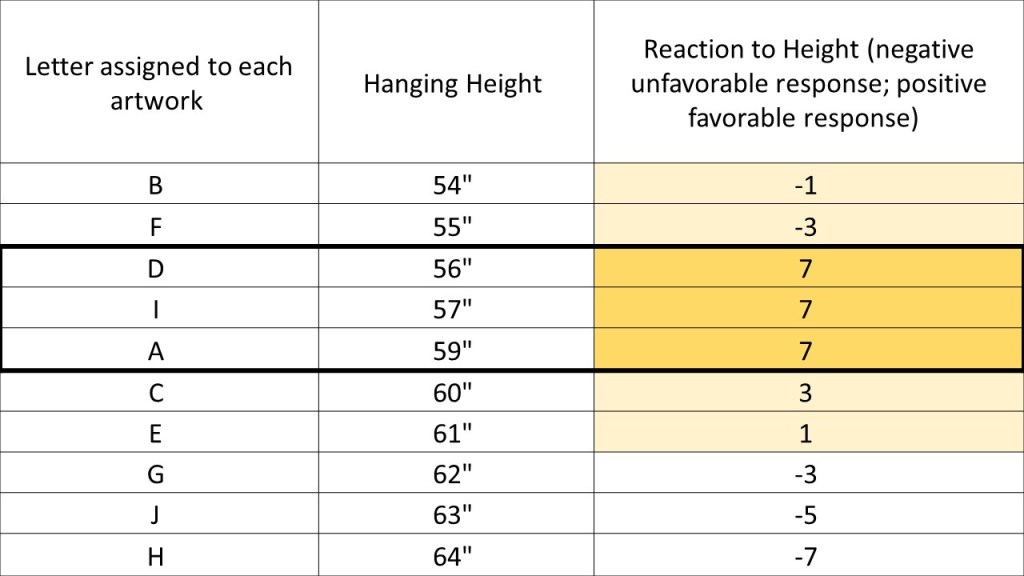

We then facilitated group conversations asking about 30 participants with and without disabilities from Visitor Experience, Public Engagement and Learning, Registration, and Visual Art to consider their experience accessing artworks when standing and seated, when far away and close-up, and when the gallery was crowded and less crowded. Written and verbal feedback collected at those sessions informed the manual’s standards for hanging height (fig. 1), label design and placement (fig. 2), and minimum dimensions for paths of travel.

The facilitated experience resulted in many key outcomes, including immediately recognizable and actionable moments of consensus. When presented with three different sizes of wall label, everyone agreed one was far too small—in fact, this had been our standard wall label size until that meeting. Immediately, we collectively made the decision to increase the size and have since received positive feedback from visitors about the change (fig. 3). Thanks to the feedback we received, we moved from a former standard of 16.5 pt over a leading of 20 pt at 6″ wide to 20 pt over a leading of 24 pt at 7″ wide.

Similarly, when asked to consider the hanging height of 2D artworks while seated and standing, participants broadly agreed that our standard hanging height should be lowered quite dramatically. While feedback on the evaluation forms was qualitative, the authors created a numeric, quantifiable way to rank the responses, which we then used to set our now standard hanging height: 58″ or lower from the floor to the center of the artwork (though this is variable based on size of the artwork) (fig. 4).

Walker staff have applied these revised guidelines to the design of exhibitions over the past several years, providing opportunities to measure their impact and efficacy in improving the experience for visitors with disabilities.

Next, the Walker partnered with Janice Majewski, Director of Inclusive Cultural Projects at the Institute for Human Centered Design to review our draft and provide feedback, ensuring compliance with the ADA and better centering inclusive design practices. Majewski’s comments emphasized the importance of consistency for visitors and helped us to streamline and clarify our language throughout the guidelines.

After incorporating Majewski’s revisions, staff began an ongoing process of partnering with disabled community members to solicit feedback on their experience. Partners visit the Walker when new exhibitions open and answer a standard set of questions designed to help staff understand how comfortable visitors feel in exhibitions, their experience navigating exhibitions, their sensory experience, and the ease with which they can access the art and interpretation. Though each person’s experience has differed, themes have emerged in the feedback including the importance of:

- Consistency (to help visitors understand where to locate interpretation, what they can and cannot touch, etc.)

- Contrast (for legibility and visibility)

- Allowing visitors to opt in or out of experiences with extreme sensory input (isolating loud volume, providing well-lit paths of travel, etc.)

As one visitor shared, “I am an art lover and want to be immersed in the exhibit experience of what is in front of me and not distracted by over light [exposure] and [as] a person with hearing loss, I still can hear the music or talking and was wondering where it was coming from which was interfering with [being] present at the display section I was in.” The feedback we collect generates future discussion and consideration as we continue to refine the guidelines based on new learnings.

Implementation

During implementation, which as noted above, often happened simultaneously with building consensus and revision, we focused on systemic changes to our processes, including:

- Generating mutually reinforcing milestones and checkpoints that distribute responsibility for centering accessibility across project teams

- Continuing to iterate, refine, and implement learnings in each new exhibition, instead of waiting for a final, authoritative document

Accessibility is a process, and because disability is experienced differently by each person—and each exhibition and artwork is unique—these guidelines are a place to begin a collaborative planning process with colleagues, artists, visitors, and partners. The structures and workflows we produced allow for continual learning and updating alongside exhibition-creation.

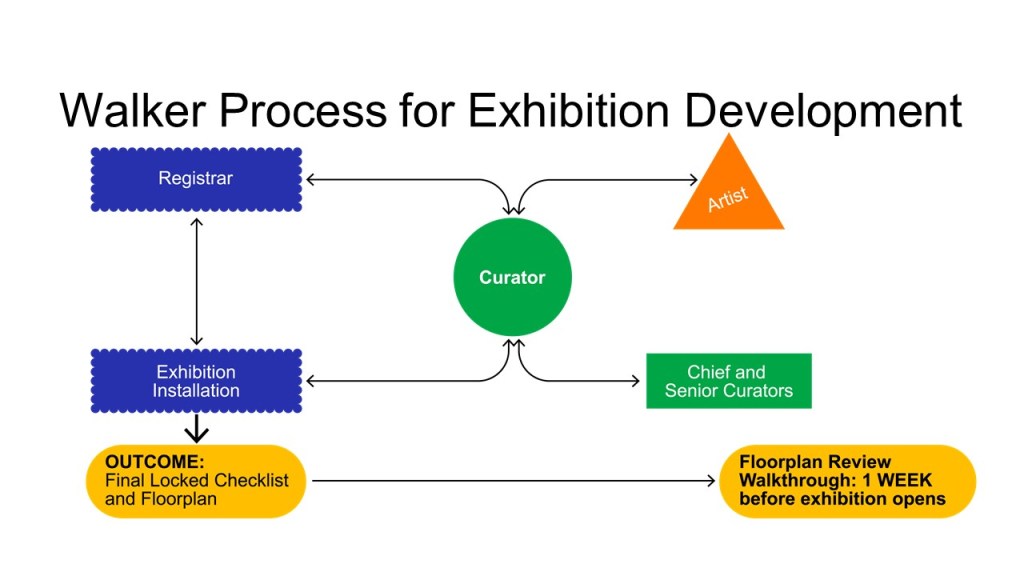

Our 2022 exhibition Paul Chan: Breathers allowed staff to partner with an artist to reconsider some of our long-running exhibition-production practices and paved the way for our new processes. With this exhibition, as was the practice at the time, the curator and artist worked collaboratively to finalize a floorplan before it was shared with other staff members for input (fig. 5). Once it was shared more broadly, the Associate Director of Learning and Accessibility immediately raised several questions. The exhibition contained three bodies of work displayed directly on the gallery floor: Arguments (artworks comprised of electrical cords plugged into walls and other objects), Nonprojections (projectors that sit on the floor and do not display traditional moving images), and Breathers (reminiscent of fan-powered inflatable tube dancers, these playful works move in unexpected ways). In the initial floorplans, the curator and artist had placed most Arguments and Nonprojections in the middle of the galleries, which would have required visitors to navigate through and around arrangements of cords, creating potential tripping hazards. As part of the conceit of the work is that these objects are not precious, placing them on risers or pedestals was not an option.

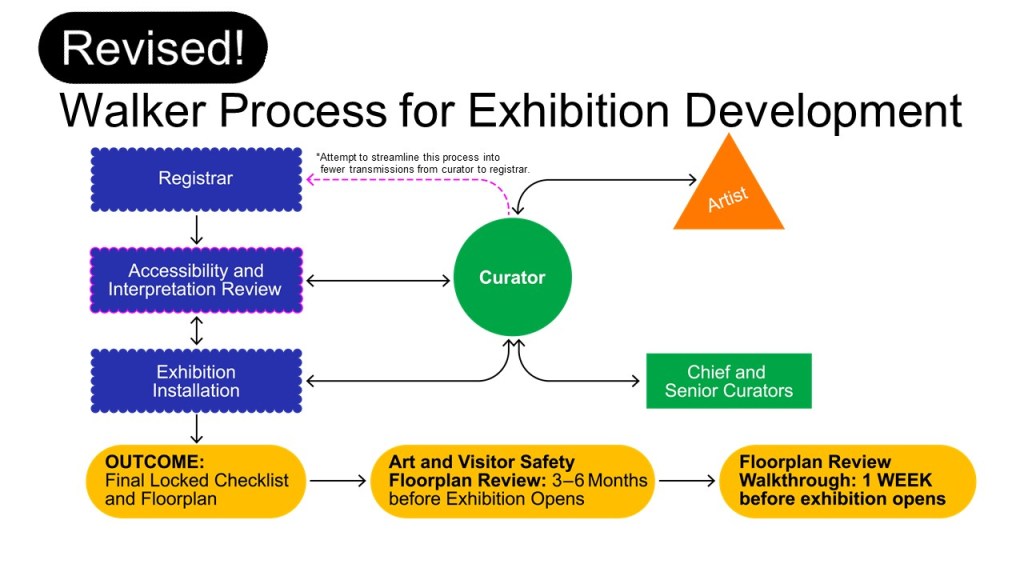

The revision necessary to arrive at the final floorplan helped our working group come to a key insight: it is much more difficult to retroactively update a floorplan than it is to give clear guidance and partner with the curator and artist to consider accessibility at the outset. While the curator and the artist were both very receptive to feedback, the floorplan creation process ended up being a protracted one. To ensure a smoother process and a more accessible result moving forward, we provided the curators and Exhibition Installation team with our working accessibility guidelines and added an accessibility discussion as a prerequisite part of floorplan creation (fig. 6).

Now, before any physical, scaled artwork models or digital SketchUp files are created for the artist and curator, the curator must discuss the working checklist with our Manager of Interpretation and Associate Director of Learning and Accessibility. During this review, these key stakeholders ask questions and make recommendations that remain tied to the exhibition throughout its development. The Associate Director of Learning and Accessibility also attends monthly exhibition-production meetings with the curator, Registration, and Exhibition Installation where accessibility is discussed as planning and production progresses. By making this accessibility review precede floorplan creation, potential areas of concern are highlighted and taken into consideration before anyone becomes too invested in a particular placement. Additionally, this step provides an opportunity to partner with the artist to consider accessibility at the forefront of the process and reinforces that accessibility is everyone’s responsibility. Instead of having concerns come up at the end that require last-minute changes and potentially cause moments of tension, these discussions are always present and attended to during the formation of the floorplan.

In the case of Paul Chan: Breathers, the artist and curator worked together to adjust the placement of the floor-mounted artworks, moving works that posed a tripping hazard to the edges of the gallery and creating a path of travel through the center of the space that was clear of obstacles. While cords remained arranged on the floor, they were discretely secured to the terrazzo to reduce the risk of tripping if someone did step on them (fig. 7).

Next Steps

Our ability to progress such a nuanced and time-consuming project has been possible because we recognized early on that a polished final document was not necessary to implement and test improvements. This is not to say that a proofed and approved document complete with illustrations is not the goal (as we write this, final proofreading and diagram creation is well underway). If we had waited for “final” approval or a perfectly designed PDF, we would have waited too long. Incisive changes and midstream process-correction based on audience feedback have been important parts of the process that have made subsequent exhibitions better.

Additionally, because our understanding of disability is constantly evolving, it is important to frame this work as a process of learning and revision, rather than as the creation of a static “final” document. Walker staff understand that we will continue to apply new learnings and to make adjustments in response to visitors’ experiences and artists’ partnerships—though this is challenging in a field built upon authoritative standards, precise workflows, and long-standing norms. As a next step, we hope to support curators and artists in partnering to consider how to ensure all visitors can access and make meaning from the work on view. This involves thinking with artists about how to create accessible sound environments and how to provide access to audio in moving-image and other multimedia work, something that, historically, has not been centered in museum and gallery presentations of work by living artists and will require a culture shift in the field’s approach.

Our core insights can be broadly understood under three interdependent spheres of activity: the process of building consensus, defining accountabilities across departments, and collaborative implementation. While these spheres are clear to us in hindsight, we want to highlight that this was an organic process that required flexibility and consensus-building instead of neatly pre-determined steps. We say this to provide reassurance to other museums and organizations who are attempting to move beyond ADA compliance and striving to improve accessibility. As you consider how you might approach or further this work at your own institution, we recommend considering the following:

Building Consensus

- Who would be key partners and allies in initiating and executing this work

Figure 1 (staff, community, etc.)? - What shared language is needed to make sure staff are working toward the same goal?

Cross-Departmental Accountability

- What accessibility concerns are most often raised by D/deaf and disabled

visitors to your institution? If this information is not available, how might you gather it? - What kind of intervention in your process might facilitate a consistent consideration of audiences and accessibility (who needs to be part of discussions and when)?

Collaborative Implementation

- What would you need to make change at your institution (budget, buy-in, training, etc.)?

- When is the right moment to address these concerns in your institution’s exhibition-planning process?

- What feedback loops can you create to ensure continual improvement?

Accessibility is a process, not a destination, and building broad-based group consensus and workable process improvements is essential to making meaningful and lasting change in any organization.

Doc Czypinski is Associate Director, Exhibition Installation, at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, Minnesota. doc.czypinski@walkerart.org

Sarah Lampen is Associate Director of Learning and Accessibility at the Walker Art Center. sarah.lampen@walkerart.org

Erin McNeil is Associate Director of Curatorial Affairs at the Walker Art Center. erin.mcneil@walkerart.org

[i] “What Does Accessible Mean?” NC State University, accessed August 7, 2025, dro.equalopportunity.ncsu.edu/miscellaneous/what-does-accessible-mean/.

[ii] Walker Art Center, “Fiscal Year 2023–2024 Annual Report,” p. 60.

[iii] Walker Art Center, “About,” accessed August 7, 2025, walkerart.org/about/.

[iv] Walker Art Center, “2022–2026 Strategic Plan,” p. 14.

[v] Language related to disability is evolving, and people have different preferences. In an effort to honor people’s preference between identity-first and person-first language, the Walker uses both throughout this case study. Some people who are Deaf identify as a linguistic minority, so the phrase D/deaf and disabled has been employed to encompass the entirety of the communities the Walker works to center in its accessibility work. For more information on language, consult the National Center on Disability and Journalism’s Disability Language Style Guide: www.ncdj.org/style-guide.

[vi] “Mission,” Institute for Human Centered Design, accessed March 28, 2025, www.humancentereddesign.org/about-us/mission.

[vii] Smithsonian Institution, Smithsonian Guidelines for Accessible Exhibition Design (Smithsonian Accessibility Program, 1996, 2010).

[viii] HGA, “Researching a Confident Visitor Experience at the Walker Art Center,” HGA News, December 12, 2022, www.hga.com/walker-art-center-visitor-experience.

[ix] Smithsonian Guidelines for Accessible Exhibition Design, p. 7.

[x] Walker Art Center, “Walker Art Center’s Installation Guidelines for Accessible and Inclusive Exhibitions,” unpublished working doc., p. 5.