This article originally appeared in the March/April 2010 edition of the Museum magazine.

Hey, wait a second! Who’s driving the bus?

Like a character out of Speed-that crazy 1990s movie with the speeding bus and the beautiful woman-this particular driver is a little heavy on the horn. A road hog! He clutches the big wheel, grinning madly, and waves his passengers gaily aboard.

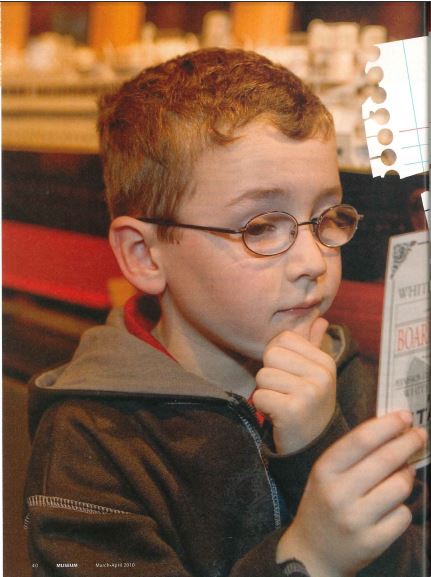

He’s 2-year-old Nicholas Quigley, and he sometimes drives his mother crazy. But today he’s driving a stationary, life-size commuter bus at Philadelphia ‘s newly remodeled Please Touch Museum, a place where kids also get the wheels of their brain whirring and whizzing.

“I tell my mother that I feel bad for taking him here every weekend,” says Kathryn Quigley, clutching a red vinyl firefighter’s jacket. “We should do something educational,” she protests. “But then my mother tells me, ‘It is educational!”‘

Listen to your mother, Kathryn.

Children’s museums, and a growing number of adult-oriented museums, as well, are increasingly tapping into visitors’ brains to create more effective learning experiences that linger in their memories. Thanks to current brain research, how to do that isn’t such a mystery anymore.

In neuroscience labs across the globe, brain researchers are studying, scanning and mapping our neural circuitry, using imaging technology that wasn’t available 20 years ago. Their work has already influenced traditional classrooms, where today’s teachers often consider the power of personal connections to create better retention of their lessons. Now, it can also inform the way museums operate.

These scientists tell us that multi-sensory activities-like that bus or the nearby “River Adventures” exhibit, where Nick will drench a fleet of rubber ducks-can create more effective learning experiences. At the same time, so do emotional connections.

HOW WE LEARN

Your brain is about the size of a cauliflower-a smallish, squishy, very unappetizing cauliflower-but it acts more like a computer. Inside, there are about 100 billion nerve cells called neurons that transmit signals to each other, sort of like wires in that fancy MacBook.

Some neurons carry information from the outer parts of your body {like your muscles or skin) to the central nervous system, while others take directions from your brain in the opposite direction. Many are involved in sensory systems like vision or hearing or touch. When you hear something, for example, that sound is picked up by receptors in your ear, usually hair cells, and then the neurons code that information and send it on its way.

Depending on what kind of information it is, it goes to specialized parts of the brain before it reaches the cortex or higher processing centers. New imaging techniques, which measure the brain’s response to different information or stimuli, tell us that some areas of the brain respond to visual stimuli, others to smell. There’s one part that lights up when an object moves toward you or if you touch an animal’s face.

Aaron Seitz, an assistant professor at the University of California, Riverside, has focused on multi-sensory learning through experiments that measure whether a combination of sensory information like sight and sound can teach basic tasks more effectively. What he’s gathered has important implications for museums and museum professionals.

First, he points to research in multi-sensory education fields that indicates the limited capacity of the brain to process one kind of stimulation at a time. Basically, “there’s only so much visual information that you can deal with,” Seitz says. He recalls a study in which people looked at pictures of lightning. At the same time, some also read information about how lightning works and others listened to that information read aloud. Generally, the people who looked at the pictures and listened to the information learned and remembered more than those who relied on vision alone.

“It was visual information overload,” he says. “You can take in much more information if some of it’s visual, some of it is audio and some of it is tactile.”

This makes sense when you consider what’s happening in the brain. “When you’re looking at a visual stimulus, the large parts of the brain that use auditory information aren’t going to be involved at all,” Seitz explains. “If your goal is to stimulate the brain, you can’t do that with visual alone. And if you’re worried about fatiguing part of the brain, then the things that fatigue the visual processes are going to leave the auditory processes unfatigued.”

As a child, Seitz spent three very long days at the Louvre. “It kind of wears you down after a while,” he laughs. Maybe if he had been hooked up to an audio companion or allowed to actually touch the Venus de Milo, he might have eagerly embraced a fourth day.

“This is a new field of research. There’s not a huge amount of neuroscience studies that directly prove that if you first look at a bunch of paintings and then you go into a room where you can actually feel sculpture that it would increase your learning, but there’s a lot of reason to expect that it would,” Seitz says. “There’s also a lot of reason to believe you’d be willing to spend more time in that museum.”

ALL HANDS ON DECK

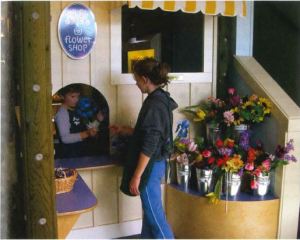

At the Hands On Children’s Museum in Olympia, Wash., it’s thinking like Seitz’s that will inform the new $18 million facility opening in late 2011. Already, the existing museum is all about touch, says Kathy Irwin, exhibits manager. “Children learn through play, emulating and role modeling and being able to do that on a tangible level,” she says.

In the “Hands On” market exhibit, kids gather eggs. In its “Working Waterfront” exhibit, they build barriers on the water table, redirecting the rush and flow. “You can just see that they’re learning,” Irwin says. “They’re looking at what they’re feeling, they’re repetitive in their spaces, they’re fully engaged in what they’re playing with.”

The new museum will feature many favorite exhibits from the old building, but it will include a new emphasis on nature and outdoor spaces-a natural focus for its location on the Puget Sound. Young visitors will build their own boats and take them home, and also interact on a large-scale fishing boat.

Meanwhile, at the Please Touch, Willard Whitson, vice president of exhibits and education, takes his inspiration from Howard Gardner, the Harvard University professor best known for his theory of multiple intelligences. According to Gardner, there is no one kind of intelligence. Instead, there are seven, including linguistic, spatial, logic-mathematical and kinesthetic.

“What we’re trying to do-philosophically, educationally- is [honor] the notion that people learn in different ways. There is no one route to intelligence nor one single measurement of intelligence,” Whitson says. “For very young visitors, part of the spatial kinesthetic is understanding how they relate in the environment and how elements in the environment relate to them. And that’s where touch comes in.”

Inside the museum, just past the giant hamster wheel that demonstrates what momentum means, there’s a 44- foot rocket ship. This is one of Whitson’s favorite exhibits.

First, his visitors put together airplanes out of simple, brightly colored inter-locking foam shapes, then they hook their creations to a kind of bicycle chain on the rocket and hand-crank them toward the sky, where they glide gracefully down. Or not so gracefully, depending on the young engineer’s skill.

Shouts from the floor follow the flights, and the youngest children attempt to catch the flyers with widespread arms. Older kids, Whitson notes, might have a more intellectually sophisticated experience, asking questions like, “Why didn’t my plane fly? What can I do differently?” Others set up competitions to see whose invention can stay airborne longest. “We are deliberately trying to debunk the notion that learning is painful,” Whitson says. “Learning is fun!”

Other senses can play a role in learning, as well. While Seitz and his collaborator, Ladan Shams of the University of California, Los Angeles, have shown that sight and sound work effectively together, some other research points to the power of smell. One interesting finding about the smell from the University Medical Center, Chicago: Older adults who struggle to identify common odors may be at greater risk of developing problems with learning and memory.

Researchers also are exploring the role of movement in learning. A University of Chicago study earlier this year showed that students who gesture during their math lessons did much better at solving those problems. They more easily retrieved old information from their brain’s storehouses and remembered new information. “This study highlights the importance of motor learning, even in nonmotor tasks,” the lead author, psychologist Susan Goldin-Meadow, wrote in the journal Psychological Science.

Of course, moving stuff and touching stuff is easy in a children’s museum, where not much is bolted down. In other, more traditional museums, where the mission is to “collect and protect,” as Whitson says, it’s understandable that curators may not want to underscore a lesson on pointillism with a sticky swipe across Seurat’s Grande Jatte and Circus canvas.

But models and replicas are popular substitutes, even with adults. Check out the scene on a Saturday morning in the great ape house at the Smithsonian National Zoological Park in Washington, D.C., where a zoo volunteer shows off a swatch of orangutan hair. Young visitors eagerly stroke the long red tresses, and then their parents shyly, seriously follow.

“Oh, it’s not soft at all!” one remarks, with surprise. She turns to the back of her son: “Honey, you want to touch this again?”

THE EMOTIONAL BRAIN

Outside the Little Rock Central High School national historic site, where the National Park Service operates a popular visitor’s center, Amanda Jones snaps a photo of the writing on the wall. It says, quoting from the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution: “[No state shall] deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Tucking her camera into a shoulder bag, Jones, who is visiting Little Rock from northern Arkansas, reflects on her visit to the site. “It’s kind of emotional,” she says, gazing toward the famous facade of the red brick high school where nine black high school students strode past an angry white mob in September 1957.

Inside, hours of black-and-white footage shot by newsmen of the time, as well as contemporary interviews with the Little Rock Nine and other witnesses to public school integration, stream across screens. Old memories, recorded and retold at desk stations with black phone earpieces, are haunting.

“I remember asking my mother why the school bus passed by my sister and I,” recounts one of the nine, his voice rising. “You just did what you were told,” says another, helplessly.

Their voices, their gazes-through the camera into the conscience of visitors-do elicit an emotional response. Fear, regret, then maybe relief or pride. And that, say brain researchers, makes what they’re saying so much more memorable.

Amanda Jones is not likely to forget this afternoon. Frankly, her hippocampus wouldn’t allow it. There are three main areas of your brain. Closest to your spinal cord and common among all vertebrates, you’ll find the central core, which controls basic life functions like breathing. That’s your lizard brain, you might say. Under your skull, closest to the top, there’s the cerebral cortex-the spongy stuff that directs higher-order cognitive thinking. That’s the gray matter that helps humans rule the Earth.

In between, you have the limbic system, which includes the amygdala complex and hippocampus-the heart of emotion and memory, respectively-and the area where new information is converted to memory. (Without a hippocampus, you’d be like an Alzheimer’s patient, whose disease strikes the hippocampus first.) These two areas are closely linked, researchers have found.

But the three main areas aren’t walled off. There also are close connections between the limbic system and the fancy-thinking cerebral cortex, which grew out of the limbic system. And more of these connections go upward than downward, giving the emotional brain a great deal of influence over how we think, writes Joe Givens of the Human Givens Institute.

Fear is a particularly effective emotion when it comes to learning. The howl of a coyote is a ready reminder to avoid a certain section of woods, right? But fear is probably not what you’d want to evoke in a museum visitor, and too much fear is actually terrible for learning. Fear, as well as stress, releases in the brain a hormone called cortisol, which actually kills hippocampal neurons in high levels. This is part of the reason why bullying is such a terrible thing in schools. Not only is it socially harmful, but it actually prevents learning, too.

Better for everybody are endorphins-the hormones released during exercise, while music is played and during other positive experiences. Endorphins actually help you solve problems. And that’s probably why studies show that students who get more physical exercise-and, more recently, students who practice yoga during school-do better on tests.

“The mode that best helps people to learn is relaxed alertness,” says Candace Pert, author of Molecules of Emotion: Why You Feel the Way You Feel and a frequent lecturer on the effect of emotion on learning. This phenomenon is so intuitively understood-of course, I won’t do well if I’m terrified!-even children understand the implications. In a University of Washington study, researchers asked students to predict the academic ability of children who just experienced various emotions. For example, if a little girl loses her teddy bear on the way to school, will she do well on her math test? Students understood that levels of interest and effort would affect performance, and they described for researchers how emotions might affect their attention and concentration.

THE PERSONAL EXPERIENCE

Evoking emotion and creating memories isn’t just about making people happy or sad. It’s also about making them think the content is personally relevant to them.

What emotions have always done is “guide us in what to pay attention to,” Pert says. “The whole point of emotions, what evolution designed emotions for, is survival. If you’re fearful and you run away, it’s because it’s going to help you survive …. If a museum can make that personal connection, if its [content] is not some abstraction-it’s really about you, the visitor-then it’s grabbing you at a place that’s very deep.”

One of the first museums (and still one of the most effective) to personalize its content was the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., where visitors are issued identity cards of real Holocaust victims and encouraged to follow in their footsteps through the museum.

The practice was unusual when that museum opened in 1993, but it’s used more widely these days to the same effect. Consider the traveling exhibit “Titanic: The Artifact Exhibition,” which tells the story of the doomed ship, passengers and crew through objects salvaged from the bottom of the sea. Upon entering, all visitors receive boarding passes that look exactly like actual Titanic tickets. On the back is the name and description of a real passenger, whose identity the visitor can embrace. At the end of the self-guided tour, they learn their fate.

“It immediately gives them a sort of identity,” says Mary Bridges, director of communications at the Milwaukee Public Museum, which hosted the exhibit last spring for more than a quarter-million visitors. And Bridges has evidence in her office that visitors take that identity to heart. “We have a register at the end where people write down their feelings-every week I get piles of paper delivered to me,” she says. Pulling one from the top, she reads a note left by a young woman: “It’s absolutely incredible and mind-blowing to see the artifacts .. . . I feel so horrible about the people who lost their lives!”

The exhibit also includes a virtual lifeboat created on the floor by ceiling lights and an ice wall kept at 28 degrees, the

temperature of the North Atlantic on that fateful night. “Our exhibit staff here is so fabulous-that ice wall is in a dark room with stars. It’s really a little bit eerie …. We encourage people to put their hands on it, see how it feels and how long they can keep their hand there,” Bridges says. All in all, the reaction to “Titanic” has been tremendous, she says. “People love it. The connection is unbelievable.”

But personalization doesn’t have to be as ambitious as issuing new identities to your visitors. It can be as basic as this lesson on integration at the Little Rock center. There, a glowing table asks, “Were you included in ‘We the People’?” and then directs visitors to “touch a portrait to find your place in the new democratic republic.” (Amanda Jones, a white woman, may have been disappointed to learn that her rights in the new nation were not so very many.)

Or it can be as simple as letting that kid take the wheel.