American museums still struggle with the legacy of race.

This article originally appeared in the November/December 2010 edition of the Museum magazine.

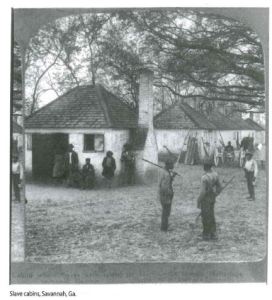

Early in my career, I crafted an exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History that explored the role and history of American slavery. I traveled throughout the American South searching for an extant slave cabin that I could use in the exhibition. Ultimately, I found one in the rice-producing area of the Wacamaw Neck near Georgetown, S.C. There I met Mr. Johnson, the grandson of a slave who had resided in one of 12 cabins on a “slave street” from the 1850s until her death in the 1930s.

Mr. Johnson talked about how the slaves did a “hard sweep” that eliminated the grass and weeds that were home to vermin. Then we walked to the side where the fireplace was located, and he spoke about how slave children helped maintain chimneys to prevent fires. And then we moved to the rear of the cabin where he explained how slaves used that space to grow crops supplementing food provided by the owners.

Finally, I walked to the fourth side, but Mr. Johnson did not follow me. After repeatedly asking him to accompany me, I demanded to know why he left me alone on that side of the cabin. He said that he would not move in my direction because the area was full of poisonous snakes.

After I stopped running, I asked why he did not warn me. He said that everyone around here knows the history of that spot. And then he said, “People need to remember not just what they want, but what they need. It pains the ancestors when we forget.” His words—”people need to remember”—have never left me.

Ultimately, Mr. Johnson called for people to remember not simply out of nostalgia but because of history—especially African American history—provides useful tools and lessons that help us navigate contemporary life. The best museum presentations can help people find that meaningful and usable past. Yet, not everyone believes that this nation should remember—especially when these memories include and are fundamentally shaped by African American history and culture.

The notion that African American history has limited meaning should be a concern for all Americans. In this essay, I want to explore why the interpretation and preservation of African American history and culture in museums are so important and relevant for an America still struggling with the legacy and impact of race. What are the challenges that museums face as they struggle to help people remember a fuller, richer and more complex history?

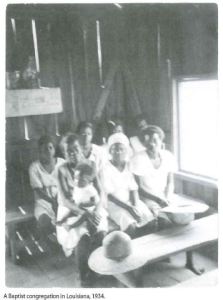

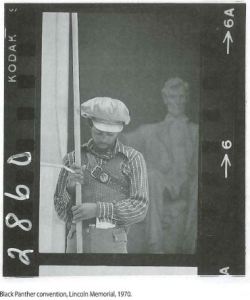

You can tell a great deal about a country or a people by what they deem important enough to remember, what they build monuments to celebrate and what graces the walls of their museums. The United States traditionally revels in Civil War battles or founding fathers, with an occasional president thrown into the mix. Yet, I would argue that we learn even more about a country by what it chooses to forget. This desire to omit—to forget disappointments, moments of evil and great missteps—is both natural and instructive. It is often the essence of African American culture that is forgotten or downplayed. And yet, it is also the African American experience that is a clarion call to remember.

A good example of this nexus of race and memory is one of the last great unmentionables of public discourse about American history—the story of slavery. For nearly 250 years, slavery not only existed but was one of the most dominant forces in American life. Political clout and economic fortune depended upon the labor of slaves. Almost every aspect of American life—from business to religion, from culture to commerce, from foreign policy to western expansion—was informed and shaped by the experience of slavery. American slavery was so dominant globally that at one point 90 percent of the world’s cotton was produced in the American South. By 1860s, the monetary value of slaves outweighed all the money invested in this country’s railroads, banking and industry combined. And the most devastating war in American history was fought over the issue of slavery.

Few institutions, however, address this history for a non-scholarly audience. And there are even fewer opportunities to discuss—candidly and openly—the impact, legacy and contemporary meaning of slavery. The history of slavery matters because it has shaped so much of our complex and troubling struggle to find racial equality. There is a great need to help Americans understand this. And until we use the past to better understand the contemporary resonance of slavery, we will never get to the heart of one of the central dilemmas in American life—race relations.

African American culture provides inspiration, sustenance, and guidance, giving people tools and paths to help them live their lives. In a 1997 speech, for example, Nelson Mandela said that in his 27 years in prison on Robben Island, one of the things that gave him strength and substance was the struggle for racial equality in America. He spoke passionately and eloquently of how American abolitionists such as Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass inspired him and helped him to believe that freedom and racial transformation were possible in South Africa.

As America continues its internal debates about who we are as a nation and what our core values are, where better to look than through the lens of African American history and culture? If one wants to understand the notion of American resilience, optimism or spirituality, where better than the black experience? If one wants to explore the limits of the American dream, where better than by examining the Gordian knot of race relations? If one wants to understand the impact and tensions that accompany the changing demographics of our cities, where better than the literature and music of the African American community? African American culture has the power and the complexity needed to illuminate all the dark corners of American life, and the power to illuminate all the possibility and ambiguities of American life. Whether we write, preserve or exhibit history or consumer culture, we must do a better job of centralizing race.

A final reason why African American history and culture are still so vital, so relevant and so important is because the black past is a wonderful but unforgiving mirror that reminds us of America’s ideals and promises. It is a mirror that makes those who are often invisible more visible and it gives voice to many who are often overlooked. It is a mirror that challenges us to be better and to work to make our community and country better. But it is also a mirror that allows us to see our commonalities. It is a mirror that allows us to celebrate and to revel but also demands that we all struggle, that we all continue to “fight the good fight.”

So how well have museums done, and what are the challenges that they face today? W.E.B. DuBois famously said that the problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line. One of the key challenges that 21st-century cultural institutions face is how to wrestle effectively with, and cross, that color line. If museums are truly to be institutions that the public admires and trusts, then they should expend the political and cultural capital, take the risks to help their visitors find a useful, usable, inclusive and meaningful history that engages us all.

No one can deny that change has occurred. In the late 1970s, the National Air and Space Museum (NASM) was embroiled in a minor controversy about race. African American veterans of World War II, especially members of the all-black fighter squadrons known as the Tuskegee Airmen, voiced their concerns that NASM intentionally underplayed the important contributions of black aviators in the war. Soon a few members of Congress, most notably Sen. Ted Kennedy, inquired about the role of African American history at the Smithsonian Institution. In response, NASM asked several African American staff members to allow their likenesses to grace mannequins that would be placed in the museum to increase the “black presence.” Ultimately, these figures were positioned in airplanes or exhibit settings that were so high up or so far removed that the only way the public could view this increased presence was through binoculars purchased in the gift shop.

Clearly, African American history is no longer at the fringe in today’s museums. For those who study or who are interested in the African American past, there have been many imaginative exhibitions over the last 15 years that have stretched the interpretive parameters and challenged the tenor and the color of historical presentations in museums.

The past decade has been a period of growth, excitement, and possibility; museums as diverse as the National Museum of American History, the New-York Historical Society, the Chicago Historical Museum, the Oakland Museum and the Henry Ford Museum have wrestled creatively with African American subject matter. Even more important and instructive is the array of smaller institutions like the Please Touch Museum in Philadelphia, the Geneva Historical Society, the Levine Museum of the New South and the Mexican Fine Art Center and Museum in Chicago that have sought to give local meaning to the issues of race in America. And African American museums in Detroit, Los Angeles, Chicago and New York all continue to explore the impact, legacy and continuing importance of race in American life. As a consequence of these activities, the public has experienced exhibitions that explored African American migration from the South to the North, like Spencer Crew’s “From Field to Factory”; slavery in New York; ethnicity, race and adolescence in the Chicago Historical Museum’s “Teen Chicago”; representations of race in American art; the photography of James Van Der Zee and Gordon Parks; urbanization and community development; and the intersection of race and gender. The research and exhibition of African American life in museums have contributed a vibrancy and relevance that has invigorated many of the nation’s cultural institutions and sparked useful collaborations between museums and communities. There is a sense of accomplishment and completion felt by many public historians.

While there have been great changes in whom and what museums interpret, it is much too soon to be satisfied with the American museum profession’s efforts in exploring African American culture. Often the rhetoric of change fails to match the realities of everyday life in museums. My major concern is that museums are too often crafting exhibitions that simply say, “African Americans were here, too,” rather than examining the complexities, interactions and difficulties of race in America. In essence, much of what institutions create today is better suited to the world of 40 years ago, when blacks, in the words of novelist Ralph Ellison, “were invisible men and women,” and whites needed to be reminded that African American history and culture mattered. Presentations for the 21st century need to better reflect the clashes, compromises, broken alliances, failed expectations and contested terrain that shape the perspectives of today’s audiences.

Despite two decades of substantive progress and change, whiteness is still the gold standard in museums. While there have been many exhibitions and many moments to celebrate, I am not convinced that these exhibitions have as far-reaching and as permanent an impact as one might believe. While many of these presentations introduced newer, more diverse audiences to cultural institutions, the relationships are not often nurtured or sustained. Often, museums “check off” the African American exhibition and return to business as usual once the exhibition has closed. And business, as usual, is celebrating whiteness.

So despite our successes, there is a need to move the presentation of African American culture in America’s museums to a higher level that embraces long-term change, includes a more holistic and diverse view of the African American experience, and recognizes the need for new paradigms and alternative structures that shape both the products and the process of exploring the black past in museums.

For museums to better explore and present African American culture, they must overcome or at least grapple with a few core challenges:

1) Transcending the Rosy Glow of the Past

Langston Hughes once wrote a poem that included these lines:

Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.

It’s had tacks in it,

And splinters,

And boards torn up

This poem suggests that the path to equality was not linear and not without setbacks and moments of defeat. Yet many of the exhibitions in our museums that explore America’s racial heritage view the past through a prism of optimism, a path of linear and inevitable progress that romanticizes African American history. The African American community is depicted as being composed of upwardly mobile heroes to whom racism and discrimination were simply obstacles that would eventually be overcome. While this often occurred, it was more the exception than the rule during much of America’s history.

What is lacking is a commitment to explore the full range of African American experiences, including the difficulties, the controversies, and the defeats. Too few museums wrestle effectually with the harsh realities of black life. Too many mention—but rarely explore in depth—issues of violence, arbitrary abuses of power, lynchings and the devastating effects of generations of poverty and discrimination. For every example of a Chicago Historical Museum or New York Historical Society that mounted exhibitions on lynching, scores avoided that subject. And for every attempt by museums such as the New Jersey Historical Society to explore the urban unrest of the 1960s, many other museums in cities affected by the long, hot summers of the 1960s simply remain silent.

I am not calling for museums to focus only on the difficult and the unpleasant or to depict African Americans as victims. I simply hope that museums provide visitors with a richly nuanced history that is replete with great joy and great sorrow and that helps visitors to see that museums do more than offer simple answers to the complex questions of the past.

2) Resisting Monolithic Depictions of the Past

When one reads African American literature, whether it is the urban poetry of Langston Hughes or the rich depiction of racial joys and sorrows in the plays of August Wilson—or when we tap our toes to Aretha Franklin, Sam Cooke or Run DMC—we are struck by the rich mosaic of African American life. In this literature and in this music, we are introduced to a black world that abounds with differences based on class, region, gender, color, education, and spirituality. Yet far too few exhibitions convey this rich diversity or explore the meanings of these differences for the audience. Rarely is this richness captured. In fact, most exhibitions explore the black community through the lens of the middle class. While the black middle class is central to our understanding of aspects of black life and aspirations, simply viewing that history obscures the full range of African American experiences. By resisting this urge, museums can help visitors better understand the conflicts, negotiations and shifting coalitions that are part of the black community. By exploring topics such as labor practices, burial practices and storefront religions, cultural institutions are more likely to provide a richer and a more complex view of the African American past.

3) Embracing Ambiguity

People often visit museums in search of uncomplicated narratives, simple answers to complex questions, and confirmation of memories and traditions. And far too frequently, museums have crafted exhibitions that have satisfied the need for celebration, comfort and closure. Our goal should be to provide opportunities for audiences to embrace and even revel in the ambiguities of the past. Historians know much about the complexity of the past and the nuances and agency that shape cultural interaction. Yet, museums are not as effective as they could be in conveying that ambiguity to the public. I would argue that one of the signs of successful exhibitions or programs is whether the audience becomes more comfortable with ambiguity and with complexity. This is especially germane when museums interpret African American culture.

4) Finding a “New Integration”

Brown v. Board of Education legally ended segregation in America in 1954· Yet Jim Crow segregation is alive and well in America’s museums, which seem comfortable embracing the notion of separate but equal when it comes to African American culture. Far too frequently, African American culture is segregated from the other more “mainstream” stories that museums explore. Either African American culture is interpreted as an interesting and occasionally educational episode that has limited meaning for non-African American visitors or it is trumpeted as a special attraction that is more exotic than instructive.

What is missing is a new synthesis-a “new integration”- that encourages visitors to see that exploring issues of race is essential to their understanding of American culture. Museums have been less successful when it comes to conveying the centrality of race in the construction of American national and regional identity. And they have often failed to help visitors understand that African American culture is a wonderful lens for understanding the American experience.

The key to this new integration is the creation of exhibitions that depict the interaction among African Americans and the broader society. These presentations would explore the clashes, the conflicts, compromises and cultural borrowing that is at the core of the American past. If museums do their job right, the public will see a duality that is evident in lines crafted by Langston Hughes:

I am the American heartbreak

Rock on which Freedom

Stumps its toe—

The great mistake

That Jamestown

Made long ago.

And yet, as the poet states in another poem, “I, too, am America.”

African American culture has a permanent home in America’s museums, but there is still much to do to reach the Promised Land. A former slave, Cornelius Holmes, was quoted as saying in 1939: “Though the slavery question is settled, its impact is not. The Question will be with us always. It is in our politics, in our courts, on our highways, in our manner and in our thoughts—all the day—every day.”

What a gift it will be when museums help the public understand that they are shaped and touched by African American history—all the day, every day.

Comments