This article originally appeared in the January/February 2012 edition of the Museum magazine.

Creating A Climate For Online Collaborative Learning

Online collaborative learning can take many forms. It can range from a blended learning course involving 20 participants to an online multi-institution conference involving 200 or more. But no matter what form online collaborative learning takes, there are some key factors or ingredients, that can increase the likelihood of success. Some of these factors are very concrete and tangible-such as the tools one might need to collaborate online. Other factors are less tangible but equally important, such as trust, respect and a willingness to take risks. But before examining these key factors, it is important to consider whether collaboration is the mode in which you need to be working.

Ways Of Working: Are We Always Collaborating?

Sometimes collaboration is not required in order to achieve your goal. Sometimes, rather than collaborating, people and organizations can work together in other ways—and sometimes they decide not to work together at all. A collaboration that truly builds on everyone’s contributions and ideas can be difficult, and collaboration done poorly can be less useful than not attempting to collaborate at all.

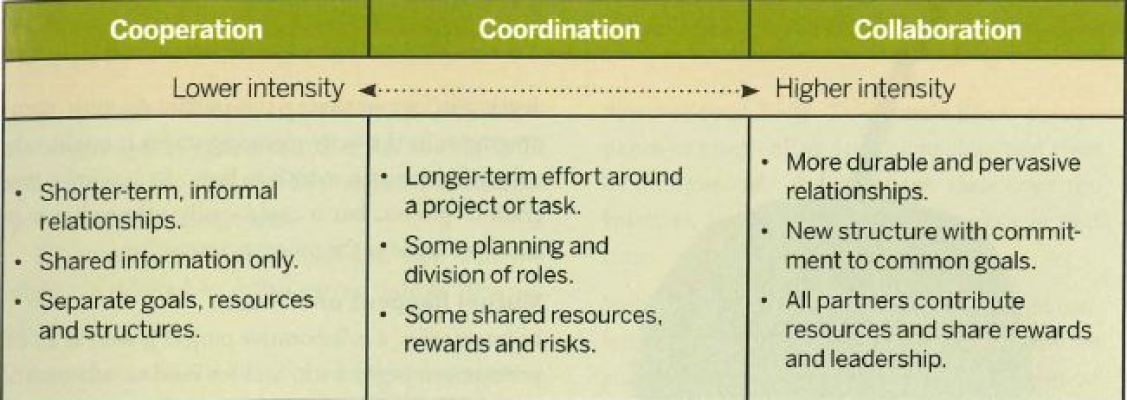

People can work together and relate to one another in very different ways and at different levels. As you consider what it might truly mean to collaborate, you should also examine the other ways that people can work together. Here are the “5 C’s” of how people (or even organizations) can relate to one another:

Competition

We have all experienced competition in some form or another, and sometimes in organizations, this can even be mistaken for collaboration. Some work and management models posit that best outcomes come about through competing entities. In our contemporary culture, competition is rewarded, and it can be difficult to think outside of this model. However, in the end, competition is often about win/lose relationships, and the entities are often operating with their self-interest in mind-not for the benefit of the public at large.

Consultation or Connection

This is about the ability and/or willingness to share our learning, experience, and expertise with others as a way to assist their planning efforts. Rather than working exclusively within one’s boundaries, it can allow for communication and some mutual support. However, consulting or connecting with one another does not guarantee that people will collaborate.

Cooperation

Through cooperation, we recognize our common interests and values, and we determine a way to work together. We can still retain our separateness, autonomy, and viability. This can sometimes involve stating or formalizing an agreement that serves our respective needs and ensures non-competition. Through cooperation, we might be able to balance our goals with the goals of others, but still retain our autonomy.

Coordination

Coordination means that we are consciously taking into account the activities of others when we are developing our own work and activities. This is about understanding the value of defining our “niche” and working with others to provide a continuum of services to meet the broader needs of our target population. We develop relationships with others that we hope will ensure non-competition around our particular area of work, and we provide and expect the same from others. Coordination does not mean that we share other aspects of our work, or even all of our resources. Coordination sometimes includes the sharing of physical spaces or assets. Coordination does not necessitate a shared interest in aligning and maximizing the results of both activities, a key element of any collaboration. Success is up to each individual part, and the greater, combined success is not a primary goal.

Collaboration

This means that we are truly coming together as separate entities to accomplish a common goal or purpose. This common goal can be better met through a collaborative process that brings together key stakeholders than through the efforts of a single entity. In other words, more can be achieved together than separately.

We set aside the tendency toward turf protection, and each individual or agency commits its resources and expertise.

A useful table to examine the differences between these ways of relating can be seen above.

True collaboration requires a commitment to shared goals, a jointly developed structure and shared responsibility, mutual authority, and accountability for success, along with the sharing of resources, risks, and rewards.

The People

Before considering the tools, the digital assets, the instructional design, and factors, the most important ingredient in any online collaborative learning is people. Who will be collaborating and toward what end? Who are the key stakeholders in your museum? Who will be involved from another museum or organization? Who else could be involved-teachers, students, parents, teens? As you consider who the key collaborators could be, you will want to consider their particular skills and strengths, why they may want to collaborate and any potential barriers to their collaboration.

Although online collaborative learning has a particularly democratic, flat structure in which everyone can contribute, this doesn’t mean that collaborators are without roles. It is important to consider what role each collaborator will play, what they can contribute, and how they may connect with others.

The Climate For Collaboration Online: Some Key Factors

Similar to an in-person collaboration, there are key factors that must be in place in order for a successful collaboration to occur. It is hard to overemphasize exactly how important these factors are. In fact, these are all factors that do not materialize instantly. They require much thought and commitment and must be shared among all of the collaborators.

The Educational Purpose or Goal

Before considering if online collaboration in some form might help meet your needs, you should closely examine your educational goal. What are you hoping to achieve? What would success look like? What are some concrete outcomes that you hope to see? As you consider your educational goal and the possibility of using online collaboration as a means to achieve this goal, you should also consider the alternatives. What could you achieve in person? What are the rewards and limitations of working together in-person or online? And because any type of collaboration, in-person or online, can be time-intensive, what is the hidden cost? In other words, what will you not be able to do if you are dedicating time and resources to a collaborative project or program?

As you cast a critical eye on your educational goal, we encourage you to also examine how online collaboration could support, improve, expand or deepen the educational encounter in some way. Could people be involved who otherwise wouldn’t be able to contribute face-to-face? Are there aspects of working together online that provide distinct advantages to the in-person work? Although the cost in terms of time can be considerable, also consider how your program or project could benefit over the longer term.

Remember, any collaborative project should clearly define a shared goal and purpose at the very beginning of the collaboration, with a genuine understanding of shared responsibility, mutual authority and accountability for success, along with sharing of resources, risks, and rewards. By setting goals, planning and prioritizing, the collaborators should make agreements about the what, who, when, where, why and how of the project. Each member of the team should also understand both the big picture and individual responsibilities.

A Desire to Innovate, to Create Something New

It is true that innovative solutions and ideas can come from individual insights and breakthroughs. But by working together and embracing the unknown, we can take risks, test, implement and evaluate our ideas. When people influence others to collaborate in mutually beneficial ways, it often creates a place where innovation can thrive.

Time

In many instances, we tend to forget how much time is needed to complete a project. It is often hard to quantify via a fixed arrangement, such as two hours per week when first embarking on an online collaborative learning endeavor. We have found that any given collaborative project can take at least a year to develop before involving the public. As with many programs, in the early planning stages, it might take only a few hours a month to begin to develop a program or project, but it could easily take 10 hours or more per week as the program intensifies.

Mutual Respect and Trust

In many cases, a collaborative project is seen as an experiment, to begin with, and we need to understand that there is no existing path or formula to follow. We need to support each other, celebrate our successes and respect each others’ expertise and contributions, rather than focusing solely on our own tasks and responsibilities. Respect, trust, and confidence build over time.

Flexibility and a Positive Spirit

Innovation and creativity require quality time to think through options and opportunities. Flexibility is required for accommodating unexpected factors, challenges, and problems. When engaging in a collaborative effort, demonstrating a positive attitude will also serve as an essential component to the success of the project.

Open and Frequent Communication

The idea of open communication is not only to be clear about our intent, but also to follow through on what we say we will do. It includes soliciting feedback, encouraging others to play devil’s advocate and commending each other for proposing ideas that might be different.

A Willingness to Share in Tasks, Responsibilities, and Outcomes

A successful collaboration depends on everyone’s contribution. If participants do not contribute or share in a timely and regular way, then they could disrupt the progress of others. Working in different time zones and locations requires patience and persistence in returning and looking for responses. The very essence of collaboration rests on the premises of shared responsibility and collective accountability.

The Means

We will not devote a lot of attention to the tools themselves, as they change and evolve on an almost daily basis. However, it is important to consider the functionality of the various tools that are available the advantages of each type, the costs, and the skills and training that are needed for each collaborator to feel comfortable using them.

There are a number of categories of tools that you might consider when collaborating online. Here are a few:

Asynchronous Tools: Users may access these tools at any given time. Participants are not required to be online at the same time in order to engage in this Web-based activity. Participants contribute to the interaction on their own schedule, rather than at a specific time. An example of asynchronous interaction would be a threaded discussion.

Blogs: dynamic online publishing systems designed for two-way interaction by posting narratives and receiving responsive commentary. Examples: Blogger, WordPress, LiveJournal.

Wikis: online tools enabling users to add, remove, edit and change content remotely and collaboratively. Examples: pbwiki, Google Docs, Wikipedia.

Online Group and Social Networking: Web-based networking services that focus on building online communities of people who share interests and/or activities, or who want to explore the interests and activities of others. Examples: MySpace, Facebook, Yahoo Groups, Twitter, Ning.

Online Media Aggregating and Sharing: a website where users can upload, view and share different types of digital files such as videos, music, PowerPoint presentations, photos, etc. Examples: YouTube, Slide Share, Flickr, iTunes, Voicethread.

Course Management System (CMS): a collection of software tools providing an online environment for course interactions; these typically include a variety of online tools and environments, such as digital drop boxes for posting learning materials, a grade book, integrated email tool, chat room, threaded discussion board, wiki, etc. Examples: Moodle, Angel Learning, Epsilen, BlackboardjWebCT, Sakai.

Synchronous Tools: These tools allow participants to meet online on a given date and time to communicate and exchange ideas over the Internet, interacting with one another in real time.

Webinar Software or Services: a Web-based conferencing tool used to conduct live, collaborative and interactive, real-time meetings or presentations via the Internet. Examples: Adobe Connect, Elluminate Live, Microsoft Live, WebEx, Skype, GoToMeeting, Wimba.

Chat (online): a type of synchronous text messaging that instantly exchanges messages through an application via the Internet. Examples: Instant Message, Skype, Yahoo Chat.

Emerging Tools: “2010 Horizon Report: Museum Edition” from the New Media Consortium states, “Increasingly, museum visitors (and staff) expect to be able to work, learn, study, and connect with their social networks in all places and at all times using whichever device they choose. Wireless network access, mobile networks, and personal portable networks have made it easy to remain connected almost anywhere.” With that, there are many potential applications on the horizon that might be integrated into online collaborative learning.

Mobile Media and Location-based Services: a collection of software tools providing additional resources for reaching visitors and connecting the experiences that happen inside museums with those that happen outside. These include: cell phone tours, mobile apps, and ARG (alternate or augmented reality game connecting virtual and real experiences), or using QR code, a two-dimensional matrix barcode readable by QR scanners using a smartphone with a camera; encoded information can be text, URL or other data.

Creating a climate where online collaborative learning can flourish is not easy. Besides the tools and key ingredients listed above, online collaborative learning requires patience and persistence. But with the support of colleagues and the institution, and with a sense of adventure, online collaboration can be a new way to interact with and learn from others.