This article originally appeared in the March/April 2012 edition of the Museum magazine.

An excerpt from The Quality Instinct

“Please don’t get your hopes up. He’s a very difficult man.”

My heart sank. Instead of meeting America’s greatest expert in Greek art, it sounded like I was about to spend the summer shuffling papers. It was 1977 and i was one of 12 students who had beaten the odds to be admitted to The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s prestigious internship program. I was hoping to interview for a placement in the Department of Greek and Roman Art. Liz Childs, the head of the program, sat before the phone in her windowless office to schedule an appointment three floors up with Dr. Dietrich von Bothmer, the formidable chairman of the department.

“Are you going to call him anyway?” I asked, as she hesitated.

“Yes.” She paused. I couldn’t tell if she was deliberate or worried. “It’s just that Dr. von Bothmer doesn’t usually accept students from this program.”

Having been rejected by the Met’s program the year before as a junior at Dartmouth College, I had just graduated and was on my way to grad school in the fall, determined to have a career in museums. I had come to Met to learn effort and my career was apparently predisposed to reject me. After a brief phone call with no indication of what was being said on the other end, she hung up and looked at me in apparent wonderment.

“He’ll see you tomorrow.”

All day I kept replaying that one side of the phone call in my head to guess Bothmer’s frame of mind. The next morning, back at the Met, I mounted the stairs to the Greek and Roman Department offices in the museum’s attic. The gray linoleum tile, the narrow, claustrophobic corridor, the odors from the Fountain Restaurant below all seemed out of place in this bastion of precious things.

The energetic department secretary, Mrs. Springer, greeted me at the top of the stairs and told me to walk one door down the hall.

“You’re early,” she said. I was suddenly nervous. A year and a half of anticipation was now over.

Arriving at the threshold of this legendary office, I felt like I was watching a movie with me in it.

“Come in, come in,” barked the chairman in a Prussian accent, with evident impatience.

I scanned the surroundings. A modestly sized, low-ceilinged space with a skylight was lined with books, file cabinets and crammed document boxes. Two massive tables pushed together in the center of the office left little room to navigate. Placed on them was a selection of antiquities: a terracotta statuette, a drinking cup and some fragments of pottery.

“And what do you want?” he asked, as if my arrival was unanticipated. I answered that I was hoping for a placement in the department as an intern. He barely seemed to listen to my response, instead directing me to sit down as he lit a pipe.

“I read your honors thesis,” he began. “Highly speculative. I trust you’ll never do anything like it again.”

These words are still etched in my memory. I had toiled for months at my 90-page undergraduate thesis on the origins of pictorial space in Attic black-figure vase painting. My college advisor had been altogether enthusiastic about the results. And with not one or two but three Ph.D.s, Professor Matthew Wieneke seemed credentialed to make that judgment. But here I was, seated before the world’s leading expert in Greek vase painting, and my first instructions were to forget everything I had written.

“No, I won’t,” I answered unthinkingly. My pride was wounded, my curiosity aroused (what did he mean?), but self-preservation dictated that I follow his brisk lead. It was getting warmer. Light pouring in from the skylight above wasn’t the reason.

“What is she wearing?” he asked abruptly, pointing at a draped statuette in front of me.

So this was to be a test. Tests are rarely my finest hour.

The fragmentary figure of a woman was in baked clay, about 18 inches high, and headless. I thought it to be Etruscan or Italic but had never seen anything similar that wasn’t close to life-size. Open at the arms, the drapery hung heavily from the shoulders. It looked like a fluted column but one contoured to the curving forms of a woman.

“It’s not a peplos, is it?” I asked, feeling any confidence I brought into the interview slipping away fast.

“Yes, it is. You got that one wrong.”

I couldn’t tell if he was joking but on the whole, it seemed better to assume otherwise. My double negative had revealed my unease. He was quick to exploit it. I resolved to toughen up for what I assumed was the next round.

“Date it,” he said gruffly, gesturing at a Greek drinking cup.

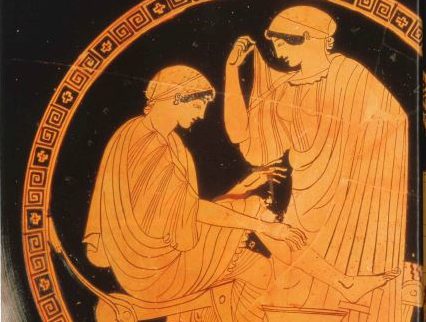

I had this one nailed. Despite his disparagement of my collegiate scholarship on vase-painting, the vessel had a familiar lively scene painted in the red-figure technique, encircling the exterior wall of a nearly foot-wide stemmed cup with handles on either side.

A banquet was portrayed in a continuous frieze interrupted only by the handles, with revelers reclining on couches and drinking from cups very much like the one on which they were painted.

“About 470 B.C.,” I ventured.

“Entirely wrong: 480 B.C.,” he said, leaving my head spinning. I wanted to protest. What difference can 10 years make? But eminent scholars like Bothmer take a missing decade seriously, even if a vase was 2,500 years old. This was his entire life, after all. I now wondered if it could ever be mine.

As the exchange came to an end, I realized it wouldn’t be. His standards were impossibly high, and my limited training had left me with little choice but to slink off to the Education Department in search of another placement. My brain was underwater. I can’t recall the rest of the truncated interview. I was awakened from a reverie of self-doubt when he ended our time together with these unforgettable words:

“Mrs. Springer will show you your office. I will see you Monday at 8:30 a.m.”

I stammered some kind of thanks and made my way out. I would have the same office from that summer in 1977 until I left the Met in 1987.

I regard that decade as the time when I acquired visual literacy. It was the beginning of my career and set me on a quest to learn how to discern quality in art-how to become what was known then, less disparagingly than today, a connoisseur. As I developed from an intern to an apprentice to a visiting professor at Princeton, I began to learn how to see, slowly acquiring the tools to recognize the gradations of achievement in art.

I began to learn how to see, slowly acquiring the tools to recognize the gradations of acheivement in art.

Lessons From Forgeries

Arriving at quick but informed judgments about artworks has always given me a surge of pleasure. Yet the process, like learning to hit an overhead smash in tennis, was halting, with plenty of trial and error. During that first summer with Bothmer, I was overwhelmed by stimuli, in large part because I was in constant proximity to masterworks. I had little to compare with the best. When you don’t know mediocre, you can’t fully judge what is great. It didn’t help that Dr. von Bothmer was a grudging teacher. At times I felt like I was a huge disappointment to him, and at times he took on a more avuncular manner. He would constantly quiz me when new works were brought in for inspection or purchase.

One day I was in the front office with Mrs. Springer when the phone rang. It was the jovial Bob Bethea at the information desk in the Great Hall. Bothmer came striding in.

“Who is it, then?” he barked.

“The Information Desk. A lady has brought in a Greek vase and would like someone to look at it.”

“Send her up,” he ordered.

This was a startling development. A few days earlier, when someone had called to ask about our coin collection, he had told Mrs. Springer without missing a beat, “Just hang up on him.”

Within a few minutes, the lady with her vase had climbed the stairs and faced the three of us, lined up along the office-length table as the sun beat down from the skylight. From a large shopping bag, she carefully withdrew a hatbox-sized parcel wrapped in brown paper and tied with string.

“Just put it down,” Bothmer commanded brusquely. “Is it wrapped only in tissue?”

She nodded but looked bewildered.

“Don’t you want me to open it?” she asked, unaware of the peculiar social conventions in our airless scholarly retreat.

Bothmer picked up the unwrapped package for an instant, then just as quickly set it down on the table.

“It’s a fake,” he pronounced.

“But you didn’t even open it,” sputtered our visitor.

“I don’t have to. Mrs. Springer, make out a package pass for the lady.”

As our visitor began to protest this apparent miscarriage of justice, he interrupted her with a hearty “Goodbye, goodbye,” then turned on his heel and padded back to his lair. I was left with the stupefied woman and her parcel. After shrugging my shoulders empathetically, and muttering an encouraging phrase or two, I made my way out too, musing on what was apparently a frequent parlor trick for Dr. von Bothmer.

It turned out that he had to be right. Like a wine connoisseur telling you the year, the grape, the vineyard and the hillside the grapes grew on, Bothmer could spot a fake instantly. This one betrayed its origins by being too heavy. Forgers of Greek archaic and classical vases have never mastered the light touch of sixth- and fifth-century potters. To this day, my first impulse is to heft a would-be antiquity.

Getting To Know Artists After They’re Dead

There were dozens of other such encounters over that decade, some more instructive than others. I’ll never forget when another visitor accompanied a vase-this one genuine-that she had purchased. She was already acquainted with Dr. von Bothmer, and they had the following exchange.

“I don’t know,” she said. “It’s just that the figures aren’t very vigorous.”

“Vigorous?” He chortled in mock amazement. “Of course not! This is by Douris. He painted delicate love scenes. If you want vigor, go find a battle by Makran!”

For Dr. von Bothmer, these usually unsigned masterworks were not simply objects. They were the living embodiment of artists’ personalities. He lived in their heads and was completely fluent in their visual language. He was even able to identify disparate fragments from six different collections as parts of a single vase-all from his encyclopedic memory.

I suspect a lot of us want to develop that depth of understanding in any endeavor we truly care about. To live vicariously in the imagination of those who have created the contents and settings of the best art the world has to offer seemed to me a wondrous talent. I wanted to have Bothmer’s antennae. I wanted and still want to have such fluid connectivity to artworks that the personalities, quirks, tastes, idiosyncrasies of these distant masters would be as familiar to me as the moods of my wife, son, and daughter. Just as I can see in my children resemblances to relatives and forebears that are invisible to strangers, I wanted to have that intense power of observation with art, too.

But before we can think about developing such acute antennae, it is best to know something about how art objects originally functioned and what they meant to their makers. This is part of acquiring a refined visual sense that is essential to connoisseurship. We can begin, for example, by learning to decode humble product design, or perhaps deciphering the colorful medals and ribbons on a soldier’s chest. There are symbols and metaphors that we can learn to see and under stand, and they can tell us why something was created.

A Faculty Brat’s Advantages

Much of what I have learned about seeing has been subliminal, prompted by a privileged childhood. I use “privileged” loosely and advisedly. My family wasn’t wealthy. My privilege, such as it was, took the form of (a) access to creative people, and (b) travel abroad. During most of my school years, I grew up in a rent-controlled, university-owned apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. It was filled with some 7,000 books and the aroma of pipe smoke. At home, the primary currency was “the life of the mind.” My dad was a professor of English literature at Columbia University, and my mom was an advertising executive. We were middle class, but my classmates at school were, for the most part, the children of the super-wealthy in Manhattan. Dinner conversation in our apartment was more likely to center on debates about the Cold War, or fine distinctions of literary theory, or the pertinence of the 18th- and 19th- century authors to our time-which helps explain why my brother Brom went on to become a scholar of Immanuel Kant.

I, however, was ill-suited to the metaphysical. I preferred concrete expressions of human potential. I liked objects. In shorts and knee socks in 1966, I collected a bottle of water from the Roman Baths in Bath, England, imagining that this was the very same water used by the ancients. (I still have the water.) I marched through fortresses in southwestern France pretending to be a knight preparing for battle. I stood in St. Peter’s, ogling the bounty of the Crusades, noting that these marvels were unavailable back home on the concrete island of Manhattan except behind glass at the Metropolitan.

My Grandfather’s Magical House

My grandfather was the playwright Maxwell Anderson. In the 1920s he acquired a couple of dozen acres along South Mountain Road near New City, N.Y., ultimately dividing these up in equivalent parcels for his three sons, my father being the eldest.

We spent the summers when I was young in a prefab house that my parents bought from the ninth floor of Macy’s department store. When we were little, my brother and I used an outhouse a few dozen steps from the front door, until my parents finally got around to adding a working toilet in our little house. My dad, it seemed to me, got the short end of the stick because we lived in the city during the school year, while his two brothers had proper year-round homes there in the countryside. Born in North Dakota in 1912, he was a cerebral literary expert in the company of New York’s leading intellectuals during the week, and on weekends a mountain man inculcating his sons in the laws of nature.

In this enclave I spent childhood summers and weekends, surrounded by a fascinating crop of neighbors. A few houses down from us lived the composer Kurt Weill and his actress wife Lotte Lenya. Another actor, Burgess Meredith, was close by, as was John Houseman. The sculptor Hugo Robus, the painters Morris Kantor, Martha Ryther, Annie Poor and her husband the ceramist and painter Henry Varnum Poor. They all moved there when my grandfather did, in 1921 and 1922. It was a renowned artists’ colony. Musicians, artists, actors and writers, the people around us were all creative souls and ran the gamut from insightful to eccentric.

The most important neighbor to me was the artisan Carroll French, who made many of the fine pieces of furniture in our homes.

As a boy, I took for granted the exquisite artisanal surroundings in my grandfather’s house in Rockland County, where my ad exec uncle Alan and his wife Nancy lived. Everything was handcrafted-from the original music scores, to the fireplace andirons, to the tile work, to the hardwood railings. Unbeknownst to me, I was acquiring antennae about quality, with little or no effort at my end, and my greatest influence was Carroll French. Asked to enlarge my grandfather’s 19-century farmhouse to accommodate a family of five, French took it upon himself to carve the existing beams in the ceiling as if they were living creatures.

French’s imaginative marks begin outside the house. To start with, you enter through a carved Dutch door that today opens to a sweeping lawn. The Dutch door-really two separately hinged doors, one on top of the other, that swing independently-was invented to keep children in and pigs out while allowing light and air to bathe the interior. It was the most solid door one could conceive of, made of Philippine mahogany and other hardwoods. The door’s dovetailing was highlighted by carvings of doves, and incised on the inside was the Latin expression Exeunt omnes-a fancy way of saying “This Way Out.”

Once entering through the front door, you encounter a wide chestnut stair on the right, with no banister. It leads to the upper floor, where French fashioned an open balcony railing supported by a series of upright spindles, each animated by a different plant or animal. He topped off the stairs with a huge carved chestnut leaf, inviting a caress on the way up or down, that is folded over and grows up from. a modestly sized chestnut tree emanating from the floor. Other animals disport themselves upstairs-deer, rabbits, squirrels, red foxes, and turtles, all of which could be found live just outside the door. My childhood imagination took them in as if they were from the pages of a fairy tale.

The ceiling beams on the entrance floor were awash with water nymphs and other mythical creatures, perhaps as French’s sly nod to the waterfall and pond within earshot of the house. The original beam over the living room fireplace was longer than needed, so French carved the excess end of it in a spray of chestnut leaves projecting eastward into the room. The beam from the fireplace south to the dining area was also too long, so French carved the excess, which, it should be noted, hung over a hand-carved sideboard, with a roast pig, its mouth open to hold an apple. These accents were magical to my young eyes, and I never tired of gazing at these quirky features. They all hung together to create a personality for the house itself-playful but sophisticated, suited to the surrounding countryside, and slightly wild. They reflected my worldly, rustic, free-range grandfather perfectly.

A Humble Table Tells A Tale

In my parents’ Manhattan apartment was, among other pieces, French’s oak side table inscribed “for MA 1934 by CF.” The inscription instilled in me the naive assumption that everyone was entitled to personalized furniture. After all, it was just carved wood, and therefore affordable.

As I compose this on the wooden writing table Carroll French carved for my grandmother, its fine craftsmanship prompts a flood of visual associations- and also the childhood memory of seeing it not as a table but as a masterwork. Made of cherry wood, it is modestly proportioned, about 5 feet long and only 3 feet deep. Around the front and sides are low-relief carvings, one including a mouse reading a book with the title “You Who,” an inside joke on You Who Have Dreams, a book of my grandfather’s poetry published in 1925. Along with other less bookish mice, leafy plants grow up the length of the table legs.

My eye never tires drinking in the details of the table, and family memories are only part of the reward. Running my fingers across the bas-relief, I can imagine the original blows with mallet and chisel that transformed the unfinished surface into an imaginative playground.

As an antique, it bears the subtle markings and distress of an object that has endured the touch of three owners. Each bruise carries an echo of lives lived. But the relief carvings are so vital and playful that they stand in as a kind of perpetual conversation between the maker and the original owner. As a witness to this conversation, it matters less to me that the table is in my possession than that I can eavesdrop at any time. That has been my great privilege: I knew the man who made it.