This article originally appeared in the March/April 2012 edition of the Museum magazine.

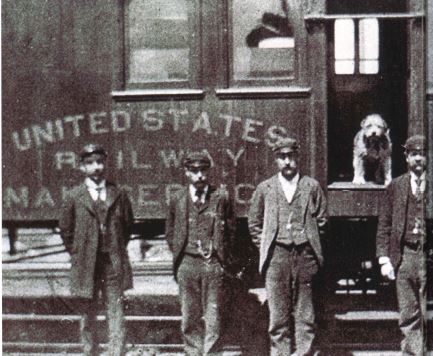

Everyone can relate to a dog. That was the philosophy underlying the National Postal Museum’s campaign on Owney the Postal Dog, the mangy mutt that traveled the country with the Railway Mail Service in the late 1800s and whose preserved body was given to the Smithsonian in 1911. Last year the Washington, D.C., museum endowed Owney with a voice on social media, brought him to life via an interactive iPhone app and e-book, and engaged audiences through an exhibition, public programs, and an online Owney look-alike contest.

The goal was to reach people on an intimate level. “We knew he had a story that people automatically loved,” explains MJ Meredith, museum technician. “We thought if we were able to get that story out to a wider audience, we would create a deeper, more widespread connection to our museum.”

Between shelving units, specimen cabinets and HVAC systems-just a few of the often-pricey implements for preserving objects-collections can seem like costly commodities. Instead, they should be viewed as a key outreach tool, advises Larry Reger, president of Heritage Preservation. “The idea of having to properly store and display collections is very often viewed as a drain on resources, when in fact it can be a tool for learning, for bringing in new audiences and for raising money,” he says.

There are myriad ways to go about this, five of which are explored here. But the fundamental goal is to make personal connections between the collections and the community, bridging the museum-visitor divide by providing opportunities for people to get involved and feel invested.

1.Mascots

The Postal Museum started small with Owney-1.56 by .98 inches, to be exact. That’s the size of the Owney the Postal Dog Forever stamp, which was issued in July 2011. When staff found out about the stamp’s forthcoming release, they decided to make it a splash.

Along with a four-day festival, the launch involved an Owney look-alike contest on Facebook. Staff emphasized that, more than a physical resemblance, the winning dog would embody the “Owney spirit”friendly, adventurous and filled with wanderlust. At stake was an Apple iPad 2, plus an Owney e-book, plush toy, signed book and a sheet of his stamps. In addition, the winning dogs’ photos would be displayed in the museum for two weeks.

The contest “took on a life of its own,” Meredith recalls. The media caught wind of it and began to spread the word. Contestants went beyond the paragraph and photograph they were required to provide to enter, creating blogs and posters to advocate for their canine candidate. Surprisingly to staff, applicants were more interested in their pup’s 15 minutes of fame than a $499 tablet. “It turned out no one cared about the iPad-all they wanted was their dog’s photo in the Smithsonian next to Owney,” says Meredith.

Owney is now among a group of animals representing museums, including Sue the T. Rex at Chicago’s Field Museum and Mr. Blobby the Blobfish at the Australian Museum. Both of these fearsome (or at least unattractive) creatures have devoted followings on Facebook and Twitter. Owney’s is vibrant as well: He had more than 1,200 fans and 1,000 followers as of December 2011. Facebook fans interact with Owney as though it’s perfectly normal to have an online

discourse with a 125-year-old taxidermic dog. “People respond to him on social media in a different way” than they do when viewing his exhibit in the museum, notes Meredith. “The museum can be seen as institutional, but Owney they say hi to him, talk to him. It’s interesting, the different levels of engagement we have through the same content but a different vehicle.”

Museums interested in identifying their own mascot should look to their strengths. Owney was much adored before the Postal Museum’s campaign began. “We realized that our visitors loved him, that people were writing books about him,” says Meredith. “I always say look to the stories in your museum. What’s something people already love, that’s already popular, that people already have a connection to?”

Telling compelling stories is key to bringing a collection to life, according to Colleen Dilenschneider, who explores museums’ community engagement practices via social media in her blog, Know Your Own Bone. “The kind of impact that museums have lies in people who are inspired to visit because they are interested in the content because they are compelled to visit the collection behind a story that they’ve heard,” she says.

2. Adopt an Artifact

If visitors aren’t satisfied with an online chat with a favorite museum object, consider allowing them to adopt one. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Philadelphia, known as the Penn Museum, started its Adoptan- Artifact program in 2009. The objective was to make people more aware of the importance of the collections, says Amanda Mitchell-Boyask, director of development. Adopters receive a photograph and information sheet on their chosen object “so they will know more about it and have more of a connection to it”, she explains.

The museum selects 10 or 11 objects each year to put up for adoption. As with finding a mascot, the choices should be based on what’s already popular, suggests Bea Jarocha-Ernst, administrative assistant in membership, who worked with Mitchell-Boyask in developing the program. To determine the first round of objects, they polled staff, had children at the museum’s summer camp vote on their favorites and looked at which postcards sold the best in the shop. Iconic objects are the most popular, Jarocha-Ernst says, such as the museum’s giant granite sphinx, which is considered its signature object.

The program has a range of adoption packages. Chip in the minimum of $35 to receive just the aforementioned certificate, photo, and description. Go above $400 to also enjoy complimentary admission passes, an invitation to Adopt-an-Artifact Day and a private talk with the museum’s conservator.

It’s $2,500 to adopt a carousel animal at the Shelburne Museum in Vermont, but the hefty price tag pays both for conservation of the objects and for a unique educational experience. With their contribution, donors fund bringing students from art conservation graduate programs to the museum to work on the adopted animals, under the direction of Nancie Ravenel, objects conservator. She has supervised 17 interns, who came from Canada, Switzerland, Taiwan, Bhutan and elsewhere in the United States to conserve the carousel. Donors are kept informed and involved and involved in the conservation process. After choosing a name for their sponsored animal, they’re kept apprised

of its progress and are invited to visit the conservation laboratory and meet the students they support. When the project is complete, a plaque is installed to thank the donors for their contribution.

Integral to adopt-an-artifact programs is finding objects that have particular meaning to potential donors, says Ravenel. “In one case we had a person adopt a carousel animal for her husband, who had ridden that carousel as a child,” she recalls. In another case, a couple named their horse after their grandson so he would feel connected to the museum as well. “It’s pretty wonderful to hear from these people why they’re adopting the animal, their connection to that object.”

3. Volunteers

It’s easy for community members to connect with collections if they’re working with them hands-on. Having volunteers in the collections can not only ease staff’s workload, but can also serve to bolster interest in the museum.

Jackie Hoff began volunteering at the Science Museum of Minnesota in 1995· Today, as director of collections services, she manages a number of the museum’s nearly 1,400 volunteers. Ranging from high school students to retirees, this group is essential to the museum’s operations. “We’ve been around for 104 years now, and I can’t imagine this museum functioning without volunteers. It would be just impossible,” says Hoff.

Susie Fishman-Armstrong, laboratory coordinator at the Antonio J. Waring, Jr. Archaeological Laboratory, has a similar reliance on volunteers, though on a smaller scale. She is the only full-time employee at the laboratory, which is part of the University of West Georgia in Carrollton, with three staff members who can each work only eight hours per week. “I have collections that just come in and sit there until I get a volunteer,” she admits. “I’m barely able to manage incoming collections, and without volunteers, I would never be able to grandfather in any of the older collections and maintain inventories.”

But beyond providing an extra set of hands, a volunteer can become a powerful advocate. Part of the laboratory’s mission is to educate the public on the importance of protecting archaeological sites. On their own accord, volunteers have helped the lab meet this objective. “Volunteers who have come through here have joined local societies and have worked with them, taken what they’ve learned here into teaching others,” says Fishman- Armstrong.

By spending time in the collections, volunteers gain an understanding of the amount of work and research that goes into caring for the objects, says Hoff. They then share this understanding with others the old-fashioned way. “We heavily promote social media and every other form of knowledge, but the best thing still is word of mouth,” she attests. “Having passionate volunteers who care about what you do and how you do it is huge.”

4. Community Curators

Museums can also draw on visitors’ connections to objects by allowing them to select one for exhibition. Following the lead of such exhibitions as “Click! A Crowd-Curated Exhibition” at the Brooklyn Museum and “50/50: Audience and Experts Curate the Collection” at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, “Crowdsourcing a Collection” opened at Massachusetts’ Concord Museum last fall, in honor of the museum’s 125th anniversary.

The impetus for Concord’s crowdsourcing was to engage and collaborate with local, regional and national audiences. “It felt like a really interesting opportunity for us to reach out into the community,” explains Executive Director Peggy Burke. “Rather than doing a top-down exhibition for our 125th anniversary, [we wanted] to really let go of that and ask other people how they regarded this pretty amazing collection.”

Author, historian, and Concord resident Doris Kearns Goodwin signed on as the honorary curator. Thirty individuals and 10 sister institutions were invited to serve as guest curators. Each was sent a CD containing images of 100 objects from museum’s collection and asked to pick one that felt significant in some way. Included on the mailing list were author Robert Cole; Yasukazu Nakamiya, mayor of Nanae, Japan, Concord’s sister city; Senator John Kerry; and Concord Honored Citizens Marian Thornton and Dot Higgins. The exhibition also features objects associated with past Concord residents, such as Louisa May Alcott and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

The process of choosing works “led to some personal connections between members of the community and the museum in ways that were really moving,” says Burke. Kerry wrote that he selected an image of transcendental feminist writer Margaret Fuller because of his work advocating women’s rights in Congress, as well as his pride in his wife and two daughters. Marian Wheeler, described on the wall label as a “contented grandmother of eight grandchildren and great-grandmother of 16,” chose a 19th-century mahogany cradle that served as a model for the one her husband designed for their first child.

In the exhibition, which is open through March 18, visitors are encouraged to “add their voice to the crowd” by posting stories about why certain objects speak to them. The responses have been “very personal, which is what we were going for,” reports Director of Education Susan Foster. For example, a centennial plate from 1875 resounded with several visitors who started college in Concord 100 years later.

Two of the guest curators, both local residents, chose as their object a display of pencils made by Concord artisan William Monroe around 1840. Henry ]. Dane remembered the pleasure of manually sharpening pencils as a boy; Rosita Corey explained that Monroe had fashioned the pencils in the house she’s lived in for 75 years. Several visitors have posted stories about why they, too, are drawn to the pencils-because they love to sketch or write, or because they savor the idea of using a writing utensil to take notes rather than a computer. Their input provides new perspective to the exhibition, Foster notes. “It really elevates it and connects people who don’t even know each other across communities.”

5. Behind the Scenes

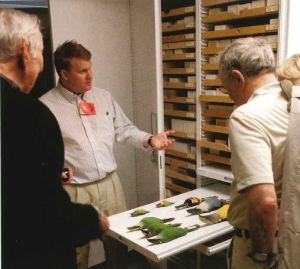

Now that the community has played curator, why not offer an even closer look at the museum’s inner workings? Behind the Scenes Night is one of the most popular benefits of membership at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle. Held once a year, the evening is an exclusive opportunity for members to meet with curators and collections managers, who show off objects from their particular specialties and discuss current research.

While behind-the-scenes tours are offered to nonmembers at other times, “this is the only night when all of the staff is standing in the collections and has pulled out some of the most meaningful or wacky or crazy aspects of the collection,” says Julie Stein, executive director. The curators and collections managers display maps, graphs, sketches, photographs and other related materials to give an in-depth look at their objects. “Not only do you get the magic of seeing behind the curtains, like in The Wizard of Oz, but behind that curtain is unbelievably more than you’d see on any other day or night,” Stein adds.

Going behind the scenes is appealing to visitors because they enter a place few others get to see, Stein says. Offering behind-the-scenes tours is appealing to museums, on the other hand, because it makes them more approachable. “I think it is a way to engage the community that helps demystify the world of museums,” she says. “In the day and age of transparency and community .. value, it is important that museums demystify the institution.”

Jeff Tenuth, science and technology collection manager, has been giving behind-the-scenes tours at the Indiana State Museum for 25 years. A typical tour of the museum’s natural history collections starts on the dock, where most items come in after excavation. The next stop is the wet lab, where objects are cleaned, followed by the prep lab, where other objects receive chemical treatments. The tour continues to follow the process until reaching the objects’ final landing place in the storage rooms.

The idea is to encourage viewers to think about collection items, Tenuth says. “When visitors come into a museum, what they see is the end product. They see a gallery. And for the most part they don’t think about how everything got to that point. By showing them the collection itself and talking to them about the mission of the museum and why we collect what we collect, we give them a much broader perspective of what the collection needs.”

Tenuth says he’s never had anyone walk away from a behind-the-scenes tour disappointed. “They’re always astonished, surprised and pleased because they say, ‘Geez, I had no idea.’ That’s why I have done it this way for these 25 years,” he explains. “If I can get the public to know just a little bit more about what we do behind the scenes, it’ll make us more friends, more supporters and more donors.”

As with the other methods, behind-the-scenes tours are designed to get visitors involved and invested in the museum-in short, to make them care. “The more they see and more they learn, the more interested they are and the more value they see to the community of the collection,” says Tenuth.

Joelle Seligson is associate editor, Freer and Sadder Galleries, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., and former associate editor at AAM.