This article originally appeared in the January/February 2013 edition of the Museum magazine.

Excerpt, From The Holy Land to Grace/and: Sacred People, Places and Things in Our Lives, The AAM Press, 2012.

What makes Graceland unique among both religious and secular loca sancta—a Category 5 hurricane, a 9.5 earthquake on the Richter Scale—is the fact that nearly all the defining characteristics of a holy place, whether ancient or modern, whether religious or secular, are concentrated there. Even the Church of the Holy Sepulchre cannot match that. Not only was this Elvis ‘s home for the last 20 years of his life, it was the site of his death and funeral, and it is the location of his body. Graceland is itself a relic and is filled with relics, some of which were on site when Elvis died and some of which have been returned over the years.

By contrast, John F. Kennedy was killed in Dallas and is entombed in Arlington, Va., far from his boyhood home in Massachusetts. The material remains of JFK’ s life are prized, commanding top prices at celebrity memorabilia auctions, but they are dispersed all over the world. Martin Luther King, Jr. was killed in Memphis, but his tomb is in Atlanta near his boyhood home and his church. Princess Diana’s death locus in Paris is difficult and dangerous to get to and very far from her tomb, which is set on an island in a small lake in England. Harvey Milk was killed in San Francisco’s City Hall, his apartment and photo business are in the Castro District of the city, and while there are relics there to commemorate his life and martyrdom, Milk was cremated and his ashes dispersed. The “Mexican Madonna” Selena’s 99 loca sancta, including her grave, her museum with her life-size statue as Mirador de la Flor and her Porsche, her parents’ home and the site of her murder at a Days Inn Motel are all in her hometown of Corpus Christi, Tex., but they are scattered around the city. Neverland, near Santa Barbara, is bereft of nearly everything related to Michael Jackson’s time there. Moreover, Michael Jackson died in a rented house in the Holmby Hills neighborhood of Los Angeles, was eulogized miles away at the Staples Center, and his body is now locked away and inaccessible in the Grand Mausoleum at Forest Lawn Cemetery in Glendale, which is far from both the death and funeral locations.

By contrast with Neverland, Graceland is and always has been a vast repository of Elvis relics. It gathers in one place all the everyday items associated with Elvis that parallel the everyday items from the life of Jesus that the Piacenza pilgrim (c. 570 A.D.) encountered at various locations in the Holy Land, including Jesus’s holy cradle and swaddling cloth in Bethlehem and his childhood schoolbook in Nazareth. Graceland is not only the fully furnished Elvis house, it is the Elvis tomb and, though off-limits to visitors, the place of Elvis martyrdom, in the form of the second-floor master bathroom, over the front door, which remains pretty much as it was the day Elvis died there. In the Trophy Building, between the Elvis house and the Meditation Garden with the Elvis tomb, visitors are invited to contemplate a cornucopia of dazzling Casual visitors may see Graceland through very different eyes. Many will form their opinion of the Mansion from the perspective of today-as a home fitting (or not) for the greatest entertainer of all time while others will judge it in relationship to the Presleys’ meager early life in Tupelo. The former group, even before seeing the Hall of Gold in the Trophy Building with its hundreds of gold and platinum records, will struggle to reconcile this modest house in this rundown neighborhood with the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll, forgetting that Elvis bought Graceland when he was just 22 years old and chose to keep it as his home until the day he died.

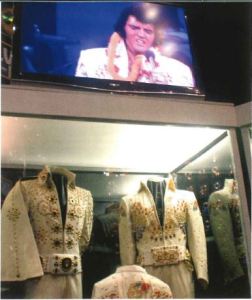

Elvis relics, mostly items of clothing: a gold lame suit and white bucks of the ’50s, various theatrical outfits from his movie years of the ’60s and, finally, a series, of increasingly elaborate caped and rhinestone-studded jumpsuits from the touring and Vegas concerts of the ’70s. Among these is the most striking relic of all: Elvis’s famous jumpsuit from the “Elvis-Aloha from Hawaii” concert of 1973, with its massive eagle-encrusted trophy belt. ><

Graceland will make much more sense—and have much greater impact—for the Tupelo group, especially after a visit to the Elvis Birthplace Complex. That 1939 Plymouth out back of Vernon’s shotgun shack, pointing toward Memphis and signaling, according to the inscribed granite block nearby, the Presley family’s 1948 departure in search of a better living, becomes a Cadillac just a decade later at Graceland. Similarly, that tiny wooden table in the birth house, just a few feet from the Presley pot belly stove, has become in Graceland Mansion a grand dining room table beneath a huge chandelier, adjacent to a large, modern kitchen. The family that slept together in a single bed in the front room in Tupelo would have the luxury at Graceland of multiple bedrooms, with the one for Elvis’s beloved mother Gladys on the ground floor larger than Vernon’s entire shotgun shack. And the list goes on, from Graceland’s white, gold and blue living room, to its music room just beyond with its stained glass peacocks and its (sometimes) gold piano, to its downstairs yellow and black den with its three vintage TVs (ABC, CBS and NBC, just like President Johnson), to its intensely cozy fabric-lined pool room with its tip-less pool cues and, finally, to its triumph-of-tacky Jungle Room upstairs. The transformation of Tupelo into Graceland is the transformation of America from the ’40s to the ’50s, with Elvis as its hero and Rock ‘n’ Roll as its enabling vehicle.><

Graceland pilgrims acknowledge group identity not only through their license plates but through their clothing, jewelry and tattoos.

The appearance of the Elvis grave shrine in mid-August and the quality and tempo of activity around it are very different from the non-holiday season. During Elvis Week, there will likely be more than 25,000 visitors to Graceland, and (me senses immediately that as a group they stand apart; these make up the most concentrated pool of Elvis pilgrims and these, disproportionately, account for Elvis pilgrimage activity. Characteristically, the August Graceland pilgrim travels a greater distance than the June Graceland tourist and expends greater effort; almost certainly this will not have been the first visit. Paradigmatic, though extreme, is Pete Ball, the EP-tattooed London laborer who between 1982 and 1987 came to Graceland 53 times, all the while never stopping anywhere else in the United States.

As a group, August pilgrims tend to be older than June tourists and they appear to be less affluent. These are the folks of America’s blue-collar, working-class cities, especially of the Old South. (A survey of the license plates in the various Graceland parking lots bears this out.) August Elvis pilgrims were poetically evoked on site by Selby Townsend on the Aug. 14, 1987 Nightline segment entitled “Remembering Elvis” as “those very special people” who:

… tease their hair, chew gum, swear, drink Pepsi Cola, smoke cigarettes, and dress too young for their years. They come here in Chevies and Fords… Most of them went to high school and some even finished. And they all know what it’s like to work for a living. We are the blue-collar workers, the fans, the believers in magic and fairytales. We’re not smart enough not to fall in love with someone we never met. We’re not rich enough to buy everything we want from the souvenir shops. We don’t even have sense enough to come in out of the rain. But Lord, we’ve got something special. Only one that feels it can understand it. We share the sweetness, the emptiness, the understanding. We’re the Elvis generation-wax fruit on our kitchen table, Brand X in our cabinet, a mortgage on our home, Maybelline on our eyes and love in our hearts that cannot be explained or rained out. He was one of us.

Nothing could be more unlike the anonymity and dispassion of tourist travel than the intense bonding that takes place among the faithful during Elvis Week. Anthropologists speak of the communitas (“commonness of feeling”) of pilgrimage and emphasize the liminoid (“threshold”) nature of the experience that, like a rite of passage, takes the pilgrim out of the flow of his or her day-to-day existence and leaves him or her in some measure transformed. Nowhere was community and bonding more apparent during the late ‘8os than at the Days Inn Motel on Brooks Road, between Graceland and the airport, the home of the Tribute Week Elvis Window Decorating Contest.

Communitas began in the parking lot with its rows of Lincolns and Cadillacs bearing Elvis vanity plates, and it continued around the pool, where pilgrims gathered to drink Budweiser and reminisce. One sensed in the poolside conversation of those days the inevitable evolution of recalled anecdote from, among the older fans, those stories relating to the living Elvis too, among the younger fans, those stories relating to extraordinary events surrounding postmortem August gatherings. This, too, must have had its counterpart in the early Christian world, as those pilgrims and locals with memories of the living saint died off; in the later 5th century, the distinction would have been between those who actually knew Saint Simeon the Stylite and those who knew only his empty column and his vita.

Although the texture of conversation then at the Days Inn was interwoven with accounts of the seemingly supernatural-the seeds of future Elvis miracles- its center of gravity was shifting toward stories of extraordinary pilgrimage, typically involving long distance and great sacrifice. There at poolside in 1989 was Betty Lou Watts, who had made the Baltimore Sun a year earlier for her extraordinary Elvis devotion and her collection of Elvis relics that included a pair of Elvis’s black silk pajamas she claimed never to have worn. Betty Lou cheerily told anyone within earshot at poolside that she had never missed an Elvis Week since its inception in 1978, but that this year had been different. It seems that Betty Lou’s son was at that very moment in a Baltimore hospital as the result of a bar fight having been, as they say in cities like Baltimore, hit “upside the head” with a 2 x 4· With no extra cash, Graceland in mid-August was out of the question, until some of Betty Lou’s local Elvis friends took up a collection and put her on the Greyhound Bus to Memphis. For those gathered at the Days Inn that year, Betty Lou Watts was offering the stuff of communitas: a gratifying Elvis story with a gratifying Elvis outcome, worthy of the compassion and philanthropy that was the hallmark of Elvis himself.

Twenty years later, in 2009, EP vanity-plate Cadillacs were replaced by EP vanity plate GMCs, African American Elvis pilgrims were still in very short supply, and the hub of Elvis Week communitas shifted from the window decorating contest, which became much smaller and at a Days Inn Motel just south of Graceland’s Automobile Museum, to the Elvis Week Entertainment Tent in Graceland Crossing. (The Days Inn of the ’80s has since gone into precipitous decline.) There, each day of Elvis Week, beginning at 12 noon is an open microphone with a full menu of EP backup music for aspiring Elvis tribute artists. Pilgrims stay for hours in and around the tent, making friends and swapping stories, just as in the past, and taking pictures of one another, against the musical backdrop of amateur Elvises whose singing skills range from the near sublime to the profoundly ridiculous. Budweiser is readily available from a nearby stand, and there are plenty of Elvises in attendance (and a few Priscillas, too) who are there not to sing but simply to be seen. Some among the Elvises could be the King’s contemporaries, and there are those at least as young as the little Tupelo Elvis. The first up on Aug. 13, 2009, was Danny Frazer, a paraplegic from birth. Despite his physical challenges, Danny gave a superb performance, but his impact on the fans was all the greater for having no legs, especially when he sang Walk a Mile in My Shoes, tapping out the rhythm with his right hand. Cheers and tears erupted throughout the tent, there was the ritual passing of sweat scarves to 70-somethings in the front row, and after 40 minutes, Danny Frazer was gone-though only after posing for photographs with a teen in a wheelchair. Like Betty Lou Watts 20 years earlier, Danny Frazer was creating Elvis Week communitas and, for some, a moment of liminality.

Much like Jerusalem pilgrims, Graceland pilgrims, whether at the Days Inn poolside in the late ’80s or in the Entertainment Tent two decades later, acknowledge group identity not only through their license plates but through their clothing, jewelry, and tattoos. There is first-name familiarity among the “we” and an openness to new members, who are initiated through friendly interrogation: “How many times have you been to Graceland?” “How many Elvis concerts did you attend?” Elvis’s motto in life was “Taking Care of Business,” and the unspoken motto among the postmortem “we” is “Taking Care of Elvis.” The despised “other” extends well beyond the old familiar circle of

Colonel Parker, Albert Goldman and Memphis Mafia turncoat Lamar (“Lardass”) Fike, who was Goldman’s main inside source, to include Geraldo and the media in general, which is universally viewed among the fans as having always treated Elvis, his family and his fans as southern hicks. Priscilla is in this evil mix as well, since her infidelity is believed by most to have destroyed Elvis’s will to live and because she is generally acknowledged as having been “uppity” and as having wrecked Graceland by redecorating it.

Gary Vikan served as director of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, from 1994-2012. From The Holy Land to Graceland: Sacred People, Places and Things in Our Lives is a publication of The AAM Press.