This article originally appeared in the January/February 2013 edition of the Museum magazine.

A History Museum Just For Kids

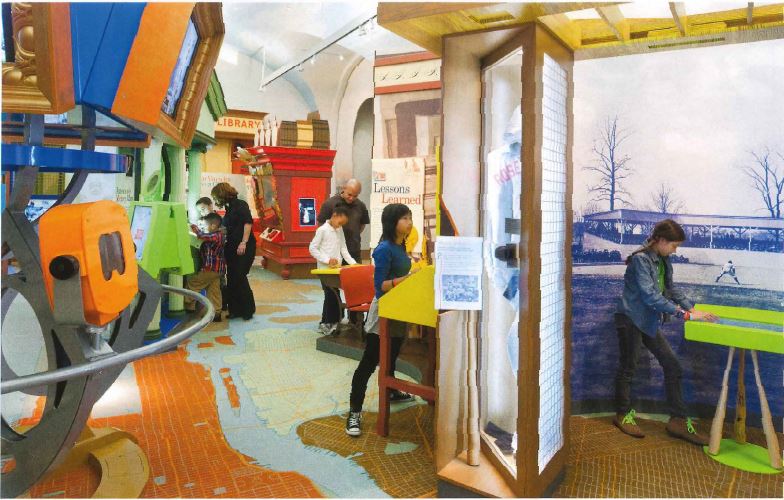

“This is awesome! You’ve gotta see this,” a fourth-grader squeals to her friend, pointing to the hologram-like image of Cornelia van Varick, an 11-year-old Dutch girl who lived in late 17th century Flatbush, now part of Brooklyn. The

media piece lets the students explore the contents of the home of Cornelia’s mother, textile merchant Margrieta van Varick, and chart the global trade routes she used.

Nearby, four boys spin cylinders printed with hall-of-fame baseball players’ faces, until they’ve selected a “dream team.” The interactive display sifts the players’ stats to determine how they might fare against the 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers. A scoreboard overhead quickly fills out, inning by inning, while one boy does an impromptu play-by-play. Their team beats the Dodgers and, with hands raised in triumph, the boys stampede to the next pavilion.

Nearby, four boys spin cylinders printed with hall-of-fame baseball players’ faces, until they’ve selected a “dream team.” The interactive display sifts the players’ stats to determine how they might fare against the 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers. A scoreboard overhead quickly fills out, inning by inning, while one boy does an impromptu play-by-play. Their team beats the Dodgers and, with hands raised in triumph, the boys stampede to the next pavilion.

Magnifying glasses swing from lanyards around children’s wrists as they pinball around a 4,000-square-foot space with a map of New York on the floor and a cloud-flecked painted sky on the vaulted ceiling. The energized 8-year-olds on a field trip from Grace Church School in Manhattan are “history detectives,” charged by a volunteer museum educator with investigating how children’s lives in earlier centuries differed from theirs.

These are some typical experiences at the DiMenna Children’s History Museum (DCHM}-a museum-within-a-museum opened by the New-York Historical Society (NYHS) last November. The new museum is part of a three-year renovation project that’s now complete at the society’s stately 1904 building on Central Park West. A $5 million donation from hedge fund manager Joseph DiMenna and his wife, Diana, contributed to the development of the children’s history museum.

When the society, proud of its standing as the oldest museum in New York, started planning the makeover of part of its lower level, it discovered that strictly speaking, there was no other children’s history museum in America. (Historic villages and parts of other historical societies’ and museums’ exhibit space offer plenty for children, NYHS officials acknowledge, but are not aimed exclusively at kids.)

The Society’s president, Louise Mirrer, feels that too often the study of history falls through the cracks in the New York City Public Schools. Writing for the Huffington Post, Mirrer cited the Nation’s Report Card, a 2010 National Assessment of Educational Progress issued by the U.S. Department of Education, which showed that fewer than one-quarter of the students tested were judged proficient in U.S. history. A sense that institutions like hers must step up drove the $70-million renovation that, as she wrote in her blog post, “changed our landmark building from a beautiful but enclosed treasure house into’ an open and welcoming showplace.” While designed to engage the entire public, the makeover included the DCHM as an effort to reach younger visitors—those Mirrer believes need it the most.

Certainly, few other museums have such a treasure trove to draw from. The historical society has 1.6 million objects,

paintings, documents and photographs in its collection. “The society is amazing in the wealth of objects and documents and photos we have. It’s huge,” says DCHM Director Alice Stevenson.

In conjunction with museum design firm Lee Skolnick Architecture + Design Partnership, work began on blending design elements with historical content. Valerie Paley, an NYHS staff historian, and curator of other new permanent post-renovation installations says she met with the museum’s director of education to “learn not only about the content of the history curriculum of our target group (fourth grade), but about what engages and excites this age group intellectually. We alighted upon the fact that kids are interested in what kids from the past did, placing some of the things contemporary children do today, like going to school, in a context they could relate to.”

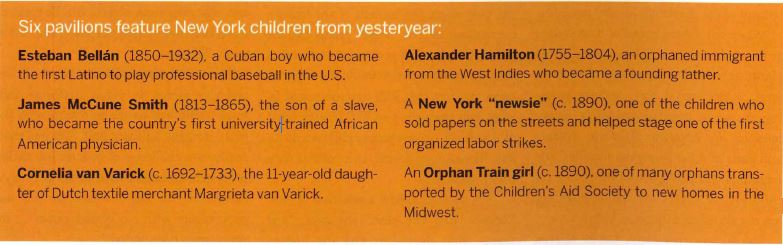

“We decided to find a selection of New Yorkers from the past,” she says, “and frame their narratives and the history contextualizing them from the perspective of a child.” Some of the six real-life New Yorkers whose lives and experiences would make up the museum’s six pavilions (see box, p. 40) had already been the subjects of temporary exhibitions in the larger museum.

“We [also] wanted to add other unrelated historical content to enrich the children’s museum experience,” Paley says. Thus the museum included the “New York Viewfinder” showing the same locations, then and now; George Washington’s inauguration in New York City and a related piece on civics and voting; and the “American Dreamer” pavilion that places young visitors in a historical context by juxtaposing their photographs with images of famous New Yorkers, past and present.

Displayed along “touch rails” are reproductions of historical items like a 19th-century baseball and early paper money that are less likely to be damaged by young hands. Other treasures-300-year-old silver beakers from the Dutch Reformed Church in Brooklyn; grooming items used by Gertrude Kellogg, a New York theater star in the 1800s; a sampler stitched in 1820 by a 15-year-old at the African Free School-are kept behind glass. Stevenson says that over time, objects will be rotated in and out, drawing on the main museum’s vast collection.

The society settled on a blend of interactive games on video platforms and more traditional hands-on objects with labels-roughly half and half. “We had that really core challenge of how do you make an objects-based museum hands-on?” says Stevenson. “So that’s where we saw an opportunity with our digital games . . . to represent a time period.”

“We could use photos and images and documents from our collection, and the designers did an amazing job of creating that environment within the game,” she explains. “We also felt really strongly that the digital touchscreens weren’t a way to just touch a screen and read another label. We really wanted gameplay to be at the core of what we did with the games and touch screens.”

Architect Lee Skolnick reveals a formula: “We call it an experiential matrix. Along one axis is all the different kinds of visitors you might have, from grandparents to little kids who can’t read to everything in between,” he says. “And the other side is modes of interaction and interpretation. What we try and do is match content to the various modes of interpretation-a simple hands-on or a much more complex game? Some stories have much more appeal to young girls, some have more appeal to older boys. So we know we’re delivering to everybody what they can absorb.”

Stevenson recognized, though, that a group of schoolchildren could spend an hour and a half just playing one of the games, like “Newsies,” in which a player becomes an 1890s-era child selling newspapers on the street. Players accumulate virtual nickels and dimes with which they make decisions such as whether to buy food or lodging. After a rough night of sleeping alfresco, a child’s video character moves more slowly while selling papers the next day. (Skolnick says it’s a fortuitous coincidence that the Tony Award-winning musical adaptation of the Walt Disney film Newsies opened on Broadway this past year.)

This is where the “history detectives” theme comes in. During an initial 15-minute free exploration of the museum, schoolchildren are asked to find one thing that was different about a child’s life in early New York. (“Kids had to work!” is a common discovery.) They’re brought back to a room off the museum floor to briefly discuss their findings and then split into groups of four or five and sent back out with “character cards”-questions about one of the six real New Yorkers the pavilions are based upon. The answers are discussed and the cards re-distributed, the searches relaunched. “The character cards focus their listening and their looking,” says Sharon Dunn, NYHS vice president for education. “They help them think about what they’re seeing, hone in on it and study it.”

That approach is “spot on,” according to Francis Schoonmaker, professor emeritus, Teachers College, Columbia University. “You can learn a lot through just interacting with materials and looking at things on your own. But part of the teaching responsibility is helping you to know what to look at, to learn how to look, how to see.”

While children from ages 3 to rs can enjoy the DCHM, the target audience is roughly 7 to 14. To engage that cohort, a strategy of “learning through empathy” emerged. “They learn through narratives and characters, not dates and events,” says Stevenson. “And learning through empathy was a big part for us because some of the history down there is kind of tough. All of the characters we chose lost at least one parent or both parents. Early on, we asked kids, what time period would you want to go to [if you could time-travel]? And a boy raised his hand and said, ‘I don’t want to go to any of them because I would be an orphan.”‘ Schoonmaker calls learning through empathy “very appropriate.”

“It’s such a mistake to try to get younger children to think about chronology,” she says. “You can do it, but is that the best use of their time? It’s much more profitable to be doing other things that will lead to their understanding. Especially if [the DCHM’s] target is fourth grade, because [from] about fourth through sixth grade they get really excited about biography.”

Dunn, who is also the former head of arts education for the New York City public schools, says, “The school programs grew out of an analysis and careful selection of the collection to help students, teachers, and museum educators illuminate the school curriculum.” She explains that the school system’s seventh and eighth-grade curriculum focuses on American history; seventh grade from pre-colonial times to the Civil War; and eighth grade on the Civil War to the present. “So it’s a wonderful teaching tool for middle school kids, too,” she says.

Kids also get a lesson in how historians often work like archeologists, literally sifting through detritus. On one wall is a cross-section of material excavated from a privy adjacent to a 19th-century bar called the Ear Inn, in lower Manhattan. The rusted tools and old shoes tell their own stories, as do the broken pieces of a chamber pot. “That gets a chuckle out of a lot of the kids,” says Skolnick.

Dunn and Stevenson will be adjusting the museum’s school program to offer four visits per academic year for each school rather than just one, allowing more kids to use more of the museum’s features and better enabling an evaluation of what “sticks,” as Stevenson puts it. “We want to know what they remember a month or two months later. Is what they are remembering ‘I had a really great time?’ Is what they’re remembering ‘I learned this thing about Alexander Hamilton; I knew about him as treasury secretary but I didn’t know he grew up in the Caribbean’?”

How has all this performed at the box office, so to speak? Vice President for Communications Laura Washington says she has no hard figures, but “the trend in attendance is up. Our goals are to maintain the boost we’ve had and to increase it. We want to attract more families while continuing to bring in school groups.”

She points to a 500 percent increase in family memberships, noting that “the renovation and addition of the DiMenna Children’s History Museum have strengthened our relationships with existing audiences and introduced us to new ones-most notably families and children, who were a largely untapped public for us before.” Washington says about 25 percent of visitors are families.

As the museum marks the completion of its first year, the staff points to one piece of positive feedback they’re quite proud of: In a ranking of the top 20 best museum exhibits by the family-oriented website Time Out New York Kids, the DiMenna Children’s History Museum finished second, behind only the dinosaur fossil-filled American Museum of Natural History, their neighbor just across 77th Street. “Which we thought was great,” says Dunn. “We don’t mind playing second fiddle to dinosaurs!”

Mark Scheerer is a New York-based freelance journalist.