This article originally appeared in the March/April 2013 edition of Museum magazine.

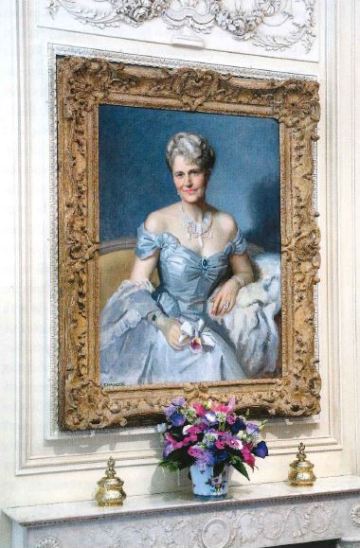

In 1955, the 68-year-old socialite and philanthropist Marjorie Merriweather Post bought a 36-room Georgian-style mansion on a 25-acre estate in the Northwest section of Washington, D.C., in order to showcase her collections of Russian Imperial art, Sevres porcelains, vases, and chalices, as well as English and French paintings, sculptures and tapestries.

Post intended to turn the mansion, which she named “Hillwood,” into a museum of these objects, and in 1977, four years after her death, that’s what it became. Hillwood is dedicated to presenting “Marjorie’s commitment to very fine objects,” according to Director of Marketing Lynn Rossotti. Visitors see objects where Post had originally placed them and relatively little changes from one visit to the next.

So why would anyone go there twice? That’s a question facing every single-artist and single-collector museum and historic house. You don’t want visitors to say, Now I can check that off the list. I don’t need to go back. One and done. Repeat visitors, who are the people most likely to become members and donors, are the financial backbone of any museum, requiring institutions to find ways to bring people through the doors again and again.

For Hillwood, as for many museums, times change. Regardless of how lovely the objects, the collections at Hillwood will always be the same, most everything in the same place and the $10 million endowment that Marjorie Post left for the museum in 1973 couldn’t be expected to underwrite all costs indefinitely. Interest income on that endowment, which rose to a height of $250 million in 2008 before falling back to approximately $175 million at present, financed the entire operating budget of Hillwood until the 1990s. By then, those funds “could no longer maintain the building, the objects and the grounds” as adequately as before, says Kate Markert, executive director of Hillwood since 2010.

In order to “grow” Hillwood as necessary, Markert says, the institution chose to spend endowment capital to renovate the mansion, build a visitor’s center and maintain the display gardens, as well as create changing exhibitions of objects from the collection and from other sources. These efforts clearly paid off: Annual have been in the same boat as the Barnes Foundation. Founder Albert Barnes placed his collection of 2,500 Impressionist, Post-Impressionist and Modern artworks in a museum in the town of Merion, Pa., on an invitation-only basis, open just two days per week. (In the 1960s, the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office prodded the Barnes, as a tax-exempt educational institution, to be a bit more accessible to the public, but entry was still quite limited; to 100 visitors per day.)

This business model hardly looked promising, and by 2002 the board of trustees, facing a rapidly declining endowment, petitioned the courts to amend the institution’s charter to permit a move to Philadelphia, where a number of foundations and philanthropists had pledged $150 million to erect a new building and endow the transplanted institution. The new facility opened to the public in May 2012 (without all those restrictions) and could not have been farther from the wishes of Dr. Barnes, who wanted nothing to do with snooty Philadelphia society. Continuing the course that he originally had set, however, was no longer possible.

Single-collector museums run the risk of being “vanity projects” (a term used by many museum directors), focusing less on the objects in the collection than on the person who acquired them. Seeing where So-and-So liked to drink his coffee in the morning and what gown Lady Such-and-Such wore to her debutante ball will probably not engender repeat visitors or memberships these days. Many believe that people need something new to see each time they visit. This is why Hillwood spends so much on its display gardens. “After one seasonal bloom is over, we tear things out and plant new bulbs, trying to keep up a level of perfection,” Markert says.

Albert Barnes’s eclectic collection of art is now on display at a new (and far more accessible) Philadelphia facility

Other single-collector museums offer amenities, special events, and exhibition programs. “What you’ll see today is substantially different than what you saw three months ago,” says Jeremy Strick, director of the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas. Raymond Nasher, a real estate developer, and his wife Patsy were both significant art collectors, focusing primarily on sculpture by American and European artists such’ as Pablo Picasso, Henry Moore, Alberto Giacometti, David Smith, Henri Matisse, Aristide Maillol, Alexander Calder, Barbara Hepworth, Claes Oldenburg and Donald Judd.

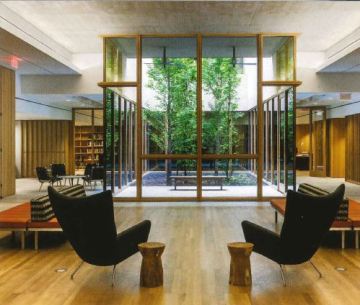

In 2003, 15 years after his wife’s death, Raymond Nasher (who died in 2007) opened his museum on a two-and-a-half acre site adjacent to the Dallas Museum of Art. Visitors can see works from his 340-object collection both outdoors and indoors. The artworks themselves are of “extraordinary quality and tell a remarkably complete, although not exhaustive, story of modern sculpture,” Strick says. Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles for nine years before coming to the Nasher in 2009, he notes that the “attitude of the public here is quite different than at other museums. At many museums of modern and contemporary art, people come in not understanding, confused by and even hostile to the works on display, but they don’t feel that here.”Strick gives credit to the attractive grounds and the “grace” of the Renzo Piano-designed building. “On a beautiful day, the Nasher is a place people want to come to, to walk around, have lunch, just relax,” he says. People come to the Nasher repeatedly not just for the specific artworks or the building but “for the general experience, the beauty of the place.”

Still, Strick believes that an active program of events is also important: “Til Midnight” concerts in the garden on the third Friday of every month, spring through fall; a music series called “Soundings”; a program that commissions contemporary artists to create temporary site-specific sculptures; “Target First Saturdays” of hands-on art activities for children and families. Amenities are a key draw, such as a cafe featuring the cuisine of celebrity chef Wolfgang Puck. The museum also “brings people in,” he says, by rotating the permanent collection and producing exhibitions of works by artists who are outside the Nashers’ collecting realm. He notes that attendance, currently 140,000 visitors per year (half of whom are repeat visitors), has gone up “every year that I’ve been here,” and memberships have increased as well. Interest income from the museum’s endowment, which is currently $100 million, funds half of the Nasher’s operating costs, requiring the center to earn the rest from admissions, memberships, donations, store sales and private event rentals.

At LeMay; America’s Car Museum in Tacoma, Wash., which opened in June 2012, the museum’s board and administration weren’t allowed the time to start up and reconsider its mission, because Harold LeMay, whose collection of 3,500 automobiles formed the basis of the museum’s holdings-left no endowment. “We have to earn our keep every day,” says Scot Keller, director of marketing at LeMay. He notes that “only 10 percent of the American population is car enthusiasts, which means that 90 percent just aren’t that into cars.”

As a result, the “strategic imperative” formulated by the museum’s board of directors involved using cars as a way of “telling a story,” through a program of changing exhibitions. In fact, more than one story is told, addressing different museum audiences. One exhibition might have an educational focus, examining topics like car technology of the past, present, and future, or how cars are made; other exhibits look at automobiles as part of popular culture, such as English cars of the early 1960s; yet another exhibit about custom detailing is aimed at car enthusiasts.

Exhibitions will change annually, drawing upon the LeMay collection. “We are going to start not with our cars and make some point about them but ask ourselves, ‘What is the story we want to tell?’ and then find the cars to tell that story,” Keller says. He hopes that this approach will lead to repeat visits: “There are over 1,000 car museums in the U.S. Many are vanity projects, and they don’t last very long.”

“Vanity” is a word frequently used to describe single-collector museums, and not in a positive way. “It is important to me that this not be a vanity museum,” says Judy Greenberg, director of the Kreeger Museum in Washington, D.C. The former residence of David and Carmen Kreeger, the museum features their 19th- and 20th-century paintings in their Philip Johnson-designed house. Sculpture-filled gardens occupy the five-and-a-half acre grounds. “We want to keep the Kreeger from being a one-and-out,” she says.

Washington, D.Cs Kreeger Museum tries hard not to be a “vanity museum,” says its director, Judy Greenberg.

Just as at the Nasher, the museum takes an expansive view of how the collectors’ tastes and artistic interests should be honored. “The Kreegers were very supportive of Washington artists and the local artistic community,” Greenberg says, which has led the museum to stage exhibits of area artists’ work. Some, such as William Christenberry and Sam Gilliam, are well-known; others are not. The Kreegers were both amateur musicians, and the museum organizes an annual three-day chamber music festival, as well as other concerts during the year. Additionally, there are gallery talks, presentations by artists about their work talks on literary subjects such as who wrote Shakespeare’s plays, programs for schoolchildren, and events for people with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers. Something is always going on.

Presenting even more challenges than a single-collector museum is an institution devoted to the work of a single artist. “We’re constantly rotating works in and out, trying to keep it fresh,” said Rosemary Roosa, director of the Walter Anderson Museum of Art in Ocean Springs, Miss. The museum receives 30,000 visitors a year, 40 percent of whom are repeat visitors. Anderson (1903-65) had a limited, and largely local, reputation during his life, and it was his friends who decided to start a museum of his work in 1991, displaying Anderson’s paintings as well as the paintings and pottery of his two brothers.

The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, which opened in 1994 and first exclusively displayed Warhol’s work, laid out chronologically, reinvented itself by the late 1990s into an institution that “tells the story of Warhol” but places his work in the context of other artists’ work, according to the museum’s director, Eric Shiner. The museum holds special exhibits of the artist’s contemporaries and those who were influenced by his work. This approach demonstrates Warhol’s importance even more effectively than displaying his work on its own. Of the museum’s 115,000 annual visitors, 35 percent are repeat visitors.

Many (although not all) other single-artist museums have followed a similar path. The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum (170,000 visitors) in Santa Fe, for instance, evolved into a center of American Modernism (with a large dose of O’Keeffe), while the Norman Rockwell Museum (125,000 visitors annually, with one-third to one-half repeaters) in Stockbridge, Mass., grew with its new building in 1993 into a center for illustration art. The Noguchi Museum (25,000 yearly visitors) in Long Island City, N.Y., now “contextualizes” Isamu Noguchi’s work, displaying it amidst the art of “those in his peer group,” according to its director, Jenny Dixon. The C.M. Russell Museum (30,000 visitors) in Great Falls, Mont., which was founded in 1953, overcame its initial single-artist focus in 2003 and started featuring the work of Russell’s contemporaries and even more current western arts and crafts. A recent exhibition was “Andy Warhol: Legends from the Cochran Collection,” including Warhol’s “Cowboys and Indians” series.

One relatively new single-artist institution demonstrates the potential pitfalls and challenges of this type of museum. Open since November 2011 in Denver, the Clyfford Still Museum operates under a mandate requiring that it be a stand-alone, (American) city-owned institution only displaying Still’s art and always keeping the collection safe and together (never selling, trading or loaning works).

Dean Sobel, director of the museum, says that he has needed to work around restrictions set down by the artist (1904-80) and his widow. “There are some guidelines in the donation agreement that are not entirely enforceable,” he says. Restrictions include requirements that the museum show only Still’s artwork, never loaning or selling any of the roughly 2,400 pieces (825 paintings and 1,575 works on paper) in its collection. “Retail is not expressly forbidden, and we will have a small area in which visitors may purchase books and other things,” Sobel says. “We are not prohibited from discussing other artists here, such as Pollock or de Kooning.”

According to the artist’s wishes, there will be no cafeteria or auditorium. The museum, however, shares a portion of its grounds with the Denver Art Museum, which has two cafeterias. The Denver Art Museum, in fact, is a key element to the viability of the Still Museum, which received no money for an endowment or general operating support. The two institutions are sharing operations such as ticketing, security and some administrative services. Many future exhibitions at the Denver Art Museum will also have tie-ins to the Still Museum collection.

The aspiration to keep an artist’s entire body of work together under one roof only makes sense if there is sufficient interest in that artist and if the estate is able to provide an endowment that covers most or all of the operating costs. One alternative is to donate portions of the collection to museums around the country, potentially offering more access to the public. “Our basic premise is to donate works,” says Debra Burchett-Lere, director of the Sam Francis

Foundation in Glendale, Calif., “to public institutions, primarily with museums and university galleries throughout the United States.” Sometimes, a deal is struck. The Houston-based Menil Collection operates the Cy Twombly Gallery, exhibiting a permanent installation of the artist’s paintings, sculpture, and works on paper, in an annex building to its main facility.

Such efforts don’t always succeed. Artist Isamu Noguchi’s talks with several Manhattan museum directors in the late 1970s and early 198os about taking possession of his artwork proved frustrating because of their unwillingness to commit to showing or even keeping his work. They wanted some artworks but not others. Noguchi “felt terribly misunderstood in his lifetime and didn’t want his work relegated to a museum basement,” says Dixon of the Noguchi Museum, where the artist’s work ultimately ended up.

Striking the right balance between a focus on the artist or the donor’s collection and the larger world (of artists, of people whose interest in a particular collection or artist is limited, of potential visitors whose first question is “what’s new?”) is tricky. But if “vanity” is a word that is used disparagingly in the single-something museum world, even worse is “mausoleum,” according to Michael Conforti, director of the single-collector Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Mass., and former president of the Association of Art Museum Directors. “The program must be varied and vital enough to keep people interested,” he says. And to get them to come back.