This article originally appeared in the September/October 2013 edition of the Museum magazine.

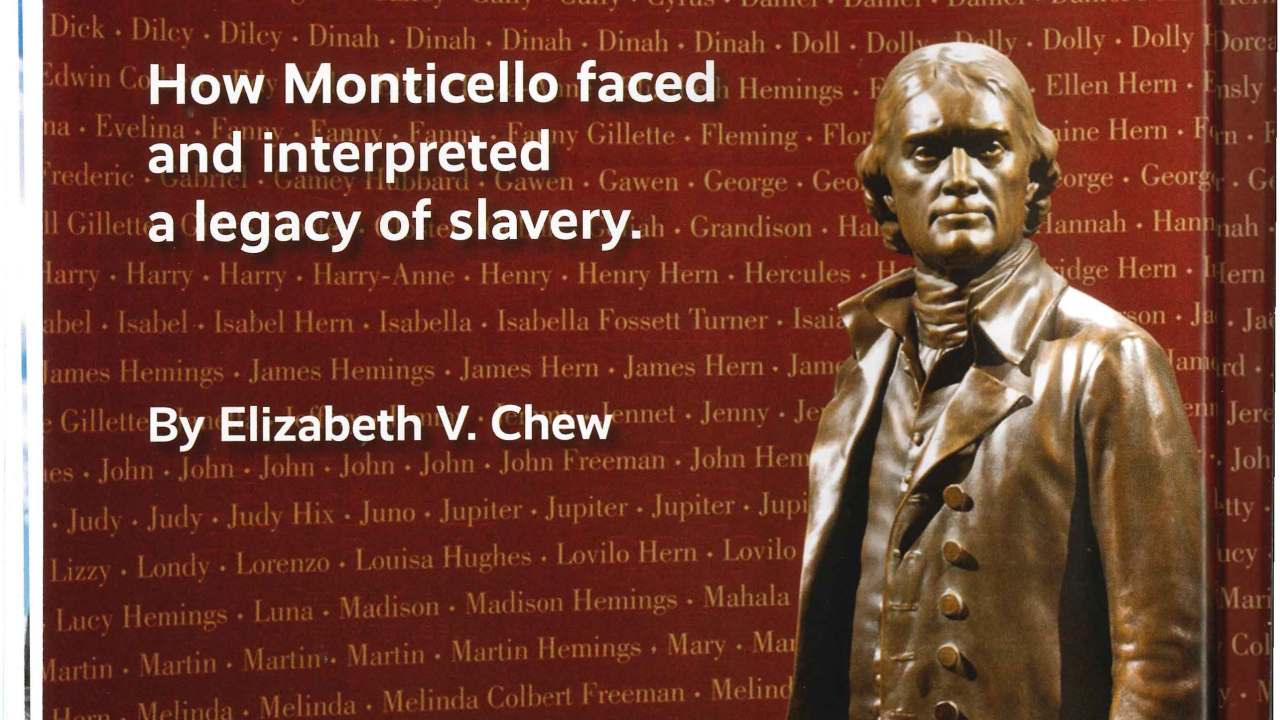

A statue of Thomas Jefferson stands before a curved wall. A sculpture of the nation’s third president certainly isn’t unusual. Consider, however, what is inscribed on the wall behind him: more than 600 names of the people the author of the Declaration of Independence held in slavery over the course of his life. This arresting juxtaposition is just one potent symbol that appears in the exhibition “Slavery at Jefferson’s Monticello: Paradox of Liberty,” a collaboration between the Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello in Charlottesville, Virginia, and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in Washington, D.C. The research that culminated in this exhibition began in the 1950s but required the leadership and courage of Monticello staff members in the early 1990s to bring it to public attention. Fundamental changes in the interpretation of slavery at Monticello made the exhibition possible-shifts that mark the latest stages in the evolution of an American cultural landmark.

The exhibition came about as a result of the friendship between Lonnie Bunch, founding director of NMAAHC, and Leslie Greene Bowman, president of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Staff members from both institutions co-organized the show based on Monticello’s so-plus years of research on slavery at Jefferson’s well-known plantation and the enslaved individuals and families who labored there. The show opened on January 28, 2012, in the gallery in the Smithsonian National Museum of American History on the National Mall where NMAAHC has been mounting exhibitions since 2009. (A few weeks later NMAAHC broke ground next door for its own building, scheduled to open in 2015.) The exhibition closed at the Smithsonian on October 13, 2012, having attracted an audience of at least 1 million. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this, the first show presented by NMAAHC on the topic of slavery, was their most heavily visited to date and that audiences were diverse and multi-generational. The show has been touring and is now on view at the Missouri History Museum through March 2, 2014.

The exhibition considers the centrality of slavery to the success of the British colonies in North America, as well as its paradox in the new American nation founded on the idea that liberty is a natural human right. It presents slavery as the unfinished work of the American Revolution, with opening sections surveying the context for Thomas Jefferson’s views on slavery as well as his action and inaction in abolishing it. The majority of the exhibition, however, focuses on six enslaved families who lived and labored at Monticello from the early 1770s to the late 1820s and their descendants.

Through documentary research and archaeological investigation begun in the mid-1950s and an oral history project launched in 1993, Monticello historians have gained a comprehensive understanding of slavery on Jefferson’s plantation, one of the best preserved and best documented in the history of the American South. Unlike many historic sites today, where slavery, due to a dearth of evidence, is presented largely as an abstraction, Monticello can paint a full picture. On their tours, interpreters introduce enslaved workers by their first and last names; discuss enslaved families over several generations; refer to specific skills, work assignments and achievements; point out the locations of particular families’ dwellings and workspaces; discuss material living conditions; and relate accounts of what happened to the families and their descendants after Thomas Jefferson’s death in 1826 and the sale of 130 enslaved men, women and children. Commitment to research on slavery by three generations of leaders and scholars at Monticello resulted in the rich material on which the exhibition is based and continues to this day with further interpretation of life on Mulberry Row and domestic life by enslaved people. (See monticello.org/mulberry-row.)

Archaeological study of Monticello as a working plantation began in 1957 under the leadership of James A. Bear, Jr., curator and then resident director of Monticello. Until the mid-1990s, archaeological fieldwork focused almost exclusively on Mulberry Row, the plantation street 200 feet south of the Monticello house, lined over time with a changing array of work buildings that supported the house, provided dwellings for enslaved domestic workers and housed workshops for slave-run industries. The majority of the people Jefferson held in slavery over the course of his life, however, were agricultural laborers living not on Mulberry Row but on the four farms that comprised the Monticello plantation. A plantation archaeological survey begun in 1997 has led to excavations enhancing our understanding of the way the enslaved agricultural laborers lived.

The excavations on Mulberry Row resulted in rich artifactual evidence for the material lives of the slaves who lived there, primarily artisans and domestic servants. Some of the items were exhibited publicly in the exhibition “Thomas Jefferson at Monticello,” which opened at the first Monticello Visitors Center in 1986. This show represented the first time that slavery became part of the overall public narrative at Monticello. Unfortunately, only 20 to 30 percent of Monticello visitors saw the exhibition, located at the offsite visitor center. The exhibition included a case of objects recently excavated from Mulberry Row and a visual representation of the weekly food ration that Jefferson gave each adult slave: a peck of cornmeal, a half-pound of bacon and four salted fish.

Documentary study of the Monticello plantation began with Edwin Betts’s edition of Jefferson’s Farm Book, published in 1953. This volume includes Jefferson’s lists, kept over 48 years, of the names and dates of births and deaths of all slaves. Bear published two early articles on Jefferson slave-run plantation industries, using data from Betts’s Farm Book, as well as archaeologically recovered evidence. Bear’s work in uncovering the contributions of named enslaved individuals has guided study of the Monticello plantation by Thomas Jefferson Foundation historians ever since.

Cinder Stanton, who joined Monticello’s staff as Bear’s assistant in 1968 and retired in 2012 as Shannon Senior Historian, has contributed more than anyone to our understanding of the whole Monticello and everyone who lived there. Her decades of scholarship have resulted in a rich oral history archive and numerous essays, recently collected in “Those Who Labor for My Happiness”: Slavery at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello.

While archaeology and documentary research on slavery at Monticello had been ongoing since the 1950s, consistent public interpretation did not begin until 40 years later. Planning for active interpretation of slavery for visitors to Monticello began in earnest in the years leading up to the 1993 commemoration of the 250th anniversary of Jefferson’s birth. Several factors contributed to this shift. Dan Jordan, who became executive director (later president) of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation in 1985, was an academic historian who provided strong support for public interpretation of slavery for the next 23 years. Jordan saw 1993 as a “watershed moment” for the Foundation and asked staff members to suggest major new initiatives. Visitor surveys indicated that the public wanted to know more about the plantation and its people. The archaeology department encouraged curators and educators to share the results of its work in public tours. And, as former Director of Interpretation Elizabeth Dowling Taylor recalls, the early 1990s was a time when other historic sites were also “getting it together” to talk about slavery.

Telling a broader multicultural story via various interpretive means, therefore, became a major component of the 1993 commemoration. Monticello staff created an advisory committee on African American history and introduced interactive guided tours of Mulberry Row on which interpreters facilitated discussion of slavery, as well as living history “Plantation Community Weekends.” Monticello also launched the “Getting Word” oral history project, for which participants researched, located and interviewed the descendants of Monticello’s enslaved families.

Research on slavery was incorporated into the house tour, the central focus of the visitor experience at Monticello.

Prior to the early 1990s, Monticello house guides received no training about slavery and had for decades followed the lead of Jefferson and his family in referring to enslaved domestic workers as “servants.” The discomfort affluent

white Southerners felt in discussing the topic of slavery was further evident in language used on signs. A text panel near the kitchen explained that food “was carried” through the all-weather passage to the dining room. By using the passive voice, the signage avoided mention of both the people doing the carrying and their status as slaves. After 1993, active stories of enslaved workers like butler Burwell Colbert and cook Edith Fossett gradually became part of

house tours.

The priorities of this generation of Monticello leaders and scholars reflected the influence of social history on interpretation at museums and historic sites at large. Interpretive efforts in American history at Colonial Williamsburg, for example, gradually extended from the political actions of elite white men in pursuing personal liberty to include the lives and roles of elite women, African Americans both enslaved and free, and, eventually, middling whites. African American history was entering the museum mainstream in the late 1980s and early ’90s, with the Smithsonian’s “Field to Factory: Afro-American Migration 1915-1940,” the Corcoran Gallery of Art’s “Facing History: The Black Image in American Art 1710-1940” and, perhaps most surprising, “Before Freedom Came: African

American Life in the Antebellum South, 1790-1865,” which opened at the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond in 1991.

The possibility of a relationship between Jefferson and Sally Hemings (1773-1835) entered public discourse in 1802 and has remained a subject of discussion and disagreement ever since. Though many prominent historians initially found the argument unpersuasive and Monticello tours did not acknowledge the subject for many years, strong family oral histories had long led the descendants of Hemings’s sons Madison and Eston to claim that Jefferson was their ancestor.

The next big moment in the interpretation of slavery at Monticello arrived when a DNA study published in the November 5, 1998 issue of the journal Nature confirmed a genetic link between the Jefferson family and the children of Sally Hemings. Following the article’s publication, Jordan formed a Monticello staff committee to study the evidence. Despite strongly voiced opposition both locally and nationally and a dissenting opinion authored by one committee member, the Foundation announced its position in January 2000. Based on a combination of the DNA study, documentary and oral history, and statistical probability, the Foundation agreed with growing scholarly consensus that Jefferson was the father of Sally Hemings’s six children. Implementing the change in outlook was initially difficult because many guides were uncomfortable discussing it, but Jefferson’s paternity of Hemings’s children nevertheless became part of tour narratives.

In developing the show, we decided to follow the trajectory of all this research and experience to focus on the agency of the enslaved rather than on Jefferson’s inaction or hypocrisy. The primary reason for this decision was the rich material culture supporting it. In addition, we believed public audiences at the Smithsonian and elsewhere would respond to the many remarkable stories of the ways individuals and families survived slavery and passed their histories and convictions to succeeding generations. In the exhibition, most of the space was devoted to the presentation of the six enslaved families in as much detail as possible-surviving objects made by them, archaeologically recovered objects associated with their work or living locations, family trees, a video and written labels-reflecting the multidisciplinary nature of Monticello’s work on slavery. It was important to us to connect objects, even partial ones, with real people living in slavery whose stories we could tell. The fragmentary nature of the objects is part of the story.

In turning the history of plantation slavery in early America into a series of stories about individual families at

Monticello, we hoped to give a human face to the institution of slavery, which attempted to deny people their basic

humanity. Though we have only a handful of photographs or first-hand accounts of anyone who lived in slavery at Monticello, we do now have a rich archaeological and genealogical record. We debated whether ceramic sherds and pieces of metal dug out of the ground would be evocative for visitors. We as curators thought they were and

believed that showing the material lives of slaves along with their narrative stories could be illuminating.

Enslaved families at Monticello earned small amounts of money by keeping gardens and poultry yards and making items such as brooms, all to sell to occupants of the main house. Record books from across the decades of Jefferson’s life at Monticello show him and members of his family regularly purchasing ducks, chickens, eggs, b.sh, vegetables and many other items from named slaves. Archaeological evidence confirms account books’ indications that slaves stored summer produce for sale in winter. By the end of Jefferson’s life, when money was scarce, his granddaughters borrowed money from one slave to pay another. Enslaved people had other ways of earning money as well. Jefferson gave cash incentives to enslaved craftspeople to increase productivity. He also paid slaves for extremely unpleasant tasks like cleaning the sewers under the privies, and visitors sometimes tipped slaves. With the money they earned, surviving shopkeepers’ accounts tell us, enslaved people frequented local stores on Sundays.

Archaeology confirms that slaves had possessions far beyond what slaveholders gave them. At Monticello and across the Chesapeake, excavations have unearthed imported tablewares, fashionable metal buttons and other fasteners for clothing, jewelry and other items of personal adornment, personal care items like bone handles from toothbrushes, and tools. The existence of these objects speaks loudly of the tenacious ability of human beings living in slavery to negotiate continual small improvements in living conditions. It shows how enslaved people worked towards a way out of no way.

The final section of the exhibition presents some of the stories of the descendants of Monticello slaves. For example, Elizabeth Hemings, matriarch of the Hemings family at Monticello and mother of Sally, had eight descendants who fought for the Union in the Civil War, four in white regiments and four in black regiments. Stories of families divided by different choices about racial identity are common among the descendants. Some stories are almost unbelievable. For example, William Monroe Trotter (1872-1934)-a great-grandson of Monticello head blacksmith Joseph Fossett and Monticello head cook Edith Hem Fossett-was a Harvard graduate who became the editor of the Guardian, a black newspaper in Boston, and an early civil rights activist. With WE.B. Du Bois, he was a founder of the Niagara Movement, a precursor of the N.A.A.C.P. His descendants participated in the civil rights actions of the 1960s.

Voices of descendants interviewed for the “Getting Word” oral history project are available in a short f:tlm as well as via the “Getting Word” website at kiosks in the exhibition. One of the most powerful statements came from Virginia Craft Rose (1913-2011), a Fossett family descendant and niece of William Monroe Trotter: “We couldn’t forget slavery, but we could overcome it. That was the theme of our family.”

Elizabeth V Chew is former curator, Monticello, Charlottesville, Virginia, and currently director, curatorial and education division, Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.