This article originally appeared in the September/October 2013 edition of the Museum magazine.

An excerpt from Magnetic The Art and Science of Engagement, The AAM Press, 2013.

In the AAM book Magnetic: The Art and Science of Engagement, (2013, The AAM Press) authors Anne Bergeron and Beth Tuttle examine what they call “magnetic” organizations – those that have developed an energized core centered on people, vision, and service, which enables them to attract and retain critical resources. Following is an adapted excerpt from the book as previously published in the September/October 2013 issue of Museum magazine.

FOR MORE THAN 30 YEARS, Jim Haynes, a Louisiana-born entrepreneur, travel writer and retired University of Paris professor, has hosted Sunday dinner at his apartment. Each week he opens his Paris home to the first 50 people who write or e-mail him and ask to attend, regardless of whether he knows them or not. In fact, more often than not, he does not know his guests, nor do they know each other. Yet they come from all over the world for food, conversation and the opportunity to meet the “friends they haven’t met yet,” according to Haynes.

The reason Haynes hosts and coordinates his weekly feasts is his abiding belief in the power of connection and how the consistent practice of this simple and enjoyable tradition has enriched the lives of others. In a not insignificant way, he has helped to change the world by engaging people with one another across vast divides of demographics, geography, culture, and belief.

Despite no office, infrastructure or advertising, more than 140,000 people have found their way to this Sunday meal, drawing others into the circle. While Haynes’s home is not a museum, his weekly salon is clearly magnetic and illustrates many of the characteristics we found in Magnetic Museums.

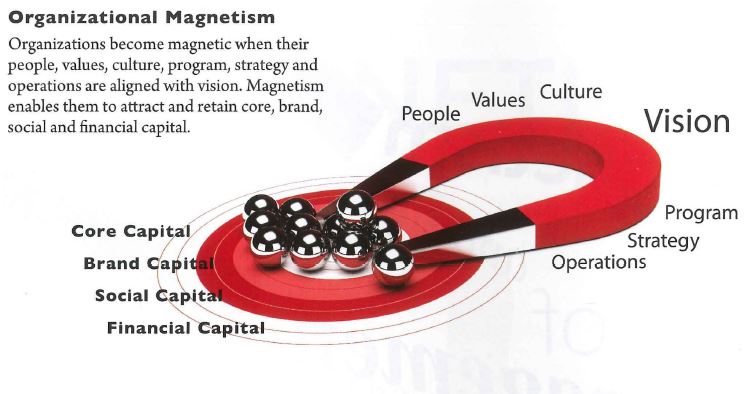

What makes Magnetic Museums different from the rest of the field is that they exhibit a powerful ability to attract and retain the four types of capital needed for museums to conceive, develop and deliver superior exhibitions, programs and experiences to their audiences: core, social, brand and, of course, financial capital Like Haynes, Magnetic Museums inspire loyal communities of people who are tightly bonded by a belief in the value, mission imperatives and vision of these institutions. Like a magnet, they exert a “pull” that can almost seem magical. But as any high school physics student knows, magnetism isn’t magic; it’s science.

The Art of Engagement

While the laws of physics and the universe control the behavior of electrons, people are motivated by emotions and reason. This is where the art of engagement comes into play.

Engagement is a powerful word. It means connecting one person or thing to another; making a promise, perhaps to meet; entering into an emotional involvement that might lead to marriage; or joining forces, like gears in a machine, to create motion or energy.

Over the past two decades, museums have made advances in the levels and kinds of engagement they pursue, and with whom. A Google search for “museums + engagement” delivers an impressive 9,510,000 results in 0.33 seconds. And a review of the literature on museum audiences reveals the depth of thinking on how to enhance visitor learning, experience and enjoyment through engagement techniques.

In 2002, AAM issued its report, Mastering Civic Engagement, that challenged museums to think about their roles and responsibilities in relation to the communities they serve. And in 2010, Nina Simon discussed in The Participatory Museum what she saw as a need to provide meaningful ways for visitors to contribute to and co-create the museum experience. What we found in our study was a group of institutions that have knit these lessons together and internalized a culture of engagement, participation, and service, reaping impressive benefits as a result.

Magnetic Museums are both engaging and engaged places. They are highly people-centered organizations. They thrive on a fundamental desire to connect people with the subjects, ideas, and objects that inspire passion, curiosity and learning. They focus on creating meaningful experiences that have emotional resonance, which, in turn, serve to create fulfilling relationships. Moreover, Magnetic Museums care equally about engaging internal and external audiences, as well as the communities they serve. To echo Stephen Weil, they are both “about something” and “for someone.”

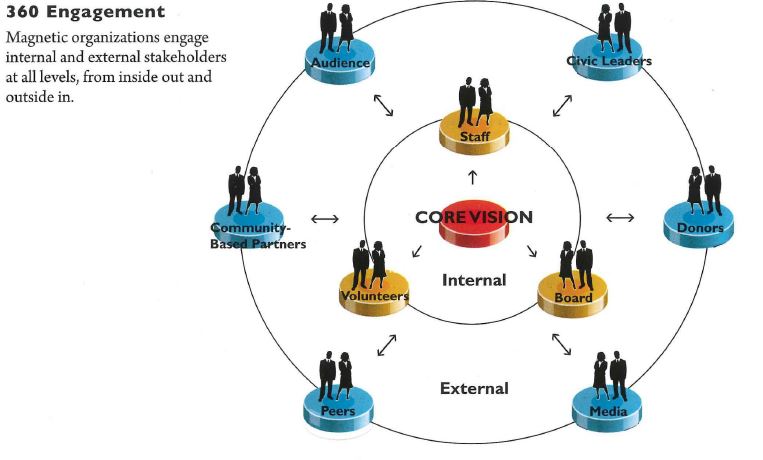

Magnetic Museums also widen the circle of involvement at every opportunity, practicing what we call 360 engagement. They are inclusive, open-minded and open-hearted organizations. They work from the inside out, starting by engaging staff, board and volunteers, followed by donors and members, community leaders and organizations, and of course, on-site audiences, as well as those in the virtual world.

Magnetic Museums have found their strength by embracing the “service” aspect of their public service roles. By committing their institutional assets unconditionally to meeting the needs, empowering the efforts and enriching the experiences of the people and communities they serve-whether employees, trustees, donors, volunteers, civic and community partners, or, especially, audiences-they ultimately generate the relationships, reputation and resources that enrich their institutions.

The Magnetic Museums in Our Study

Tucked into the middle of the country, the Philbrook Museum of Art was once a remote preserve for the wealthiest citizens of Tulsa, Oklahoma. Today it teems with families, children, and an ethnically and economically diverse audience ranging from first-time museum visitors to sophisticated connoisseurs of art. It is also an institutional partner to more than 20 organizations in the city, from the local library to the food bank to the public schools. The Philbrook became a vital urban asset in a relatively simple way: by adopting an inspiring, shared vision for the museum based on building community through access, service, collaboration and engagement, and aligning everything it does with achieving that vision. The Philbrook has reframed its approach to collections, exhibitions, gallery interpretation, educational programming and even media outreach, markedly impacting the diversity and size of its audiences. When colleagues say incremental change is all one can expect, especially in terms of audience diversity efforts, Randall Suffolk, director of the Philbrook, replies, “Not if you really commit to it and make inclusivity part of your institutional DNA.”

Then there’s Conner Prairie Interactive History Park, a living history museum that shines a bright light on Indiana’s 19th-century past. It is also an organization that survived a life-threatening two-year governance dispute only to emerge stronger than ever. How? By emphasizing visitor engagement. The museum reoriented its focus to regard audience members as “guests” and put them at the center of every decision affecting participation and planned activity. Its award-winning approach, called “Opening Doors to Great Guest Experiences,” has produced in six years a 58 percent increase in attendance, a 22 percent increase in membership, and a 40-plus percent increase in ratings for visitor satisfaction and quality of experience.

A financial crisis in the mid-1990s turned out to be a turning point for the Chrysler Museum of Art, and the leadership transition that followed allowed the Norfolk, Virginia, museum to reinvent itself. A new mission to foster transformative experiences through art, a dedication to serving the area’s diverse community, especially its African American population, and a commitment to fiscal responsibility have combined to galvanize the staff and board. Fostering a highly empowered, service-oriented culture has not only transformed the Chrysler into a welcoming and participatory museum, it has created an extraordinarily loyal and motivated staff and board culture.

More than a decade ago, the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh (CMP) was only a small organization with big ambitions. In the intervening years, it has nearly quadrupled in size, multiplied its offerings, nearly tripled its membership and attendance, and more than doubled its annual operating income, making it the fastest growing institution that we studied. What fueled this growth? Articulating a powerful agenda for children and inviting others to contribute to realizing that agenda. From humble beginnings in the basement of a former post office building, CMP is now a recognized leader in the museum field and is the heart and centerpiece of a campus for children and families in Pittsburgh. By widening its circle of interaction, support, and influence, it has become a catalyst for the redevelopment of Pittsburgh’s North Side through collaborations that have strengthened the capacity and connectedness of dozens of community-based organizations.

The Greensboro Science Center (GSC) in North Carolina joined civic, business and nonprofit leaders in rebuilding

the economic vitality of a city that had never fully recovered from an onslaught of 1980s corporate downsizing. Embracing the business recruitment efforts of the Action Greensboro consortium, GSC focused its activities to enhance educational opportunities and quality of life initiatives, becoming a leading destination for cultural tourism in the region. It also solidified its position as a frontrunner in science education for elementary, middle- and high school students. Residents responded resoundingly to the museum’s intentional community focus, not only showing up in droves but also approving a $20 million bond to build a state-of-the-art SciQuarium for the study of diverse aquatic ecosystems.

The oldest and largest of the museums we studied is The Franklin Institute. Change often comes slowly to large-scale organizations, but creating a business-savvy, people- and performance-focused culture has enabled the institute to broaden its audience, expand its service to the community and enlarge its base of support. Welcoming more than 800,000 visitors to its historic building each year is only a start. The institute also founded a science-focused magnet high school, engaged teens in out-of-school science education and career preparation programs, and became the leading source for science education in Philadelphia and beyond.

Six Practices of Magnetic Museums

The first and most important insight to emerge from this study is that there is no trump card to be played, no silver-bullet solution in the quest to becoming a Magnetic Museum.

The strength of the Magnetic Museum emerges only when multiple practices are deployed. Although not all of the museums we studied were equally strong in all areas, each of them exhibited capability in a majority of the categories that we identified. All are working towards a model in which these focus areas, taken together and pursued in a coordinated fashion, become a defining organizational philosophy in which each practice reinforces and enhances the power of the others.

The second insight is that there are few shortcuts on the path to becoming magnetic. It takes time to change organizational culture, and time to build relationships and trust. Each of the museums we studied evolved over a period of five to 15 years, with stable leadership in place. All say the process continues today.

We identified six practices common to Magnetic Museums. These institutions:

1. Build Core Alignment

Magnetism starts at the core when strong alignment is created within the professional staff and board around a shared vision, mission or compelling set of long-term goals. This internal alignment is the necessary condition for becoming magnetic and sets the course for the organization’s transformation. Leaders of Magnetic Museums are relentless in their efforts to enlist others in helping to make the institutional vision a reality. While it may take some time for vision to permeate a complex institution, positive energy begins to flow as soon as a core group of staff and trustees comes together behind a powerful idea or goal and begins to consistently communicate its passion, making the vision visible to others.

2. Embrace 360 Engagement

Magnetic Museums practice 360 engagement, involving internal and external stakeholders in meaningful experiences that make a difference for both the individual and the institution. By doing so, these museums strengthen and expand the reach of their “magnetic fields” by drawing more people in, creating more powerfully charged connections and aligning them more closely with the work of their institutions. Magnetic Museums understand that emotional engagement is a catalyst for action and advocacy. Creating personally meaningful experiences while providing opportunities to participate, contribute and make a difference builds a sense of common purpose, efficacy, and loyalty that inspires everyone to do more.

3. Empower Others

Magnetic Museums are motivated by a people-first, service-first philosophy that seeks to meet the needs, develop the leadership and activate the potential of others. They cultivate and empower many leaders within their ranks, and have loyal and often long-tenured executive teams. Authority and information flow freely between the trustees and directors, who work in genuine partnership towards a common goal. Each has a distinct role and responsibilities that support clear boundaries between governance and management. Widespread empowerment is enabled by a high degree of internal alignment and the clear sense of direction that results.

4. Widen the Circle and Invite the Outside In

Magnetic Museums widen their circles of engagement and, as a result, widen their circles of influence. They operate from a fundamental principle of respect for what others can contribute, whether they are community or cultural partners, funders or civic leaders, subject matter advisors or audiences . . They personify openness and inclusiveness, and value transparency because it is the foundation of trust in relationships. They freely share their resources, expertise and talent, and readily partner with others willing to do the same. By turning outward, inviting outside perspectives and working with multiple partners at the earliest stages of idea development, Magnetic Museums create shared ownership in ways that seeking after-the-fact buy-in can never accomplish.

Magnetic Museums also connect people to each other around ideas, issues, and experiences. Whether serving as gathering places, creating opportunities that bring disparate audiences together, or facilitating virtual or in-person communities of interest, they forge relationships with and among people. They leverage the power of networks not only to advance their institutional missions but also to create a stronger social fabric within their communities.

5. Become Essential

Magnetic Museums overcome one of the central challenges facing cultural institutions today: becoming essential. By increasing their relevance, responsiveness, and value in mission-related ways, they become more meaningful, useful and pertinent to daily life in their communities. They recognize the importance of meeting real needs that reflect authentic community priorities. Magnetic Museums intentionally seek out and invest in the points of intersection between the institutional vision and the community vision.

6. Build Trust Through High Performance

Magnetic Museums are high-performance organizations that build trust over time by consistently delivering superior results. These organizations have high ambitions and attract people who are similarly motivated to be the best at what they do, which can be particularly valuable in terms of staff and board capacity. They appreciate and reward talent, recruit for cultural fit as much as for skills, and invest in developing their people. They are disciplined about planning and financial management. They set, meet and frequently exceed goals. They value data in their decision making, benchmark performance, measure progress and adjust course as necessary. Magnetic Museums are adaptable and imaginative, especially when facing constraints or challenges. They embrace experimentation and failure as part of daily learning and improvement. Because of their consistent performance, they are viewed as good investments. They are places that inspire, connect, ignite and serve.

Anne Bergeron is associate director of external affairs, Dallas Museum of Art. Beth Tuttle is president and chief executive officer, Cultural Data Project, Philadelphia.