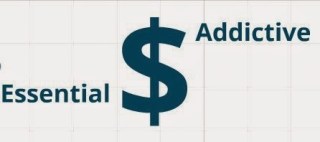

I’ve been using this graphic in talks lately when talking about successful financial models for museums. The point being that if your organization provides experiences or services that are addictive or essential, or better yet, both, you have the foundation for a successful business plan.

“Essential” encompasses stuff at the bottom of Maslow’s pyramid: food, shelter, sleep, human relationships.

If you need an example of “Addictive,” consider the Massive Multiplayer Online Game World of Warcraft. Could people live without it? Presumably. But as a species we’ve already spent, collectively, over 6 million years on the game, so evidently we don’t want to.

Somehow, as clear as this classification scheme seems, the conversation often veers off track when I ask museum staff to slot what their organization offers into these two categories.

Me: “What do you do that is essential?”

Staffer: “Arts education.”

Well ok, I wish we lived in a world where people worked art into their household budget right up there at the top with buying enough groceries for the week, and getting shoes for the kids to go to school with. But I think we don’t. (Otherwise we wouldn’t have needed a national campaign to try to convince the public of the need for arts education.)

Granted, “essential” is a tough one for our field to tackle. Museums don’t usually think of themselves as social service agencies, though some tackle food deserts, run soup kitchens (of a sort), even provide a neighborhood laundromat. I suspect our most promising pitch for casting ourselves as essential community resources focuses on our role as educational organizations. But in conversations on education, museums are referred to, dismissively, as places for “informal” learning, so that argument isn’t a sure fire winner, either.

The fact is, most of what museums do we hope will be addictive—creating a desire so intense people are willing to allocate scarce time & money to scratch the itch. Sometime, unfortunately, the itch they scratch is our passion to create a particular exhibit, program, building or whatever.

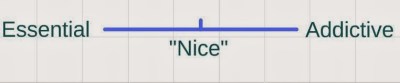

I admit that categorizing everything as either “addictive/essential” generalization oversimplifies the world. Let’s make the exercise a little less “either-or” and redraw the figure as a scale

To figure out a workable business model for anything a museum wants to support, first place it accurately on this spectrum of “essential to addictive.” Probably most things won’t be either as essential as sleep or as addictive as WOW—they’ll be somewhere in the middle.

You know what’s dead smack in that middle? “Nice.”

The worst place to land is “nice.” Nice gets a pat on the head. Nice is what gets cut first when funds from any source are short.

So how come museums end up creating so much nice stuff? How come we so often we have the luxury of scratching our own creative itch? Maybe because nonprofit economics are different, in a significant way, than those governing for-profit business plans. Nonprofit income isn’t a simple line from producer to consumer. It’s a triangle, with the third player being people or organizations willing to underwrite that transaction. Funders may think that consumers ought to want, or need, the experience, good or service a museum is providing, whether or not the consumers in question agree.

If a funder’s assessment is inaccurate—the consumer doesn’t think what the producer offers is addictive or essential—that funder isn’t doing the museum any favors in the long run. Their support may merely encourage the museum to invest resources in something that is fundamentally flawed. Something “nice.”

How can we avoid bad decisions that are premised on funders’ presumptions about what people ought to want or need? One radical approach is to eschew prescriptive solutions altogether. Some people are proposing that the best way to fight poverty, for example, is to just give cash to poor people. That approach is even coming out well in some real world tests.

If the US, instead of creating an elaborate system of food stamps and housing assistance and head start, etc., etc., emulated the proposal recently floated in Switzerland and simply provided adults with a minimum monthly income, what would they spend it on? How much income would a family need, on average, before they started to budget for things that museums provide? Great question, to which I wish I had the answer.

For now, since museums are buffered by government and philanthropic support, it can take years, or decades, of slow economic decay for them to find they have put together a bundle of offerings people don’t want, or need, enough to pay for.

So try a bit of brutally honest introspection next time you tackle organizational planning. Put a line up on the wall, with “Addictive” at one end and “Essential” at the other. Start pinning your products, services, programs where you think they belong. Make sure you have some people in the room (on staff or outside recruits) who bring a fresh eye and fearless skepticism to critique the placement of your tags.

And everything that lands on “nice?” Take a hard look at what it costs you to provide these nice things, and rethink whether they belong in your plan at all.

Well, I know nice girls don't get the corner office, for sure. And the moving from nice to necessary has been a shorthand argument kicking around for several years now in leadership discussions. Many museums I know are demonstrably necessary to their communities: ECHO, Burlington, Children's in Omaha, Strawbery Banke, Portsmouth, many others and their business models are working. WOW interests me as Jane McGonigal http://janemcgonigal.com drew a line at the opening Center for the Future of Museums lecture from gaming to museums to happiness declaring that games and museums provided the 4 qualities necessary for happiness: meaningful work, mastery over the work, opportunity to work with others you respect, and opportunity to work on something larger than yourself. The difference for the museum audience, I think, is the open ended-ness, the lack of defined levels, or the lack of challenge at a museum. Maybe we call it free choice learning? Maybe the gaming world calls it Second LIfe. Addition involves the brain specifically, and not in a good way. For an eyeopening exploration of a rabid fan base see Warren St. John's Rammer Jammer Yellow Hammer's riotous examination of U/Alabama's football fans. Roll Tide. And by the way, they don't financially support the team as they spend all their money in other very specific ways.

This comment is posted on behalf of Anne Bergeron & Beth Tuttle:

What we found in our research on Magnetic museums is that organizations thrived when they aligned themselves with essential needs in their communities, even amidst the recent economic downturn. By creating meaningful relationships with their various publics, they also attracted increased visitorship, investment and support. They engaged in what Glen Holt, formerly of the St. Louis Public Library, calls "activist missions" that are attuned to and fundamentally address real community needs. We might not go so far as to call their actions "addictive", but they certainly moved from being nice cultural amenities to critical community resources.

I would argue that to use the word "addictive" is completely misguided, because as Mary says, addiction is a brain disease–and I will add–an incurable one with very devastating outcomes. While people can be addicted to things that are good for them, it is almost impossible to see or hear the word "addictive" and think of positive actions or outcomes. The fact that you use these diagrams in your presentations and blog post suggests you agree with the analogy and metaphor, but it is hard to tell because your comment is posted on behalf of Anne and Beth. But since you posted the blog, I have a question: can you explain the logic behind the continuum? A continuum is usually logical, and I don't see the logic behind this one.

Thanks for the great list of "necessary" museums, Mary. Regarding my use of the word "addiction," (per your comment, too, Randi), I chose it in preference to a milder word, such as "compelling," because people head too easily down the path of watering it down still further. I stand by "addiction" in it's definition as "an intense desire for some particular thing." While there certainly are a host of damaging addictions, I would like to work on a future where our "intense desires" are for experiences that are psychologically and physically good for us.

As to the scale I am using, Randi, I know you are a professional evaluator, but I'm not proposing to turn this into a Likert scale for a formal survey instrument. I think most people could peg an experience as to where it falls on the "essential to addictive" spectrum. What kind of scale would you create if you were turning this into a survey question?

Maslow's hierarchy of needs does indeed imply a progression–one cannot achieve the higher levels if the fundamentals of food and shelter are not met. But everything in the ranking is still a human need. We are not fully human without the qualities that are at the peak of the pyramid. Museums surely can argue their importance in helping to foster those qualities, such as a creativity, spontaneity and problem solving. This begs the question of why M's original hierarchy should not be the scale when we ask donors for support, or try to determine our own organizational priorities. If addiction is defined as an intense desire for a particular thing, heaven knows we would all rather be in the fortunate place of not needing to desire food, clean water, shelter, etc. vs. having a passion instead for self-actualization.

Beth, I wasn't even thinking about a survey when I posed the question. Simply looking for logic–and I don't see the relationship between essential and addictive, nor do I see "nice" as being in the middle. If anything, "nice" would be on one end of the spectrum and essential on the other. "Essential" is very meaningful and well understood; "addictive" has too many other (negative) connotations (now I am thinking like an evaluator-only because I seek clarity of thought). How would I design a survey question/scale–I would need to know what you want to measure.

My point as well, Randi. All of Maslow's hierarchy of needs fall in the realm of essential to be fully human. Mere survival (the baseline needs) does not equate to being human. And self-actualization (the top of the pyramid) does not equate to addiction by any stretch. The scale as sketched with "essential" and "addiction" at the extremes, and "nice" in the middle becomes an exercise in semantics, and does not seem especially helpful to me in trying to make the case for a donor's support.

As someone who has coordinated a music series in Second Life for 7 years (http://hplusmagazine.com/2012/09/19/invited-essay-future-of-work-musical-performance-in-virtual-reality-music-island-five-years-of-virtual-concerts-in-the-park/) I certainly saw red at some of the comments here. . . the idea that virtual worlds being dismissed as "addictive and not in a good way" and I could go to great lengths on how virtual worlds are mis-categorized as games, in that they serve only as a platform for creativity and do not have the goals and rewards programmed by game algorithms as they are in games like WoW. The muddled thinking here amazes this gamer girl! Look no further for why the digital world eludes you!

However the point of this article is likely to shake us up and have us talking and I guess it has done that!

Getting back to the algorithms in true games, game theory has used psychological research extremely profitably to use adrenalin pumping challenge and copious rewards to control human behaviour. Is that the sort of thinking we want to use in our cultural programming? I find that idea very Orwellian. And of course even if you embrace that idea you have to deal with the fact that the metrics are very different in FPS or MPORPGs. Which would fit a museum educational program? The mind boggles.

The only positive takeaway from this article that I can see is to be able to frame the "essential" value of our work. So, for example, I don't just "write grants to raise money for the arts" but I "enable programs that empower equity seeking groups with artistic access and voice".