This article originally appeared in the January/February 2015 edition of the Museum magazine.

WHILE CIVIL RIGHTS MUSEUMS take the viewer on a journey from hate to hope, the experience at a new digital painting exhibit staged by the Bowdoin College Museum of Art is ultimately more benign—at least on the surface. But “Fifty Years Later: The Portrayal of the Negro in American Painting” (bcma.bowdoinimg.net) tells a powerful story on canvas, expressed with an artist’s deft strokes and compelling vision.

The online exhibition reprises the landmark exhibition staged in 1964 by the museum’s innovative curator, Marvin S. Sadik. Though physically removed from mass marches and civil rights demonstrations, Sadik and others at this rural campus in Brunswick, Maine, heard echoes of the call for racial justice.

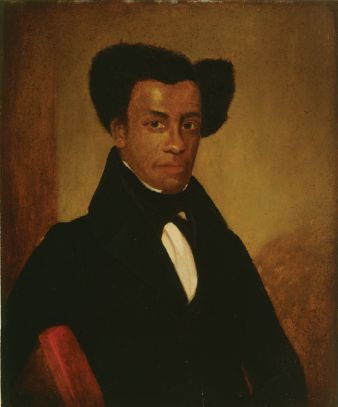

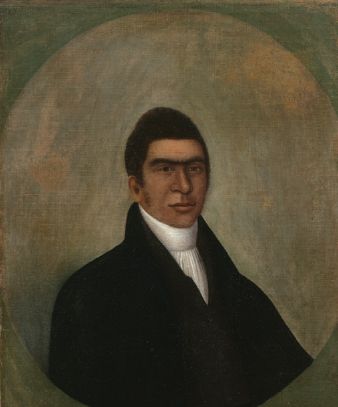

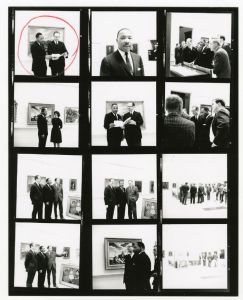

The net result was a collection of 80 paintings spanning 250 years, assembled from top-tier museums and private collections. The show was one of the first to survey American paintings representing African American subjects. Among the artists: Henry Ossawa Tanner, Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer. Among the distinguished viewers: the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller.

Realizing that it would be virtually impossible to restage the exhibit physically for logistical and financial reasons, Bowdoin Curatorial Fellow Sarah Montross and her colleagues concluded that only a virtual presentation would be feasible. The exhibit is supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, but the time investment was generally more demanding than the need for funds. On this 50th anniversary of the civil rights movement, Montross believes Sadik would appreciate the resulting intrinsic value.

“It’s a quirky exhibition. There is wonderful art in it, but there was also a strange blending of artists. Not only … African American artists, but … European [and] American artists who were producing art that engages in the question of the role of the African American in painting,” says Dana Byrd, an art historian on the Bowdoin faculty.

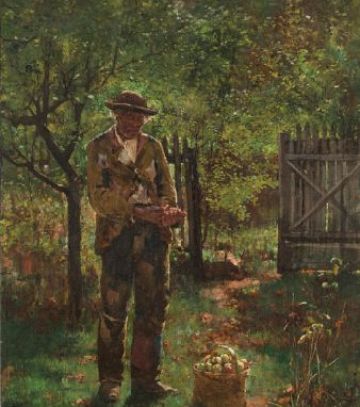

In his selections, Sadik largely avoided controversial themes, instead favoring portraiture, landscape art, musicality and domestic tableaus. “He didn’t want to include caricature, although some of the paintings probably veer toward that,” says Byrd. “He was deliberately choosing a more positive historical representation.”

Still, it would be inaccurate to say the curator or the artists avoided controversy or splashed gesso on the truth. Thomas Eakins’s Whistling for Plover shows an African American man crouched in a field with a rifle in his hand surrounded by fallen duck trophies. His brilliant white shirt stands out against a stark landscape as he waits for his hunting dog to return—or for the moment to be his? Plantation Road, in Thomas Hart Benton’s vision, is a place where the labor of black workers is harsh, the landscape barren. They work under a cold blue sky and skeletal clouds rise as if in rebuke.

Today’s exhibit developers chose to display the paintings in their original sequence rather than creating a 3D online gallery environment, according to Jen Jack Gieseking, who engaged other students to assist with the exhibit update. “We especially hope that the incredible work done by our students is fully acknowledged,” says Montross. “Without [them] this website could not have happened.”

The high-quality images were provided from a number of institutions to build the final product. Eerily relevant given recent events in Ferguson, Missouri, is the exhibit’s final work, Jack Levine’s Birmingham ’63. An abstraction in brown, black and white shows what appears to be an African American family surrounded by barking dogs with teeth bared. Is Dr. King standing in the background or is it the authorities?

Each generation must discover how it will interpret the crucible of race relations. Thanks to the new Bowdoin exhibition, there is an opportunity for everyone to be a part of the story. — Jeff Levine