This article originally appeared in the July/August 2015 edition of Museum magazine.

On May 30, 1899, a struggling young inventor wrote the Smithsonian Institution asking for help: “I am an enthusiast, but not a crank in the sense that I have some pet theories as to the proper construction of a flying machine.”

Wilbur Wright received a letter back dated June 2 that year with recommended readings on “aerial navigation”—certainly a quick turnaround for the time. Had Wright made the same request today, he would likely have done so online, where the response is virtual and virtually instantaneous, mining vastly greater depths of information than anything available then. Nor would such a quest for aeronautical advice be limited to any particular entity, as museums here and everywhere willingly share their treasured resources with anyone who can tap out a URL on a keyboard. Institutions from the de Young Museum of fine arts in San Francisco to the Fort Worth Museum of History and Science to the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, are using digital resources to facilitate distance learning, bringing their resources to vast and varied audiences.

“All museums should reexamine the role that they play in learning, both in their geographic communities and in their digital reach and assess how they can increase the depth of their impact,” said former Alliance President Ford W. Bell at a national conference focused on digital transformation in museums last September. Some 200 hundred experts and thought leaders participated in the event, sponsored by the Fort Worth Museum of History and Science.

Wilbur Wright’s letter, wrinkled and stained with age, is now one of millions of artifacts in the Smithson’s online collection—a talisman of the transition from the mechanical to the information age. It stands as a monument and an urgent reminder. “We’re only at the beginning of this wave of technology, and it’s really going to dominate our approach to learning in the next few decades,” says Smithsonian Secretary Emeritus G. Wayne Clough. “We’ll learn how to do it better. And if you sit around and wait until it’s already happened, it will be too late.”

Back in 2009, seeing the inevitable, Clough spearheaded “Smithsonian 2.0,” a digital initiative with dual goals: protect the Smithsonian’s artifacts from damage from too much physical handling and simultaneously build outreach to new audiences who could only enter the institution through an information portal. “Here is a resource that’s paid for by every taxpayer in the country, [but] you can’t expect everybody to make a trip to the Smithsonian every year. So the way you compensate for that is you deliver the materials, the richness of the Smithsonian digitally,” he says.

Distance education means more than providing pictures of things. Museums must also explain them so the online experience is value added. Thus the Smithsonian started collecting metadata, and Clough accessed experts in Silicon Valley to build programs that allow the public to read details about an item within three days of entry. Some 4,000 volunteers are now engaged in this process, accelerated by rapid-capture pilot projects. A good example is the Smithsonian’s collection of 66,000 bumblebees (probably safer to view via computer than in person!), each pictured online with two descriptive tags.

In 2014, some 28 million readers plunged into the Smithsonian’s pool of digital information, and they didn’t want to stay in the shallow end. “Access to information is not the problem anymore,” says Carrie Kotcho, director of education and outreach at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, an early adapter of digital technology and distance learning. “Do you know the facts? Do you know the year? Do you know the name? Do you know the event? It’s what the significance is. Why did this happen? How does this relate to me today? How does this relate to what America is now or could be in the future?”

Among the history museum’s relatively new course offerings for K-12 students are MOOCs (massive open online courses). One on “Superheroes in American History” has attracted some 40,000 registrants, with an additional 2,000 seeking a certificate. The program stops short of offering academic credit, but the Smithsonian is headed in that direction, backed by a teacher advisory group. “All the technologies are exciting. We need to keep track of what’s going on and stay ahead. It’s all about using the best technology to meet the needs of the audience,” says Kotcho.

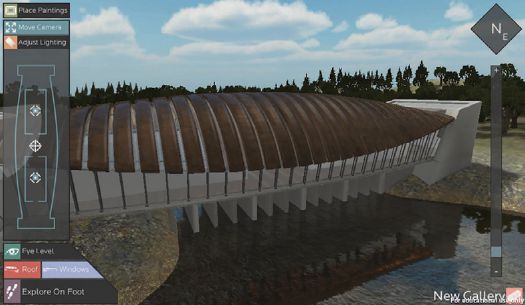

A pilot online course at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art brings the collection to high school students in rural areas.

Some institutions are already getting that message. Distance education delivered via digital resources is turning the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art’s collection into a classroom for students seeking academic credit and greater understanding of the arts. Anne Kraybill, who directs the museum’s education program, wanted to bring its American art collection to high school students—many from low-income backgrounds in rural parts of Arkansas—unlikely to make a visit in person. “If we’re going to leverage technology, if we’re going to do this with the idea of access for everyone, I think there’s no point in thinking small,” she says.

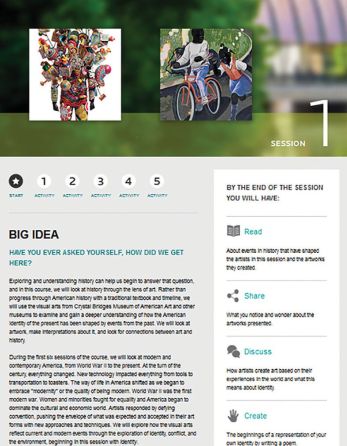

The resulting pilot online course for credit, “Museum Mash-Up: American Identity Through the Arts,” is far different from a video conference or field trip lecture. The course is the right fit for a new state requirement that mandates high school students have .5 credit hours in fine arts and one online course to graduate. About 40 students have taken the course, which was created with technical support from the University of Arkansas.

Kraybill says so far the results have been mixed. “We have something that looks great,” she says. “We have put all of the passion and energy into it, but I do think that we have a lot more work to do to make sure that every student is successful.” Students enrolled from small Arkansas towns like Star City, population 2,248, and Deer, population 680.

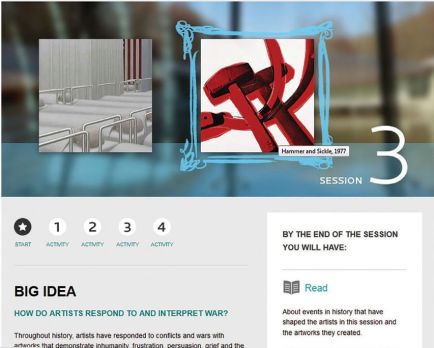

Getting the credit can be challenging. Students must analyze 36 artworks from the Crystal Bridges collection depicted in 3-D rendering, and then curate their own exhibition as a final exam. The course content is wrapped in a video game format inviting students to learn as they play. Pictures can be tagged Facebook style with descriptive phrases like “bold” and “death.”

Each of the 15 sessions, or lectures, explores a “Big Idea” topic. Section 2, for example, is titled, “What does a portrait represent?” The artworks initially offered for analysis are Wayne Thiebaud’s Supine Woman and Norman Rockwell’s Rosie the Riveter. Readings are suggested and online discussion opportunities are provided through Voice Thread, a tool that allows for a crowd-sourced cloud conversation using text, video or audio. It isn’t live interaction, but it’s close.

“We had a lot of kids who did not meet the credit. They were seniors.… If they were not inherently interested, it was a lot easier for them to blow off certain assignments,” says Kraybill. Still, her primary goal is entrepreneurial—to create a tool that teachers can use in preparing online courses. “The way in which they do it is going to depend on whether or not it’s a gimmick or an actual deep learning experience, but they certainly have to take the plunge,” she says.

Even so, won’t socially and politically conservative rural school districts recoil against innovative art courses containing explicit or controversial material? “Our course deals with issues that are challenging, particularly race. We also move into issues of violence, gender, the environment,” wrote Kraybill in an e-mail. “None of the work selected would spark what would typically be considered controversial: basically overt sexuality or nudity. So we haven’t had any issues come up … yet!… What we encourage is the idea that you are allowed to challenge an artist’s intent and the quality of their message. But to do so with evidence to back up your claim.”

While art education online is a new approach for students who must respond to works that are aesthetically abstract and fraught with symbolism, science museums can connect the intangible with the real. The emerging technology of 3-D printing gives students a tool that can turn a set of computerized instructions into a real object.

The George Lucas Educational Foundation promotes that idea through its Edutopia.org website. Some 1 million visitors every month open the portal to learn about innovations that once seemed impossible. One video features a remarkably poised eighth grader named Quin, who has graduated from Lego construction to creating real objects with a 3-D printer. In matter-of-fact narration, Quin explains how he went online to harness “maker” programs that he put into an “Arduino,” or builder, robot. The device instructs the printer to make objects from heated plastic that’s extruded in fine layers like the image slices from a CT scan. As they collect, they form real objects—potentially anything. Quin’s creations include a nightlight and a sign showing his name carved through the plastic. The 3-D printer eliminates most of the physical steps between a concept and the real thing. Quin took his creations and ideas to school, where they were welcomed.

The distance from museum instruction to real-life application is shrinking, thanks to these new tools. “Ultimately, I think that’s what teaching is all about,” says Shree Bose, a Harvard pre-med student whose interest in science was nurtured by the Museum School sponsored by the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History. “That feeling of making a kid’s face light up—when, they’re like, ‘This is really, really cool.’… That moment when a kid understands something … and they realize they have the tools to pursue it no matter what.”

While the new learning technologies are exciting, there are relatively few metrics to define their impact, or indeed which of the new approaches will abide while others fall away. Or whether distance learning will prove so compelling that it will pose an existential challenge to the very institutions that created it—in effect, becoming a digital Frankenstein out of control.

Wayne Clough dismisses such notions as reductionist. “People will always want to see the real thing,” he says, citing the original Star Spangled Banner at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Seeing a digital image of the flag is “not the same thing as being there and seeing that fragile bit of cloth and what it stood for in our history … with 50 other people … all feeling this incredible sense of pride and awe.”

Still, does being a museum require that you are … a museum? The Google Art Project founded in 2011 is a massive online big data compendium featuring works of 11,361 artists from 558 galleries around the world, supported in many cases by detailed explanations and descriptive videos. It’s a meta-museum harnessing metadata, but is it metaphysically a museum experience? Are binary bits of electronic information as powerful as living base pairs of DNA? “Being large and comprehensive doesn’t buy you anything. It’s being good. It’s being truly effective at reaching the people who need what you have,” says Clough.

So what is going to work? There was a lot of buzz at the Fort Worth meeting about the Oculus Rift virtual reality headgear currently in development. Priced at approximately $350, the device has seemingly overcome the challenges of adequate resolution, reasonable cost and low “lag”—meaning that the image doesn’t noticeably blur when you turn your head. It can function as a planetarium on your head showing, for instance, a view of earth from the space shuttle. Our planet’s curvature and blue-white surface is off to your right. Look down and you see the international space station pass beneath your line of vision. Turn left and the earth slowly recedes as you peer out into the void and then at the moon.

The effect is nothing less than stunning—and that could be a problem. “If these experiences are so powerful, … why come to a museum?” asks Doug Roberts, an associate professor at Northwestern University and architect of the WorldWide Telescope Project, sponsored by Microsoft Research, which developed the technology.

Less unsettling are tablet devices like the “Gallery One” in use at the Cleveland Museum of Art. Visitors can take the tablet into a gallery, “show” it to a work of art and receive on-screen answers to questions like, Who painted it? What’s it about? Users can also learn about an artwork’s historical context. For an exhibition about Depression-era painting in New York, for instance, the device could explain what conditions were like during that period.

“Gallery One” is an attempt to integrate the physical, digital and aesthetic dimensions of going to the museum into an organic experience, says John Durant, director of the MIT Museum and a speaker at the Fort Worth conference. “Notice that guests can curate their own experience. You can do your own art show for yourself, and you can download it and take it as a souvenir of your visit,” he says.

How effective are digital learning approaches? They are apparently good enough to alter the perceptions of many patrons about what a museum really is. “The Institute of Museum and Library Services did a comprehensive survey of visitor experiences at museums. And people came back and said, ‘We love the museum’,” says Anthony (Bud) Rock, president and CEO of the Association of Science-Technology Centers, and also a Fort Worth conference presenter. The big surprise: 75 percent of the people who had a great museum experience had not physically visited the actual museum. “I was absolutely stunned by this statistic,” he says. “It tells you what the power is of extending beyond your four walls.”

On the other hand, he says, digital learning can build the actual museum experience. One example is the “Diagnose a Mouse” exhibit on the Nanomedicine Explorer site of the Museum of Science in Boston. The user is challenged to diagnose cancer in a mouse with bits of visual and textual evidence. While that is a virtual experience, Rock believes it’s a motivator. “Most people are saying, ‘Saw your online diagnosis of a mouse, really cool.’ Digital technology driving you to the museum—a great experience,” he says.

The Smithsonian has invested heavily in its “X3D” program to add new dimensions to artifacts like the Gunboat Philadelphia, the only American combat vessel to survive the Revolutionary War. If you were to see the boat at the National Museum of American History, your view would be limited largely to the bow angle. But with 3-D photography, online viewers see what the boat might have looked like originally, or its below-water structure. Likewise, the museum has used 3-D printers to create replicas of life masks made of Abraham Lincoln just after he became president and then four years later—strong visual evidence of the stress of the country’s highest office during the Civil War.

“All the technologies are exciting, and we need to keep track of what’s going on and stay ahead, but it’s all about using the best technology to meet the needs of the audience,” says Kotcho of the American history museum.

Someone has to pay for these efforts, but it shouldn’t be the museum-goer, says the Smithsonian’s Clough. He suggests tapping private donors and foundations like the Gates and MacArthur foundations, which helped bankroll the Smithsonian’s drive to go digital (though it’s not clear how many museums might have that high-level opportunity). While the Smithsonian’s core funding comes from the government, digital development is supported primarily by other sources. “It’s important for museums to control their own destiny,” says Clough.

In his book Best of Both Worlds: Museums, Libraries, and Archives in a Digital Age, Clough writes that museums have had a tough time adapting to the digital environment, partly because of limited technology and “a culture that is built more around curated exhibitions than open access.” Still, Clough says, the message is clear: “Either institutions embrace [digital technology] or they risk being marginalized.”

Perhaps “museum” will ultimately be defined as a verb instead of a noun. It will be a place of engagement at every level—from the building itself, if there is one, to the home office and school. Whatever the medium or the method, a museum should, as its root word suggests, be a muse. Knowledge is the fuel that drives the engine.

So it was with the Wright Brothers in 1903. Their Flyer 1 had a 12-horsepower engine, and their wooden biplane was covered only in cloth. But the design was powered in no small part by the information they received from the Smithsonian.

It’s fair to say that the era of digital technology in American museums has taken flight. Yet like the Wright brothers, we are only at the beginning of the journey. There is no limit to how far and high museums can go, if the basic rules apply. Curate wisdom, disseminate knowledge in whatever appropriate way and be relevant to your audience. Then you can soar.

Jeff Levine is a Maryland-based freelance writer. He was one of CNN’s founding correspondents in 1980. During his nearly 20-year career with the network, he reported from a number of US cities, including Atlanta, and also served as CNN’s Israel bureau chief.