This article originally appeared in the September/October 2015 edition of Museum magazine.

A look back

July 2015 marked the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), a federal law intended to guarantee equal access for people with disabilities to employment, government programs and services, public accommodation, transportation and communications. Many younger museum colleagues may not know a time before the ADA, but baby boomers (born 1940–60) and traditionalists (born 1920–40) will recall that the ADA grew out of a growing disability rights movement that gained momentum after World War II, with disabled veterans advocating for access to employment, housing, education, programs, and services. This movement coincided with and contributed protest and pressure to the period of social consciousness and unrest in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s.

“The most important thing for people to understand is that the ADA is a civil rights law for people with disabilities,” says Beth Ziebarth, director of the Accessibility Program at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. “It came about because people with disabilities in the United States wanted to get rid of outdated stereotypes and to be more fully included in society—whether it was employment, being able to go to the dry cleaners in your neighborhood or going to your local museum.”

The movement was undertaken by a diverse disability community that included people with mobility, hearing, vision and cognitive or developmental disabilities, as well as their families, friends, acquaintances and service organizations (all of which are protected under the ADA). Their collective efforts, not without division and disassociation across the general categories of disability, resulted in important civil rights legislation including the Architectural Barriers Act (1968), Section 504 of the Vocational Rehabilitation Act (1973), the ADA in 1990 and its subsequent amendments and regulations in 2009 and 2011.

The national social consciousness and the ADA prompted significant reflection and action on the part of leaders of museums of all types and sizes who were concerned with how to make facilities, programs, and services accessible to all people. But it went beyond compliance for many. In her preface to The Accessible Museum (American Association of Museums, 1992), Dianne Pilgrim, then director of the Smithsonian Cooper-Hewitt Museum and a wheelchair user for several years due to her diagnosis with multiple sclerosis, wrote: “Just because there’s a ramp to the door or a grab bar in the lavatory doesn’t mean that the problems of accessibility have been solved. Our attitude must change to view the public as just that: a group of diverse people with various needs, concerns, abilities, and limitations.”

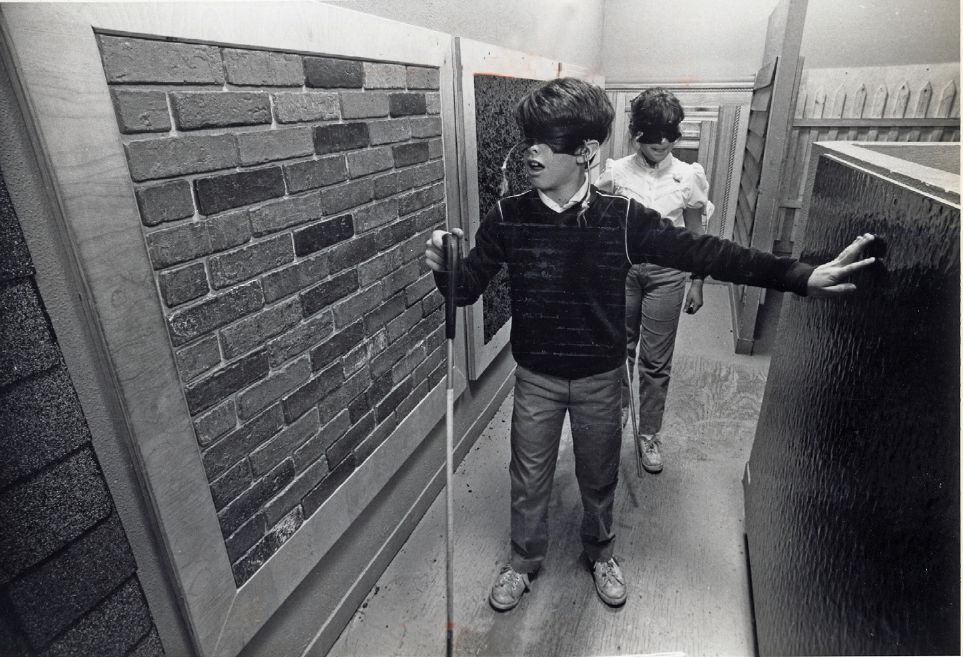

Before the ADA, museums in the United States had varying degrees of experience in accommodating visitors or staff with disabilities. Some museums were ahead of their time. The Boston Children’s Museum, for example, began offering classes for children who were blind or deaf as early as 1916, and opened a landmark exhibit in 1976 called “What If You Couldn’t?” designed to help children and their families better understand the challenges of living with a disability. Institutions in the 1970s and 1980s began responding to the needs of disabled visitors by adding ramps and curb cuts, accessible parking, new signage, large-print versions of handouts or enrichment activities. In 1986, Old Sturbridge Village in Massachusetts established an advisory council comprised of members of the community with disabilities, their advocates and the museum’s staff, with an accessibility coordinator hired to oversee the effort. In 1988, the Bloedel Reserve on Bainbridge Island in Washington printed a common-sense handbook for staff and volunteers on how to communicate with and assist disabled persons. “Speak directly to the person, not the interpreter,” reads one sensitive direction.

Still, as late as the 1980s other well-established museums were not so adaptive to the spirit of inclusive change for disabled visitors and were offering separate “blind tours” and “wheelchair tours.” The call for accessibility and inclusion was not always a swift and universal process.

“When the ADA was passed,” observes Ziebarth, “museums were probably nervous: ‘What does this mean for us? What are we going to do?’ Whether it was a historic house or a large museum—everybody had facility issues that they were taking a look at. It was outlined in the law and people started planning, budgeting for, and implementing the changes necessary. The ADA really made people think.”

The ADA joined with the collective voice of the disability community and the ongoing evolution of standards and best practices in the museum field, Ziebarth believes, creating ongoing positive effects on how we address issues of accessibility and inclusion.

To read more about how museums have evolved since the passage of the ADA to become more accessible—and how they can strive to become yet more inclusive—please see “Museums and ADA@25 – Beth Bienvenu”

Greg Stevens is assistant director for professional development at AAM. He is the co-editor of A Life in Museums: Managing your Museum Career (The AAM Press, 2012).