This article originally appeared in the January/February 2016 issue of the Museum magazine.

We wrote a letter in response to the July/August 2015 issue of this magazine, which focused on themes of social justice. What follows here expands on our views as introduced in that letter.

As museums seek to align with social justice causes, their attention often turns first to external events and local communities. Museums ought to look at issues that exist within their structures in addition to joining the fight for social justice outside their walls. Our objective isn’t to dissuade museums from aligning with social justice endeavors, but rather to expand the conversation to include internal practices and institutional legacies that prevent us from doing our best work.

Why is it important that museums turn the social justice lens inward? A lack of introspection and visible internal change projects the idea that museums have something special others lack—that they are the “chosen” group to help those that cannot help themselves. There are some clear problems with this line of thinking. First, it assumes an exceptionalism that distances museums from other organizations and institutions trying to address social justice. Second, it obscures the fact that museums have many of their own issues to deal with. Museums can be strong partners toward positive social change, but this effort ought to be accompanied by critical self-examination.

In particular, we call on museums to evaluate three key topics: institutional legacies, staffing and language. These deeply interrelated issues represent recurrent themes in ongoing conversations with our friends and Incluseum collaborators.

The Incluseum is a project and blog we co-founded in 2012 to encourage critical discourse and reflective practice regarding inclusion in museums. At the time, no such outlet existed, and we found it difficult to locate others who were thinking about and conducting related work. It dawned on us that this opacity and lack of connection would continue to slow true progress, so we decided to launch the Incluseum blog as a multi-voice platform where museum practitioners and scholars could share their ideas and discoveries. We see the multi-voice model as key to inclusive work. Rather than centering on our limited perspectives, the Incluseum blog invites authors to represent themselves and contribute to a collection of viewpoints. We’re convinced that this bridging of people, examples, and ideas helps increase the visibility of inclusion-related work, which is crucial to building momentum for lasting change.

In addition to the blog, we have brought people together offline through events and workshops and experimented with what we believe are “next practices” (an extension of “best practices”) for inclusion-related work in museums. These experiments have resulted in collaborative digital and analogue exhibits, among other outcomes. In short, the Incluseum is the ongoing product of many entangled collaborations, reflecting current practices and scholarship and creating a vision for what a radically inclusive museum can look like.

1. Institutional Legacies

“We want to work with communities, but how do we get started?” “When we reached out, we were met with suspicion.” “It takes a long time to build trust!” “How do we sustain relationships?”

“We want to work with communities, but how do we get started?” “When we reached out, we were met with suspicion.” “It takes a long time to build trust!” “How do we sustain relationships?”

Through our work with the Incluseum, we have frequently heard these observations and questions. In reality, though, every museum has been part of a larger network of relationships with community groups, funders, collectors and so on since its founding. In other words, each museum has an institutional legacy that needs to be reckoned with to better understand its present-day challenges in working with communities.

Questions that can help probe this legacy include: Who are my museum founders? Where did their money come from? Where did the collections come from; were they looted or forcibly removed from source communities? What does my museum not have in its collections and why? Did my museum practice active exclusion during, for example, the Jim Crow era? How else has my museum maintained practices over the years that reinforce service to some groups over others? Today, who are the authors of the stories that my museum tells?

While considering and seeking answers to these questions might be an uncomfortable task, it is a necessary place to start. Consider, for example, a museum that, under Jim Crow laws, restricted or prohibited African Americans from visiting. A few decades later, it is not surprising that this museum would see few African Americans walking through its doors and would have difficulty establishing and sustaining relationships with those who, a few generations prior, were actively excluded.

Museums’ desires to form inclusive relationships with their communities cannot be disassociated from the relationships they had in the past. Even if that history predates everyone on staff, we must educate ourselves and make amends for them today. Legacies based on systems of power and oppression will not go away simply by ignoring them. Dealing with them allows us to get to the heart of who our museums are for—determining for whom (and by whom) our cultural institutions are designed and, by extension, whose experiences are acknowledged by museums and whose are not.

2. Staffing

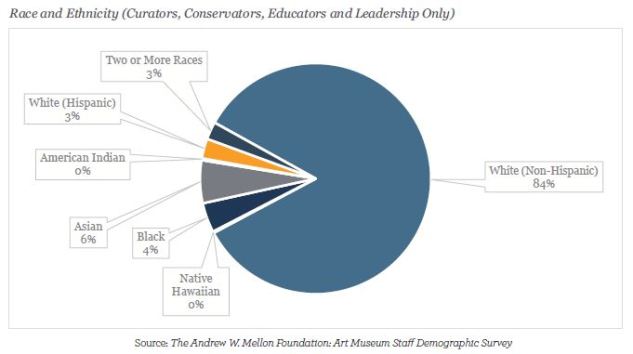

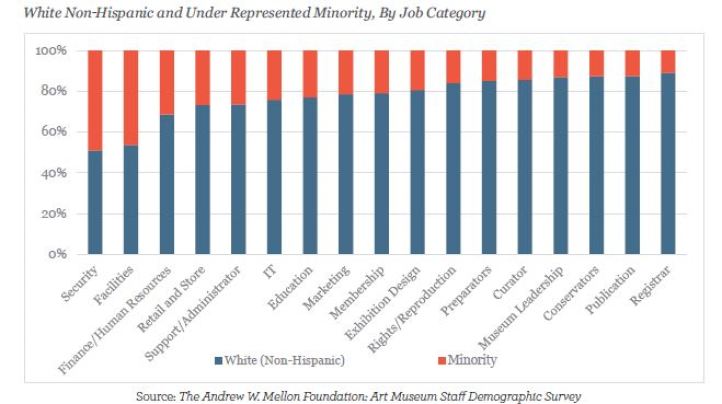

Deeply connected to the question of “Who are museums for?” is “Who works in museums?” This question also arises when we turn the social justice lens inward, and it links to a growing realization, as affirmed by recent research, that the field lacks diversity. In its 2015 survey of art museum staff demographics, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation found that women made up 60 percent and non-Hispanic whites constituted 72 percent of the art museum task force. The overrepresentation of non-Hispanic whites might not seem problematic since this group currently makes up 62 percent of the total United States population. The Mellon Foundation found, however, that “there is significant variation in demographic diversity across different types of museum employment. Non-Hispanic white staff continue to dominate the job categories most closely associated with the intellectual and educational mission of museums, including those of curators, conservators, educators, and leadership.”

This lack of diversity in sections of our organizational charts is often ascribed to a broken pipeline to museum employment. Based on this assessment, strategies have been developed to help those not currently represented to acquire the qualifications for museum work. For example, in 2014, the Mellon Foundation developed a paid fellowship program in partnership with five major art museums to help prepare undergraduate students from traditionally underrepresented groups for curatorial careers.

As we recently discussed on the Incluseum blog (in collaboration with Joseph Gonzales, Nicole Ivy, and Porchia Moore), initiatives aimed at “fixing” the pipeline do little to restructure the work itself, change the requisite qualifications or shift the institutional culture. Such initiatives will fall short if the workplace culture that new employees find after getting through the pipeline is set up to tokenize them or undervalue their contributions. So, let’s broadly question the practices that are implicitly favored by museums’ current employment arrangements. They are upheld by expectations that candidates with high levels of academic achievement and institutional references should accept low-wage positions and that they should adjust their needs according to the existing workplace culture. As part of this critical self-assessment, let’s also ponder the role of intersecting privileges, such as race and class, in determining who works and studies in the field.

3. Language

We are at an exciting moment in the museum field, in which a host of individuals are interrogating how commonly used words reinforce exclusion or distract us from its root causes. Terms such as social justice, inclusion, diversity, access, equality, social value and community have become ubiquitous, yet they might be narrowly understood or highly coded—that is, they may take on meanings based on implied associations. These words also have positive connotations; every museum wants to deliver social value and provide access to the community, right? However, when the implicit meanings of these words go unaddressed, we lose chances to explore challenges and make

strategic changes. For example, casual use of the term community can fail to clarify who is or is not represented by that label and why.

Our collaborator Porchia Moore has written and spoken extensively on words and their meanings, drawing attention to the coded way community is used to refer to black and brown people. As Moore demonstrated in her Incluseum article “R-E-S-P-E-C-T! Church Ladies, Magical Negroes, and Model Minorities: Understanding Inclusion from Community to Communities,” this pattern silently plays into respectability politics, wherein only some communities, those perceived to be approachable and accessible, are sought out to speak on behalf of the entire group. Are museums subconsciously seeking to work with communities and individuals that they believe will not disrupt or transform them? With a closer look at the use of the term community, some of the implied biases could become clearer and, as a result, challenged.

Our use of words and how they inhibit inclusion is also being explored by those thinking critically about the corporate and public sectors. In a recent New York Times article, “Has ‘Diversity’ Lost its Meaning,” Sally Kohn began:

How does a word become so muddled that it loses much of its meaning? How does it go from communicating something idealistic to something cynical and suspect? If that word is ‘‘diversity,’’ the answer is: through a combination of overuse, imprecision, inertia and self-serving intentions.

In her piece, Kohn highlighted the large disparity between the progress that leaders, companies, and institutions claim they want and what they actually do about it. She applied to her discussion the work of Nancy Leong of the University of Denver, who coined the term racial capitalism, defining it as an individual or group deriving value from the racial identity of another. In museums, as in other sectors, deploying the word diversity can confer moral credibility. It also is often discussed as crucial for institutional survival in a deeply shifting demographic landscape. In these two examples, the institution is situated as the primary (or only) beneficiary of diversity discourses, which feeds into the logic of racial capitalism. And when these benefits come to institutions that do little to actually address their part in ongoing inequities experienced by people of color, it is no surprise that museums may meet reproach when they reach out to work with these communities.

Likewise, integrating words such as community or inclusion into mission statements or strategic plans can benefit museums, but may mean little and possibly add insult to injury to historically excluded groups if museums do not open up to deeply felt change. Tools such as Margaret Middleton’s Family-Inclusive Language chart (see opposite page) and our Incluseum Taboo cards (page 41) are just two resources museums can use to scrutinize their words and get to the core of what they mean to express.

Conclusion

Our goal is to leverage this moment of increasing interest in diversity and inclusion to ensure that it is more than superficial buzz. We must address the realities that will keep plaguing us if left unacknowledged. Whether through policy leadership, grassroots movements, centralized resources or practice-focused tools, the way forward must encompass all three issues discussed above. We have stayed away from providing how-to formulas because we believe that each museum is unique and must find its own way to address institutional legacies, employment practices and use of language. That said, the Incluseum blog will continue to feature the exceptional inclusion related work of practitioners and scholars to inspire others in the field and serve as examples of next practices.

Download the Family Inclusive Language chart.

RESOURCES

On Historical Legacies and Oppression:

- Lonetree, Amy. Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums. North

Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2012. - Mears, Helen, and Wayne Modest. “Museums, African Collections and Social Justice.” In Museums, Equality

and Social Justice, edited by Richard Sandell and Eithne Nightingale. Routledge Publishing, 2012. - trivedi, nikhil. “Oppression Museum Primer.” Incluseum (blog). 2015. http://bit.ly/1bDG6V7

- trivedi, nikhil. “The Text of My Ignite Talk at MCN 2015.” Nikhil (blog). 2015. http://bit.ly/1PmYbZz

On Staffing: - Gonzales, Joseph, Nicole Ivy, Porchia Moore, Rose Paquet Kinsley and Aletheia Wittman. “Michelle Obama,

‘Activism,’ and Museum Employment Part III.” Incluseum (blog). 2015. http://bit.ly/1M49SAv

On Language: - Kohn, Sally. “Has ‘Diversity’ Lost its Meaning.” New York Times. October 27, 2015. http://nyti.ms/1RLFfl3

- Moore, Porchia. “R-E-S-P-E-C-T! Church Ladies, Magical Negroes, and Model Minorities: Understanding

Inclusion from Community to Communities.” Incluseum (blog). 2015. http://bit.ly/1MUAYO4 - Moore, Porchia, Rose Paquet Kinsley and Aletheia Wittman. “Michelle Obama, “Activism,” and Museum

Employment, Parts I and II.” Incluseum (blog). 2015. http://bit.ly/1iRKvXW and http://bit.ly/1SG6yOe

Rose Paquet Kinsley and Aletheia Wittman are based in Seattle. In addition to coordinating the Incluseum, they consult and advise nonprofit organizations on inclusion-related work. You can reach them at incluseum@gmail.com. Alyssa Greenberg, Margaret Middleton, Porchia Moore, Adrienne Russell, Chris Taylor and nikhil trivedi contributed to the thinking that went into this article.