This article originally appeared in the July/August 2016 issue of Museum magazine.

Envisioning museums as part of an intellectual and professional community that crosses international borders.

In recent years, the impact of outside conflict on museums has captured the attention of our profession. Museums in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Mali, Libya, Tunisia, Egypt, Ukraine, Georgia, and Yemen—to name only a few—have found their collections under attack in the past two decades. We appear to have entered a period in which cultural heritage is being deliberately targeted.

As professionals in the field, we have an ethical commitment to the idea that museums are responsible for curating the past for future generations. That mission is imperiled when belligerents seek to erase the physical evidence of a people from history. How do museums safeguard their collections and their staffs in these situations? Moreover, what can major organizations such as AAM and ICOM do to assist our colleagues?

History of Supporting Museums in Conflict

Much of what we know about safeguarding museums in times of conflict comes from experiences during World War II. Based on reports from cities across Europe (as well as some homegrown experimentation), curators and conservators prepared guidebooks on topics such as how to pack and move collections in an emergency and how to stack sandbags and bricks for maximum protection against blasts. These handbooks formed the foundational knowledge for emergency response and went into immediate use by museum professionals.

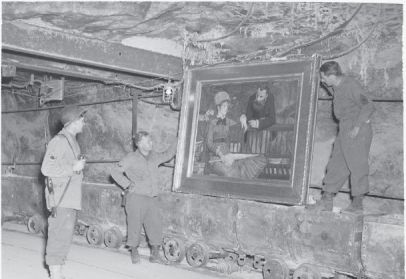

Across Europe, museums moved their collections out of historic urban centers to rural communities, using caves and mines to house famous artworks and scientific specimens. In the United States, fears that Washington, DC, would be aerially bombarded led to the evacuation of the most important collections from the National Gallery of Art to the Biltmore mansion in North Carolina, the Library of Congress to Fort Knox in Kentucky, and the Smithsonian Institution to Shenandoah National Park. Museum professionals also advocated for the creation of monuments, fine arts, and archives teams within the Allied forces, which are now immortalized in popular culture as the Monuments Men or the Venus Fixers. Serving as members of military units, these curators, professors, and cultural leaders worked to protect important sites damaged on the front lines and ultimately took on the daunting task of identifying and returning Nazi-looted artworks, libraries and other collections to their countries of origin.

Instituting Postwar Protections

Following World War II, international protocols were put in place to prevent the looting and destruction of cultural property in future wars. The 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, more commonly known as the 1954 Hague Convention, aimed to address many of the problems that museum professionals experienced during World War II. The convention forbid targeting cultural sites except in cases of military necessity, prohibited armies from looting cultural property, and ensured that object collections could be safely kept or moved out of harm’s way.

As a law-of-war treaty with 127 current state parties, the 1954 Hague Convention is designed to govern the conduct of state actors. In recent years, cultural property destruction has been conducted by non-state actors and other entities that are not recognized as legitimate governments by the international community of nations. As a result, we can no longer rely on an international legal convention to restrain the destruction of heritage in a conflict. While the 1954 Hague Convention provides a legal benchmark and an aspiration for the museum field, protecting museums requires much more engagement with the professionals who are in a position to act during a conflict.

The 1954 Hague Convention was not the only post-World War II innovation in cultural heritage protection. The need to rebuild Europe and to preserve the historic character of its cultural landscape led to advances in conservation science and to the development of an international infrastructure to maintain this work. The International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property (ICCROM) developed and institutionalized the knowledge gained from postwar conservation. Today, ICCROM continues these efforts through the First Aid for Cultural Heritage in Crisis course, which offers hands-on training for emergency response and recovery of collections.

Other major international organizations have launched complementary efforts. The International Council on Monuments and Sites’ International Committee on Risk Preparedness (ICOMOSICORP) addresses site-based emergency conservation and is a frequent collaborator in ICCROM’s training programs. In 2004, the International Council of Museums (ICOM) launched the Disaster Relief Task Force (recently renamed the Disaster Risk Management Committee, ICOM-DRMC) following the Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami. Composed of ICOM members with disaster response experience as well as key members of ICOM’s governance and secretariat, the ICOM-DRMC maintains the Museum Watch List, which tracks damage to cultural institutions and assists in disaster response programming.

Realities of Conflict Today

Nonetheless, when a conflict occurs, it is primarily up to local heritage professionals to act. Every recent instance of collections preservation—when there was not an occupying military power involved—relied upon local efforts. The challenge for the international museum community is how to support these initiatives. The problem is not one of expertise; our colleagues in conflict-affected areas are often very well trained. Rather, the issue is one of developing logistics and gathering financial resources to support a series of practical interventions.

During a conflict, there are frequently public calls to move museum collections to so-called “safe havens” in order to protect the objects. There are situations when it is appropriate and necessary to move museum collections out of harm’s way. The United States held a Magna Carta for the United Kingdom at Fort Knox during World War II, for example. Similarly, during the Afghanistan civil war in the 1990s, the Afghanistan Museum-in-Exile was established in Bern, Switzerland, to house collections from the country until they safely could be returned. The 2012 evacuation, conducted under the cover of night, of historic manuscript collections from Timbuktu’s libraries to Bamako, Mali, is considered a recent success—particularly after extremists burned some remaining manuscript collections when Malian and French military forces retook the city.

Yet, risks come with evacuating museums. Moving a collection may expose it to fragmentation and theft in a conflict zone. Care must be taken that the good intentions of moving material to a “safe haven” do not increase illicit trafficking of those kinds of objects. Basic attention must also be given to packing objects for a move, even when in haste. An ill-advised packing job resulted in tar leaking onto George Washington’s uniform during the Smithsonian’s World War II evacuation. More recently, humid conditions in Bamako have exposed Timbuktu’s manuscripts to the risk of material degradation while discussions over their return continue.

When collections cannot or should not be moved, it is still possible to take basic precautions. Using sandbags or bricks to reinforce the structural resilience of museum buildings is an important step when conflict is anticipated. Fortifications can help protect museum structures from damage and act as a deterrent to theft. False walls and floors also have been used to secure collections during the civil wars in Afghanistan, Beirut, and Syria. These efforts are the result of dedicated local heritage professionals taking action and placing themselves at great personal risk.

How We Can Help

The international community can offer assistance even in these circumstances. Acting together, the University of Pennsylvania Museum, Smithsonian Institution, and ICOM-DRMC supported the curatorial and conservation staff of the Ma’arra Mosaic Museum in their efforts to protect the mosaic collection as part of the Safeguarding the Heritage of Syria and Iraq (SHOSI) Project. After consultations between the Syrian museum’s staff and international conservation experts, in winter 2014, the mosaic collections were covered with a water-soluble glue and flash-spun polyurethane fabric. The staff then built a stabilizing sandbag barrier along the mosaics and gallery walls. This low cost project, supported financially by the J.M. Kaplan Fund and Sotheby’s and logistically by the international community, resulted in the collection’s preservation. In June 2015, the museum was hit by a barrel bomb dropped by the Syrian Air Force. The stacked sandbags seem to have diffused the full force of the bomb, and the mosaic collections survived largely intact.

Contemporary conflicts do not have clear start and end dates. The strategies that combatants pursue during civil wars, ethno-nationalist and sectarian conflicts, and hybrid warfare can result in periods of prolonged instability for museum caretakers and the communities that they serve. As a result, it will not always be clear when a conflict has ceased and a “normal” state of museum operations can return. Even seemingly stable environments can be upended. The Iraqi Institute for the Conservation of Antiquities and Heritage in Erbil had been conducting a skills-building course for Iraqi heritage professionals when the ISIS advance on Mosul cut short the program in 2014. A sudden and unexpected need emerged for emergency preparedness training and project implementation in Iraq. Training courses now include expanded sessions on disaster risk management for collections and sites.

A perpetual challenge identifying what might be the next conflict zone in areas of political instability. Following the liberation of Timbuktu, the Ministry of Culture of Mali, National Museum of Mali, UNESCO, Smithsonian Institution, ICOM-DRMC, and French Ministry of Culture convened a meeting for museum representatives from eight West African countries. The group discussed the risks that their institutions face, as well as their importance as sites of community resilience in the face of conflict.

Perhaps the greatest unaddressed challenge in protecting museums during a conflict is supporting curators, conservators, and other staff members if they are forced to flee. Not only do we owe it to our colleagues to develop an international system through which they can move to safety if their lives are at risk, but we recognize that when collections and sites are destroyed, the caretakers’ collective memory becomes part of the record of that heritage. Currently, the museum community lacks the ability to help our colleagues. Our international system of protecting scholars in conflict zones dates to World War II and prioritizes academics with a doctoral degree. Many museum professionals have master’s degrees or advanced training, but because they don’t have doctorates they do not qualify for the Institute of International Education’s Scholar Rescue Fund and the Scholars at Risk Program under ordinary circumstances.

In other fields, new organizations have stepped in, recognizing a special responsibility to assist colleagues who are in harm’s way because of their professional activities. Lawyers Without Borders, the Committee to Protect Journalists, the Committee of Concerned Scientists, and Physicians for Human Rights are prominent examples. The museum community needs to address this serious gap. ISIS’s execution of Khaled Al-Assad, the former director of the World Heritage Site of Palmyra, and the death of Anas Radwan, founder of the Syrian Association for the Preservation of Archaeology and Heritage, from a barrel bomb while he was documenting damage to the World Heritage Site of Aleppo remind us that heritage professionals are at considerable risk. We must find a way to do much more.

Securing Support for the Future

Undertaking training programs, collections evacuation, post-conflict programming, and scholar rescue efforts requires financial support. Although many high-impact interventions are low cost, in an era of beleaguered museum budgets, it can be difficult to imagine donors funding emergency programs that take place far beyond their hometown museum’s walls. Making a case for having a stable pool of funding for emergency training, response, and recovery is challenging. But the lengthy application process required to fund emergency interventions is an obvious problem. Conflict events are unpredictable and do not follow typical grant cycles.

The Prince Claus Fund for Culture and Development is one of the few international philanthropic organizations that has devoted significant financial resources to this area. It is now joined by the J.M. Kaplan Fund, which has long supported archaeological site conservation in the eastern Mediterranean. The National Endowment for the Humanities is also looking to support emergency preservation initiatives through special programming. Together, these efforts represent a hopeful trend, suggesting that the philanthropic and museum communities can unite to develop a new framework for assisting museums during conflict.

Even as the news of heritage destruction is grim, museums are beginning to envision themselves as part of an intellectual and professional community that crosses international borders. If we are able to sustain and build upon this goodwill and translate it into action, there is reason to be optimistic. But it involves making an institutional commitment to the idea that the work of a museum extends throughout the world. It means being concerned not only about museums in St. Paul and Philadelphia but in Kiev and Beirut. Indeed, the future of museums and our colleagues in many regions of the world may depend on it.

Brian I. Daniels is director of research and programs, Penn Cultural Heritage Center, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Philadelphia. Corine Wegener is cultural heritage preservation officer for the Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative, Washington, DC, and chair of ICOM-DRMC.