This article originally appeared in the November/December 2017 issue of the Museum magazine.

My talk today is a reflection on where we’ve been and where we are today. It shares my vision for tomorrow as well, in which a coalition of museums and museum professionals work together to embrace the next horizon of challenges facing our field.

Likely many of you expected this keynote to focus on technology. We love the latest thing, the shiny new object, headlines that speak of such advances. It’s easy to fixate on technology, but too often, when we do so, we miss the important underlying forces driving change—what people want and need, how they interact with one another. There was a Sunday morning cartoon from the 1960s called The Jetsons; it envisioned a future of flying cars and robot maids. We have both those things now. We also have gender equity in the workplace and a world of distributed, self-directed learning. In the Jetsons’ universe, mother Jane stayed home to “keep house” while little Elroy went off to school each day. The writers predicted the technology, but they were oblivious to the bigger, more important cultural changes we would experience.

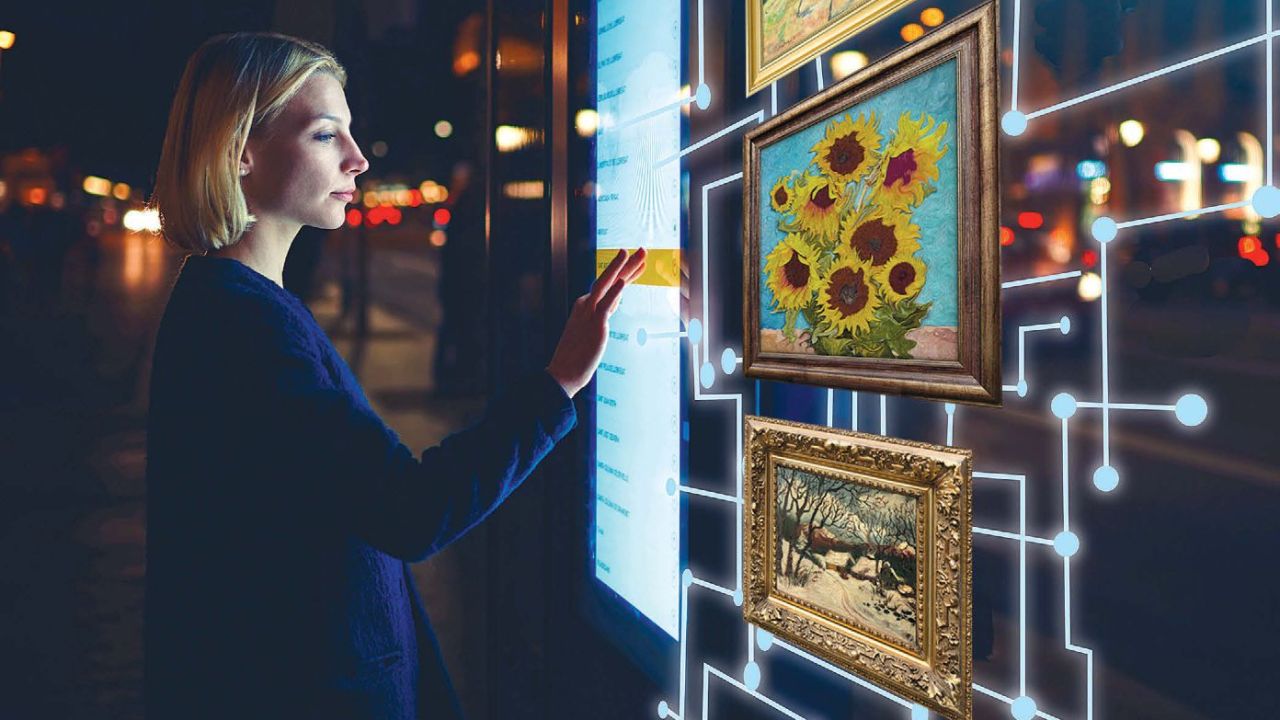

Similarly, at the turn of the 20th century, museum people often focused on technology when they thought about the future. And it’s true that some technologies, notably digitization, digital fabrication, and virtual and augmented reality, have had a significant impact on our practice. In the 2020s, what we now call the “Digital Push” led to the proliferation of museums that exhibited only reproductions, either virtual recreations based on digital scans or physical objects created by digital fabrication. But to me, the most interesting thing about the Push is how it transformed museum culture. For example, art museums began exploring new and alternative venues for exhibitions of various sizes. No space was deemed unworthy, and collections, both digitally produced and real, found new venues. Train stations, bus stops, senior housing, elementary schools, supermarkets, clothing stores, and sidewalks all became exhibition spaces. Artworks that had been unimaginable to lend, too delicate to display or transport, now through technology could be included in exhibitions the world over. The Digital Push helped pave the way for museums to shift their narratives from big names and topics to personal stories and community histories.

Even as museum exhibitions became more distributed throughout the world, the very concept of “museum” was changing—from single-purpose organizations housed in iconic architecture to hybrid institutions that also fill the roles that used to be siloed in libraries, community centers, and schools. Many museums are now open 24 hours a day; others are the major source of education and social resources for children and seniors in their communities. Museums are now libraries, libraries are now schools, and teachers are now museum administrators. Community organizers run museum programs, and museum staff operate learning laboratories and teach classes in science, art, and the humanities. Often, these new museums arose to fill community needs when traditional institutions struggled and failed. Each new hybrid museum represents a community that was spared from losing a library, preschool, park, house of worship, health center, and other valuable, community-dependent organizations and facilities.

How did this happen? How did we go from a static concept of “stuff in a building open 10–5 Tuesday through Sunday” to the fluid, dynamic, community-centered institutions of today? The modern museum evolved out of financial necessity and the realization that our offerings, at the turn of the century, were no longer relevant and of benefit to society. We had become unsustainable mausoleums, with dated business and programmatic models. We let our history constrain our vision, clinging to a business-as-usual approach regardless of whether the public cared or came. We found ourselves closed off from the world in many respects, standing idly by as our industry languished.

To survive, some museums merged; others went out of business— selling their collections or giving them to other institutions. Even as some small to midsize institutions closed, many large founder-funded institutions opened, along with private for-profit museums and thematic museums, competing for donors, audiences, and media attention. The overall picture was bleak. By 2025, museum attendance had reached historic lows, and close to 10 percent of museums that existed in 2000 had closed their doors.

But museums rallied, challenging our old paradigms and letting ourselves be guided by the needs of our communities. Out of the darkness, a new type of museum emerged, one that no longer looked inward to a self-serving mission or offering one-sided “community partnerships.” We became open and accessible, revolutionary in our thinking and our operations. Museums reinvented themselves as civic spaces, embracing social responsibilities; we became institutions whose purpose was to change the world.

Some of the most successful new museums of this century are those that focus on changing the world in specific ways: museums dedicated to combating climate change, rising sea levels, deforestation, and violence; reducing homelessness; promoting enlightened immigration policies; and fostering their communities’ health and well-being. In some instances, museums have shored up failing civic infrastructure. When health and social service organizations began to struggle in the face of rising rents and dwindling government funding, many museums reached out to provide space and programmatic support. Eventually, some museums folded these social services into their mission —in doing so, better serving their purpose and becoming truly essential civic institutions. These institutions provided a valuable lesson for all of us, showing that museums can be flexible in facility, structure, and programming while remaining true to their museum nature.

Meditation room at the Saint George Museum of Art, Utah.

Often, these new museums arose to fill community needs when traditional institutions struggled and failed. Each new hybrid museum represents a community that was spared from losing a library, preschool, park, house of worship, health center, and other valuable, community-dependent organizations and facilities.

To reinvigorate our sector, some museums looked to libraries for inspiration. Looking back, we can see how libraries built on a long tradition of doing more than lending books. In the early 21st century, they stepped up to meet the needs of their communities by lending tools, seeds, even plots of land to grow vegetables; providing training and access to computers; and focusing on community-oriented thinking. Libraries pioneered the practice of hiring staff dedicated to serving the homeless and connecting people with social services—now such staff are common, if not expected, in museums as well. And even as libraries decreased their emphasis on lending books, museums ramped up their focus on lending objects—a practice whose history dates back to early university museums that lent art collections to students and faculty. It has become a given for museums to operate maker spaces and digital fabrication labs, enabling audiences to digitally print and manipulate the data of our collections. In time, museums began to experiment with lending their staff; and eventually, through artificial intelligence and virtual reality, we were partnered with our audiences around information sharing and learning.

Lunch at the Community Health Center at the Museum of Art and History in Utica, New York

Some museums have taken on functions once relegated to houses of worship, becoming places of faith, spirituality, and reflection. Museums with specialized religious collections often incorporate chapels, meditation rooms, or other dedicated spaces for religious practice. This role evolved in part due to the number of houses of worship that closed in the first decades of the century, stressed by rising operating costs, dwindling memberships, and changing audience demographics. Due to these constraints, synagogues, mosques, and churches usually share sanctuary, education, and community spaces with other religious communities. Where a community once housed three or more separate faith-based organizations, they often now house one. Often, these organizations also function as community museums, housing art and history collections; collecting the oral histories, photographs, and keepsakes of their communities; and running outreach, health, and social service programs. These new spiritually based museums run schools and adult daycares and employ chaplains and theologians. They provide a new form of community space and give rise to some of the most interesting exhibitions and related programs happening now in our sector. So, this is another fertile area of hybrid practice.

The Dawkins Center at the Museum of Science in Naperville, Illinois, combines a preschool enrichment program with eldercare services.

The ways in which our field has responded to the challenges of the 21st century have led society to see us as linchpins in our collective ability to meet the future head-on. However, assuming this position of leadership involved sacrifice. We saw longstanding positions that were symbols of our field change, evolve when possible, and dissipate when not. The word “curator” once meant a person responsible for collecting, organizing, and presenting objects. Now, it signifies a person who is responsible for helping people access museum resources in order to fill their needs. A curator today is in many ways akin to a 20th-century librarian.

Artificial intelligence in its myriad of forms has supplemented our work, taking on automatable tasks while enabling humans to focus on human skills. As museum security came to rely more on technology, guards spent more of their time acting as ambassadors, over time becoming our gallery and community liaisons, providing assistance and troubleshooting when necessary. The transition from museum guard to museum facilitator was driven by the fact that our museums needed more staff out in our public spaces—yes, for the safety of our objects, but more importantly, for the safety and engagement of our public. Today’s museum facilitators employ empathy and social intelligence to assist the modern-day museumgoer.

As we changed our staffing models to accommodate the influx of visitors, expanded usages of our facilities and online resources, and the other ever-growing demands on our museums, we saw a hiring boom in the areas of technology, audience experience and engagement, and marketing and communications. As museums moved away from a scholarly focus to a community one, from academic to popular, from selective to inclusive, we rebuilt our staffing strategies around ways to engage our communities. We hired social workers and counselors, therapists and psychologists, artists and musicians, engineers and web developers. We hired storytellers and clergy. We hired with the intent of fostering an engaged public and creating modern, contemporary institutions. Now, in addition to museum educators, we have personal learning mentors who help young people match their passions to the resources in their communities. And much of our work, from design to research, is distributed—drawing on the expertise of amateur and professional experts around the globe.

The Minneapolis Museum of Art and Culture provides worship spaces for six local congregations of various faiths. This shrine is maintained by the local Buddhist community.

Museum have long functioned as third places—social centers of our communities. This role expanded in the early 21st century as museums adjusted rules and policies, expanded hours of operation, and rearranged their spaces. First floors that were once reserved for admissions, stores, and high-profile galleries were redesigned as flexible, adaptive public spaces, filled with seating and tables, books, food and drink, computers, and other tools of the digital age. Our public came to treat these new spaces as indoor extensions of our public parks. Museums rethought their land as well and now steward a significant fraction of the public green space in our crowded cities. Museums as community resources have become even more important as levels of employment, and the average workweek, have decreased. People have more free time on their hands, and museums have become valued community spaces in which to socialize as well as learn.

Even museums that continue to hew more closely to the traditional format have changed in significant ways. Many art museums shifted, for example, from a national and international focus to one that is local and regional as their institutions became entwined with organizations and members of their communities. Exhibitions now tell the active stories of what’s happening in their communities, often created entirely by the public with support from institutions. Museums embrace relationships over projects, truly giving over spaces to community artists and activists. Removing stipulations and limitations, allowing for these exchanges of ideas, activities, and stories to take place in evolving installations over months, not days, in effect creates community residencies.

Technology provided us new ways to realize our dreams, yet it was the public, through how they chose to spend their time, attention, and money, that had the biggest impact on our organizations. Institutions today are no longer obsessed with bigger, newer buildings and ever-expanding collections. They’ve moved on, placing more value on creating better, smarter, more community oriented facilities and resources. These efforts are paying off. Attendance has steadily increased over the past two decades, with upward of 80 percent of Americans visiting a museum, physically or virtually, three or more times a week. Our institutions report record attendance—but over the past few years, we are starting to see institutions that don’t even bother to measure attendance, recognizing it as a shallow proxy for what really matters. Our boards, supporters, and funders know that the most important measure of success is the impact that museums have on the health, happiness, and engagement of our communities.

Yet there is an even more crucial role that museums can play in helping their communities navigate the current challenges of work: unemployment, underemployment, part-time labor with no benefits, and rapid changes in the workforce. Much of today’s work and tomorrow’s is being invented in real time, and the need for continual job training has become paramount. Today and in the future, I see museums playing a critical role as what I am calling “fourth places,” where people come to work, learn, and teach each other. In an era when higher education has become unaffordable and impractical for many, museums can serve as sources of continuing education. When self-employment and entrepreneurship are the best roads to economic mobility, museums can serve as incubators for new businesses. A widely cited report has forecast that 20 percent of the jobs that will exist in 2060 haven’t been invented yet. Museums can empower people to anticipate, even invent these new roles.

Laray Birch, first poet-in-residence at the Los Angeles Metropolis Museum of Art and Culture, leading a poetry slam workshop in 2032.

As we look ahead, we see plans for museums in outer space and at the bottom of our oceans. One day, we will visit museums on Mars and other reaches of our known universe. But never forget that the biggest, most important innovations we can make are right here in our own institutions—in how we define the purpose of our organizations, the missions that we create to accomplish our purpose, and how we measure success. Having seen how far we have come in the past few decades, I have every confidence museums will continue to reinvent themselves to meet the challenges of the future. Thank you.

Adam Rozan is director of The Museum, a collection of physical objects used to engage artists and innovators in preparation for the 22nd century.