One hundred and thirty-three years after the Statue of Liberty first arrived in New York harbor, to the day, my husband and I took our daughter to the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island on Father’s Day. Our almost-six-year-old has been obsessed with the Statue for months. I guess it’s in her blood.

Back in the mid-1980s, as the two-year conservation and renovation of Lady Liberty put her in the news, I dressed as the Statue of Liberty for Halloween, donning a green sheet, a homemade crown, and a flashlight torch. Decades later, my daughter is studying up, determined to do the same.

During our visit to Liberty Island, I was determined to teach my daughter about the significance of the monument and the important history of Ellis Island. I was inspired to re-immerse myself in the spirit of these places as symbols of American values of freedom, democracy, and justice. And I wanted to, together, read the plaque with Emma Lazarus’ now-famous 1883 sonnet, New Colossus, ending with:

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

As so many things are these days, our visit was a more emotionally-fraught and complex experience than I expected. Reading and trying to explain those words against the backdrop of news about children being separated from their parents at the border—as a deterrent to other immigrants and as a political bargaining tool—reignited my personal fury.

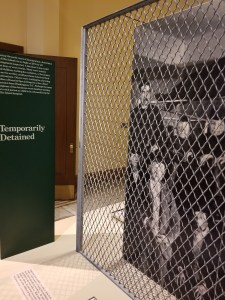

Regardless of where one stands politically on the many complicated issues surrounding immigration, it’s hard to reconcile the recent news with America’s values. News of forcefully separating families, images of “detention camps,” and stories of abuse while in custody raise our collective conscience. These abhorrent depictions from the border are impossible to ignore.

All the while, some public officials continue to use dehumanizing language about refugees from all over the world, and government agencies deliberately intimidate immigrants across the country. There’s talk of adding a citizenship question to the Census, and even reports of border patrol officers stopping visitors outside museums close to the Southern border to ask for identification.

For me and many Alliance members, it all raises questions about our collective values and the ideals on which our ancestors, most of whom were immigrants, built our communities. And, for us in the museum field, it raises questions about museums’ roles.

Dealing with hundreds of years of immigration challenges and controversies in our country is not a new issue for American museums. Not only have museums shared stories about the history of immigration, many have served as beacons of light and support for those seeking to become citizens of our country.

The New-York Historical Society’s “The Citizenship Project: Discovering American History through Art,” helps immigrants learn American history they need to know to pass the grueling United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Naturalization Test through images, sculptures and stories that make the information more meaningful than simply memorizing pamphlets of facts.

Museums are frequent hosts of joyful citizenship ceremonies, such as the recent Flag Day ceremony at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Museums across the country support immigrants and new Americans in countless ways – language and cultural literacy programs, skills training, and even transportation for families with a recently deported parent. Those museums along our southern border, such as the Children’s Museum of Brownsville, often play a special role, even welcoming unaccompanied children living in immigrant detention centers.

And museums such as the Ellis Island Museum of Immigration, the Tenement Museum, the Arab American National Museum tell stories about the immigrant experience and explore our nation’s long history of discrimination against immigrants and racist ideas of who can become “American.”

USCIS even has a web page recognizing museums’ important role in immigration and citizenship.

This past week, as part of the national outcry about the heinous treatment of children on the border, several museums offered statements sharing their outrage. Examples include the Boston Children’s Museum, Holocaust Museum Houston, and El Paso Holocaust Museum. In her statement, Judy Margles, AAM board member and director of the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education shares OJMCHE’s Oral History Project among other work the museum is doing on the topics of immigration. The Mexic-Arte Museum collected donations to assist immigrant families seeking asylum at its recent Family Day.

I am proud of the many Alliance members who, as a cornerstone of their communities, look for ways to help and give voice to the voiceless. I often say that the Alliance is about you, our hard-working members. A big part of AAM’s role is to champion your work and to facilitate the sharing of your best practices and ideas.

In the coming days, weeks, and months, the Alliance and our Latino Network will collect and share more resources and stories about the actions museums are taking to support immigrants and refugees. Please share your examples.

Lastly, if you too are furious at our government, please make a phone call or send an email to your Congressional representatives. Make a donation to one of the many organizations providing direct support. And please make sure you’re registered to vote in November.