This is one of the five trends from the 2019 TrendsWatch. Click here to read more about the full report.

“Colonialism and imperialism have not settled their debt to us once they have withdrawn their flag and their police force from our territories.” —Frantz Fanon

As we begin to build the 21st century, one of our most profound challenges, globally and locally, is grappling with the enduring effects of colonial practice. Decolonization is the long, slow, painful, and imperfect process of undoing some of the damage inflicted by colonial practices that remain deeply embedded in our culture, politics, and economies. Nations, organizations, and individuals are struggling with how to confront ongoing economic exploitation and dismantle the intellectual and social constructs that justified colonialism as the right and inevitable dominance of “superior” over “inferior” races. Museums, in their cultural roles of memory keeper, conscience, and healer, have an obligation to provoke reflection, rethinking, and rebalancing. Museums can help us deal with the dark side of history, not just emotionally and personally, but in a way that helps us build a just and equitable society despite our legacy of theft and violence.

Description of the Trend

Sometimes it seems as if colonization is the default condition of the human race, our history comprised of repeated episodes of one nation occupying the lands and exploiting the resources of another people. In the past 500 years, these waves have included the establishment of Belgian, British, Danish, Dutch, French, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, and Japanese empires through colonial expansion, building wealth through the extraction of resources, and in the process, suppressing and supplanting Indigenous culture and religions. In many continents (e.g., North America, Australia, and New Zealand), “settler colonialism” displaced Indigenous people from the land. Colonial power peaked just prior to World War I, with European nations controlling about 84 percent of the globe.

There are some signs that perhaps, at last, humanity is trying to break the cycle of colonial violence and redress its effects. Political colonialism began to unravel in the wake of World War II, as more than 80 former colonies gained political independence. More recently, we have begun the slow and painful work of internal decolonization. In the last decades of the 20th century, the US and Canada dismantled the government-sponsored residential school systems that separated hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children from their families and tried to destroy their language and cultural identity. In some countries, truth and reconciliation commissions have been tasked with uncovering and confronting government wrongdoing to create honest narratives of the past, lay the groundwork for healing deep intergenerational trauma, and advocate for reparative justice.

But confronting historic wrongs is not enough when many nations are still imposing internal colonialism on Indigenous people in settled lands. Exploitation colonialism is still at work as corporations and governments extract resources from Native lands and exploit Native lifeways. Nations populated by settler colonialism struggle with how to build a society that includes justice for Indigenous people. What is the next stage in our evolution? How will society resolve fundamentally conflicting values: wealth, development, and growth versus cultural sovereignty?

What This Means for Society

Organizations of all types are being asked to reassess their legacy and redress enduring damage. One of the most pernicious effects of colonialism is the cultural assumption of superiority, the recasting of the occupied “other” as exotic and inferior. Decolonization must perforce work to dismantle racism and white superiority. For this reason, it was particularly powerful when, in 2018, Susan Goldberg, the first female editor-in-chief of National Geographic, commissioned an independent assessment of the magazine’s treatment of race, and acknowledged its role in reflecting and reinforcing a colonial narrative of white superiority.

Now Indigenous activists and allies are pressuring government and industry to end the extractive practices that threaten native sovereignty, lifeways, and values. In 2016, members of the Standing Rock Sioux were joined by allies from around the world to protest plans for the Dakota Access Pipeline. The pipeline, designed to carry oil underneath the Missouri River, threatened regional water sources and historic burial grounds. While the protests were ultimately unsuccessful, they garnered international attention and created a model for building broad coalitions of public support for environmental action. In addition to raising objections to specific projects, such actions collectively challenge the cultural values and political and economic systems that prioritize short-term financial profits over concerns about climate change, oil spills, species extinction, and Indigenous rights.

There are numerous examples of how nations, organizations, communities, and individuals are working to acknowledge and redress the effects of colonialism. However, given how deeply this legacy is embedded in our culture, our power structure, and even our mindset, we have to ask if decolonization is even possible. We can’t undo history. But we can try to recognize and remediate the harmful legacy of colonialism, and mitigate the power of that legacy to do further damage. Acknowledging that decolonization can never be fully accomplished, we can commit to an ongoing process of changing our attitudes, laws, organizations, and behavior.

What This Means for Museums

Museums are intrinsically colonial, fundamentally reflecting a Eurocentric view of the world. Many were born directly from colonial practices, serving as trophy rooms of conquest and superiority. The field was shaped by scientific disciplines that validated racist worldviews, explicitly ranked the world’s cultures, and placed Europeans on top. Colonialism is embedded in the collections—in what museums chose to collect, how it was acquired, how it was documented—and in our methods of classification, display, and education. Museums are complicit in colonizers’ continuing control over how the world sees Indigenous people, and what Indigenous people know of themselves and their culture. The extent to which a specific museum is faced with obligations related to the legacy of colonization will depend on its location, its community, its collection, and its particular history of founding and funding. But all museums share a responsibility to help their country and their society address the legacy of damage.

The power, authority, and trust granted to museums by the public means that the sector has a commensurate responsibility not to preserve and perpetuate the destructive attitudes and practices of past times. As Puawai Cairns writes, museums may never be decolonized because “systemic resistance is too great, the colonial bones go too deep, and decolonizing requires much more sacrifice from colonial subjects than ever before.” That is true, but it doesn’t mean museums aren’t obligated to try.

One important facet of decolonization is the return of the tangible heritage removed by colonial occupiers. Honoring the claims of Indigenous people for the return of cultural artifacts will require shifts in both legal and ethical standards governing museums. In the US, the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act is a starting point for confronting colonial legacy, but the issues go far beyond the categories of collections legally subject to repatriation and the tribes legally recognized by the federal government. In 2016, the Australian parliament called for the British Museum to repatriate a Gweagal shield, but an act of the UK parliament prevents the museum from transferring ownership. (They offered to loan the shield to the Museum of Australia, but descendants of the shield’s original owner were not satisfied with that solution.)

Some museums maintain that they should not be expected to return contested artifacts even when they are legally able to do so, arguing that they steward their collections for all people of the world. However, this concept of a universal, or encyclopedic, the museum is being challenged by a growing number of national governments and Indigenous people who reject the premise that such “museums of the world” are exempt from claims for repatriation. The “Declaration on the Importance and Value of Universal Museums” released by 18 major art museums in 2002 maintains that museums “serve…the people of every nation.” In the intervening years, it has become clear that these people may insist that this service include ceding control over cultural heritage displaced by colonial practices.

Even when there is government support and consensus for decolonizing collections, there remain thorny questions of implementation, such as identifying who will pay for the process and who will receive the returned materials. A recent report commissioned by France’s President Macron recommends that objects taken without consent from sub-Saharan African during France’s colonial era should be permanently returned. The criteria for restitution outlined in the report specify that the claimant countries must have infrastructure “ready and prepared” to receive such collections. Senegal recently opened the Museum of Black Civilizations in Dakar to house returning collections. The construction of that museum, delayed for decades, was financed by the Chinese government as part of building economic relations with African nations. This example is exceptional, as most African nations don’t have access to the funds needed to house and maintain collections. What are the obligations of former colonial powers, or the museums that represent them, to help create that infrastructure?

Even as we address historical resource colonialism, we need new ways to address new issues. Contemporary biological collecting, particularly botanical collecting, with its potential for pharmaceutical discovery, can be seen as a form of scientific exploitation. The 2014 Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization to the Convention on Biological Diversity creates a framework for sharing the benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources in a fair and equitable way. (The US is not a signatory to this international agreement.) Some have criticized new projects to make high-quality 3D scans of the world’s cultural sites as “digital colonialism.” Technologists may see the scans as a way of saving and sharing world culture, but are these efforts enough? Who owns the copyright to the digital data, and who controls its distribution?

In addition, museums that focus decolonization initiatives only on their collections can overlook deeper issues of power, authority, distribution of resources, and access to opportunity. Decolonizing the museum, to the extent it is possible, should extend to examining how museum governance and operations may perpetuate colonial attitudes and power structures. How are Indigenous people given authority and voice in museums that serve their communities, preserve their heritage, and influence how society sees their culture?

Finally, there is a danger that the effort to decolonize will exploit people of color yet again, using them as natural resources to do the hard work without actually turning over power. Decolonization initiatives can create an illusion that the museum is “dealing with its past” when in fact there is no lasting change. Activist Harsha Walia writes, “‘I am waiting to be told exactly what to do’ should not be an excuse for inaction, and seeking guidance must be weighed against the possibility of further burdening Indigenous people with questions.” She further suggests that the “appropriate line between being too interventionist and being paralyzed” hinges on whether an institution is motivated by a sense of responsibility or of guilt.

Museums Might Want to…

- Cultivate awareness among staff, leadership, and boards around decolonizing museum practice. This might involve creating a team/committee/working group at the board or staff level. In any response, museums can ensure that representatives of Indigenous communities have significant power in shaping the process.

- Consider power structures in the museum. Discuss who holds power and how it is exercised. Who are the gatekeepers and how can they open the gates? How does philanthropy consolidate power on boards? Decolonization requires systemic reform at all levels of the organization: governance, leadership, staffing, and operations. Museums can start by developing new ways for accessing power that are inclusive and equitable.

- Ensure that diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion (DEAI) practices work in concert with, rather than as a substitute for, decolonization. How are Indigenous staff given authority and voice in their organizations? Decolonization will fall flat if the organization is not working inclusively and recognizing systemic racism in its own practice.

- Support Indigenous communities in their decolonization efforts by challenging stereotypical representations and uplifting Indigenous voice and perspectives. Cede authority, giving Indigenous communities space and power to tell their own stories and to use the museum’s resources (collections, space, expertise, reputation, connections) in service of their own needs.

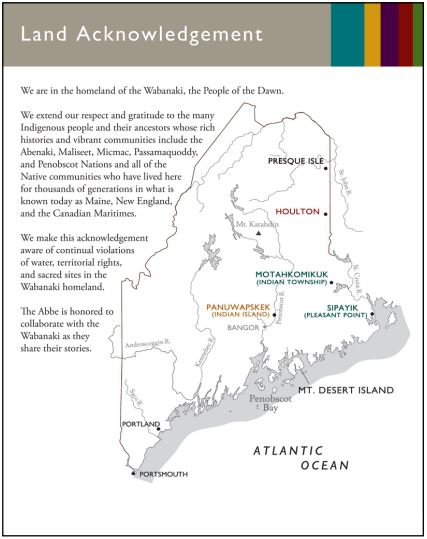

- Ensure that Indigenous communities and the legacy of colonialism are kept alive in public consciousness. As one simple but powerful step, open public events and gatherings with acknowledgement of the traditional Native (Indigenous/Aboriginal) inhabitants of the land on which the gathering takes place.

- Listen to criticism and be willing to change. Engage in constructive dialogue with activists who question the museum’s authority and traditions. Create policies and procedures for responding to protesters respectfully, and ensure that all staff are trained and supported in implementing these practices.

- Acknowledge that museums have been the beneficiaries of power structures that derived their wealth from the expropriation of Indigenous resources. Structural inequalities embedded in our current economies, including commerce, government funding, and philanthropy, reinforce that privilege. Individual museums can choose to play an active role in sharing and redistributing resources.

- Take the lead in truth-telling, even absent national action for truth and reconciliation, by prioritizing underrepresented history, art, and culture, and including marginalized and absent voices. As repositories of power, museums can give Indigenous people a platform to advocate for cultural, economic, and political decolonization. As trusted public institutions, museums can instigate and inform change.

- The starting point for this investigation within an institution will vary based on the museum’s goals, missions, and community stakeholders. Looking for that starting point is the first step in a long and difficult process that will never be complete.

Museum Examples

- The Abbe Museum in Bar Harbor, Maine, was the first nontribal museum to create an organizational mandate to develop and implement decolonizing practices. This initiative is supported by policy and a strategic plan and enacted by numerous Wabanaki people. The museum’s board is now majority Indigenous in addition to a Native Advisory Council appointed by tribal leadership across Maine.

- The Winnipeg Art Gallery created the Indigenous Advisory Circle, whose 24 representatives have significant input on exhibitions, curation, staffing, training, as well as the design of a new Inuit art center. One goal is to increase the number of Indigenous curators and administrators in the art world.

- When the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff renovated their Native American exhibition, curators partnered with 42 members of Colorado Plateau tribes. The tribal representatives determined the themes and the educational content of the exhibition. The first question the museum asked each tribe was, “Do you want to be represented in the gallery?” Deeper into the process, the representatives determined which items from the collection should and should not be used for the display.

- In 2017, the San Diego Museum of Man in Balboa Park established the position of director of decolonizing initiatives. Efforts to decolonize the museum’s practice centered on three main tenets: acknowledging the harm that the institution has previously perpetuated via colonizing practices; amplifying voices from within cultural communities that have been ignored in the past; and working in collaboration with such communities.

- In 2018, the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg, Germany, presented “Mobile Worlds,” challenging the traditional Eurocentric order of Western museums. In its review, the New York Times said, “‘Mobile

Worlds’ delivers on its contention that European museums need to do much more than just restitute plundered objects in their collections, important as that is. A 21st-century universal museum has to unsettle the very labels that the age of imperialism bequeathed to us.”

Further Reading:

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, adopted by the General Assembly in September 2007, at the 107th plenary meeting. The statement was described by the UN as setting “an important standard for the treatment of Indigenous peoples that will undoubtedly be a significant tool towards eliminating human rights violations against the planet’s 370 million Indigenous people, and assisting them in combating discrimination and marginalization.”

Honor Native Land: A Guide and Call to Acknowledgement, U.S. Department of Arts and Culture (2017). Created in partnership with Native allies and organizations, the guide offers context about the practice of acknowledgment, gives step-by-step instructions for how to begin wherever you are, and provides tips for moving beyond acknowledgment into action. Free PDF download.

The October 2017 issue of Art in America included an article titled “Shared Authority,” in which five specialists discussed practices and policies for decolonizing museums. A copy of the article is available from http://bit.ly/2UyWg9C.

Amy Lonetree (Ho-Chunk), Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press (2012). In this volume, Lonetree investigates how museums can honor an Indigenous worldview and way of knowing, challenge stereotypical representations, and speak the hard truths of colonization within exhibition spaces to address the persistent legacies

of historical unresolved grief in Native communities.