In this series of posts, EdCom’s Trends Committee is taking a deeper look at emerging phenomena identified in the most recent edition of TrendsWatch from the Center for the Future of Museums. In this post, they explore how the push for decolonization is making a concrete impact at two museums: Historic Fort Snelling and the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia.

Decolonization is defined in AAM’s TrendsWatch 2019 as “the long, slow, painful, and imperfect process of undoing some of the damage inflicted by colonial practices that remain deeply embedded in our culture, politics, and economies.”

As more and more institutions begin this process, it helps to look at examples already taking place in the museum field, and to explore the questions they raise. In this post, we look at two examples of decolonization in the field, from the Minnesota Historical Society and the University of Virginia.

The two museums are different institutions at different points in their decolonization journeys, but one thing they have in common is the practice of land acknowledgment. Land acknowledgments take different forms but are often a short statement in testament to the indigenous communities that either traditionally or currently have ties to the site of the museum, site, or program. On December 16 at 3 p.m. EST, EdCom will host an EdComversation webinar on this topic with presenters from the two institutions whose case studies are explored below.

Case Study: Fort Snelling

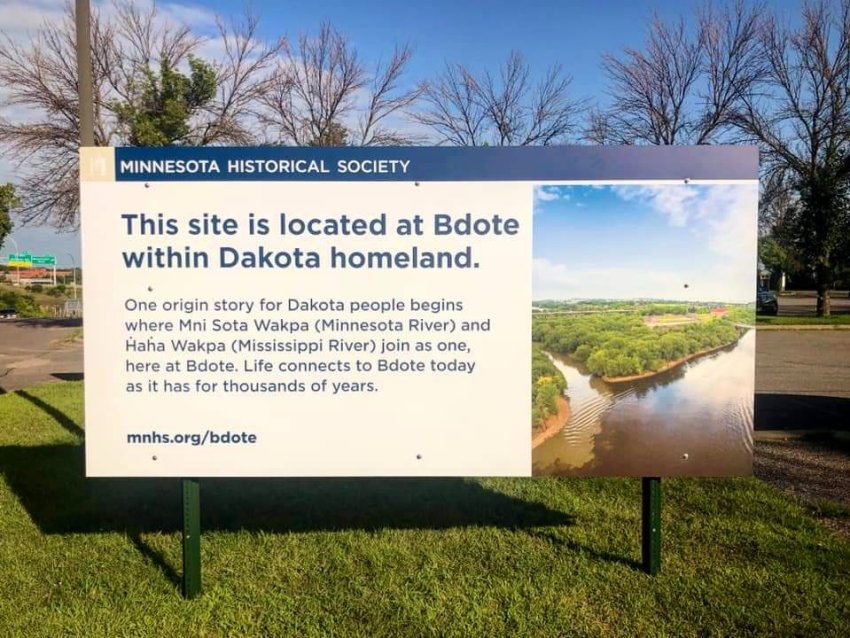

For years now, the Minnesota Historical Society (MNHS) has been working to broaden the historical narratives shared at all of its historic sites, including at Historic Fort Snelling. This National Historic Landmark sits on Dakota homeland at Bdote, the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers, with a history spanning ten thousand years. The site’s programming has been expanding over the last several years to better interpret its long and rich history, which includes stories of soldiers, veterans, and their families from the nineteenth century through World War II; enslaved and free African Americans; Japanese Americans during World War II; and Native American groups who have lived in the area for centuries.

Currently, Historic Fort Snelling is in the midst of a large construction project that aims to revitalize the site. Plans include removing the current visitor center and creating a new one within a rehabilitated 1904 barracks, as well as updating the landscape to make better use of its twenty-three-acre property. By including outdoor learning spaces, creating visible connections to the rivers, and improving wayfinding, the site hopes to greatly improve the visitor experience.

Given the intensiveness of this revitalization, the MNHS is exploring whether they should consider a name change to reflect the new visitor experience that will be available starting in 2022. While the name of the 1820s fort itself, Fort Snelling, will not change, there is some discussion around what the entire campus, currently named Historic Fort Snelling, should be called. Many names have been discussed, including some that would reflect the Dakota name for the place, Bdote.

To explore the possibility of a new name, the MNHS began informing and collecting input from the public, through a website and survey as well as six in-person meetings around the state of Minnesota. The public input process was closed in mid-November, and staff is currently working with MNHS Board members to analyze the public input and other data. In addition to this feedback from the public, the MNHS will use its mission, vision, values, strategic priorities, recent visitor experience data, and input from key stakeholders to inform its decision. A report summarizing the data will be presented, and the board will then make a recommendation—either that the name should change, or that it should remain the same: Historic Fort Snelling. If a name change is recommended, it will then be submitted to the state legislature for approval.

The work being done at the MNHS and Historic Fort Snelling is a large-scale example of what it might look like to take on the work of decolonizing a museum—at least in name. This process has not come without its difficulties, as one can imagine the amount of work and coordination that has gone into such a state-wide effort. But it is clear that the MNHS is prioritizing data and key conversations as it works to form a decision on the subject.

What are your institution’s priorities when it comes to decolonization? Perhaps this is a good question to start with. Is it expanding the objects you have on view to reflect more diversity? Is it reinterpreting your collection to tell stories that have previously gone untold? Is it making conscious efforts to evolve workplace culture away from being predominantly white, male, etc.?

Alternatively, for institutions that are further along in their decolonization journey, the question might be, “What are the next steps?” Another case study will help us explore that. At the University of Virginia, we see an example of what the decolonization process looks like in full, systemic scale at a small museum.

Case Study: Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia

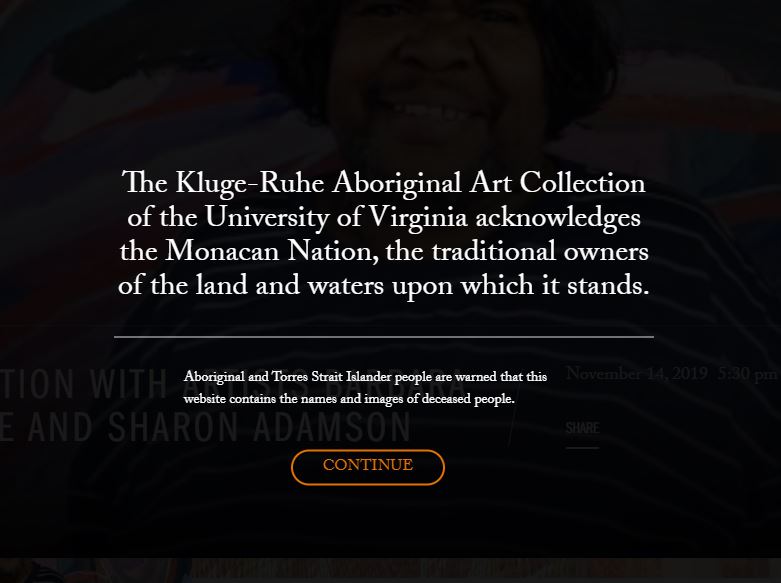

The only museum of its kind outside of Australia, the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection has Indigenous representation, voice, and recognition embedded in its mission and values. This manifests in a variety of ways through its programming, curation strategies, publication, management, and more. Below are a few of our favorite examples that their staff shared with us, centered around two of the suggested actions from the TrendsWatch article:

Take the lead in truth-telling:

- “Our institutional language addresses the Aboriginal perspective of the past.” In tours, wall text, and online, the museum uses the term “invasion” rather than “colonization.”

- “We have an entire permanent exhibition devoted to unveiling whitewashed histories and highlighting Indigenous resilience in the face of invasion.”

- “We have raised awareness about the lack of diversity in the museum profession, and have undertaken initiatives to train emerging museum professionals from underrepresented backgrounds in a comprehensive curatorial and internship program funded by the Mellon Foundation.”

- The Kluge-Ruhe Collection also practices land acknowledgement in a number of ways, and uses their website as a platform to educate others about best practices for doing so.

Consider power structures in the museum:

- “Henry [Skerritt], our curator, is tremendous at opening his ‘curation gate’ to Indigenous Australians. For example, he is working on a major travelling exhibition called Madayin, in which Yolngu people are curating, writing, and making all major decisions about how their culture, art practice, and histories are framed and communicated to the public. Artists and communities are advised on the curation of every exhibition, and are frequently Aboriginal-community curated.”

- “When it comes to writing about the work on view, we seek Indigenous authors to write essays for exhibition catalogs whenever possible, whether they are Indigenous Australian or First Nations people from other countries. When we are developing web resources that will have extensive reach, we co-write these resources with Indigenous Australian knowledge holders.”

- “In collections, we seek to observe a variety of cultural protocols with sensitive objects, we use Indigenous place names and terminology in the database and exhibition spaces (English is always parenthetical), and we provide time and space for visiting Indigenous knowledge holders to have complete access to objects and records from their communities.”

It is important to remember that decolonization is a never-ending process. While the Kluge-Ruhe Collection has the advantage of being specifically mission-driven to represent Indigenous art and stories, all of these examples can be applied to other kinds of institutions.

In selecting your institution’s next steps, it may be helpful to develop both a short-term plan and a long-term vision for decolonization. How can your museum welcome and represent Indigenous perspectives now? What more can you do in five years? Ten? One easy place to start is by assessing the Indigenous stories that are represented in your collections, exhibitions, and programs, and considering those that are missing. Then reach out to those Indigenous communities and ask them for help in filling the gaps. This resource from the Museums Association of Saskatchewan offers some useful tips on the best ways to engage in conversation with Indigenous communities.

POLL: Does your institution participate in land acknowledgment? Fill out the form below!

This post was presented by the EdCom Trends Committee. Special thanks to: Nicole Wade, Collections Manager and Registrar, and Lauren Maupin, Education and Program Manager at the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia, as well as Kevin Maijala, Interim Deputy Director of Learning Initiatives with the Minnesota Historical Society.