I’m often asked which topics featured in CFM’s TrendsWatch report proved to be of enduring importance, and which fizzle. I’m happy to say that so far, all the trends we’ve identified have continued to be significant for our field. Case in point, crowdsourcing—a topic CFM examined in our very first forecasting report, TrendsWatch 2012. Today on the Blog, Jaan Elias, Director of Case Research at the Yale School of Management, shares a particularly interesting example of harnessing the wisdom of a very particular crowd.

–Elizabeth Merritt, VP Strategic Foresight and Founding Director, Center for the Future of Museums

Museums have employed crowdsourcing, the practice of enlisting the help of the public to identify objects, contextualize artifacts, and discover complementary material. However, most museum crowdsourcing to date has involved the creation of exhibits. Could museums turn to crowdsourcing to help formulate organizational strategy? Inadvertently, we were able to partner with Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History to hold an event that showed how this might be accomplished.

I say “inadvertently” because we hadn’t intended to create a crowdsourcing vehicle. Our job at the Yale School of Management (SOM) Case Research and Development Team is to document difficult management situations to serve as classroom exercises for students. When our neighbors across the street, the Peabody Museum, approached us about describing their strategic dilemmas around a planned renovation that would close the museum for at least two years, we readily agreed. The case study fit with our curriculum—SOM offers a number of courses in social enterprise management, and SOM alums play an important role in the museum world, e.g., Gail Harrity (president and COO of the Philadelphia Museum of Art ), Daniel Weiss (president and CEO of the Metropolitan Museum of Art), and Thomas Krens (former director and senior advisor for international affairs at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation).

We decided to debut the case not in a classroom, but as the subject of the Greater Yale Case Competition, an event designed to bring together teams of Yale graduate and undergraduate students to test their analytic and creative abilities. Held on February 10, 2018, the contest gave the student teams about twenty-four hours to formulate a strategy for the Peabody, based on our case study. Then the teams came together at the management school to present their plans to judging panels made up of Peabody personnel and university faculty.

Ninety students on some twenty teams presented a wide variety of ideas. Elements that appeared in a number of their proposals resonated with museum staff:

- Building apps to gamify visiting the museum to encourage repeat visits and enhance the museum experience without substantially altering signage or displays.

Teams proposed a number of ways to utilize mobile technology. One team argued for creating a mystery story that can only be solved by finding clues among the museum’s exhibits. Another suggested that ads for the museum around New Haven be synched with videos of exhibits delivered to smart phones. Another group proposed giving visitors headphones, not for a guided tour of the museum, but to present aural landscapes of the dioramas and exhibits. - Dedicating a portion of the renovated building to serve as a gathering place for Yale students and reserving a gallery for exhibitions curated by Yale students.

Teams highlighted the need for a “third space,” something that was not their dorm room or the library, especially in the area of campus where the Peabody is located. This would entail opening some of the Peabody’s space after hours, but would help foster student interest in the museum. Students emphasized that the space need not be a café nor elaborately decorated. - Buying a bus or trailer to house traveling exhibitions for New Haven schoolchildren during the museum’s hiatus.

The Peabody is much beloved by New Haven’s schoolchildren, and teams feared that a hiatus would mean that there would be an entire age group of children who would not experience the museum. Outfitting a bus or trailer to bring the museum to K-12 schools with either real objects from the museum’s collections or digitized representations would help keep interest alive. - Eliminating the admissions charge and making up the shortfall with increased revenue from a café or the gift shop.

Many planners hoped to eliminate entry fees as other Yale museums have done, to make the museum more accessible to the greater community. Eliminating fees would bring in a wider audience, but would remove a significant source of revenues. The museum had looked at the impact at comparable museums of eliminating visitor fees. If entry fees were eliminated, visitor traffic was expected to increase from 150 thousand visitors per year to around 250 thousand. If paid admission fees continued, visitor traffic was expected to increase to 170 thousand. (For context, admissions fees currently bring in about 4 percent of the museum’s $16M annual revenues, while museum store sales bring in a little over $.5M, or 3 percent of revenues.)

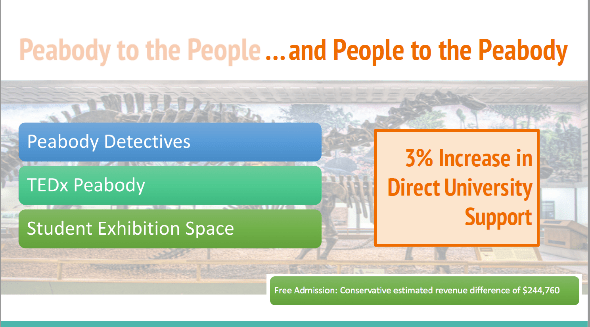

The winning proposal outlined a multi-pronged approach to how the museum could connect with children and families, community adults, and the Yale Community. This team’s strategy included:

- Peabody on Wheels—a bus with Peabody exhibits to visit schools, community festivals, and other target sites

- Peabody on the Go—mobile apps for children and adults that explore fossils, support museum trivia nights and publicize museum events

- Peabody Detectives—a mystery-based escape room in the museum

- TEDx Peabody—a series of talks on museum-related topics

- Student Exhibition Space—providing a “third space” café as well as hosting student-curated exhibitions.

While it remains to be seen which if any of these proposals will be adopted, student teams aided museum planning by fitting their ideas into the Peabody’s strategic context, complete with financial projections, marketing plans, and mission-based justifications. Overall, the Peabody staff I talked to were inspired by the student work.

It is understandable that museum managers may feel somewhat uncertain about having a “crowd” analyze operations and suggest strategy. However, as this Harvard Business Review article notes, “crowds are moving into the mainstream,” and they can be an important resource for formulating innovative solutions, even for deep strategic questions. McKinsey has touted “participatory modes of strategy development.” The consulting firm cites two major benefits to crowdsourcing. First, it improves the quality of strategy by “pulling in diverse and detailed frontline perspectives that are typically overlooked.” Secondly, crowdsourced strategy can build enthusiasm among stakeholders for a particular plan or view of the future.

Building on our experience, I can offer three suggestions to anyone looking to use crowdsourcing in strategy formulation:

- Choose the right crowd—We were fortunate to have a pool of bright, highly motivated students further inspired by cash prizes. Other museums might look to their members or staff to become the source of strategic ideas. We also required teams to include students from different schools, to ensure that each team had the experience of melding disparate views and skills. The diversity aided in creating superior presentations. For example, the winning team consisted of a SOM student, a law student, a medical school student, and a graduate student in history.

- Offer as much information as possible—Our contest centered on a “raw” case study, an online compendium that brought together photos, text, reports, spreadsheets, and videos. The raw case allowed students to explore various options in depth.* A well-prepared case study can have further utility as well. For example, our case helped inform a class about designing innovations for the Peabody.

- Stage a good event—While an increasing number of encounters are virtual, we found bringing teams together in a single place to present their findings not only built excitement but also allowed for feedback that could improve proposals. For example, the winning team at our event took feedback and improved their ideas for a subsequent presentation before the full Peabody staff.

*Readers of this blog who would like to read our case study on the Yale Peabody Museum should visit this link and enter “MUSEUM” in the discount code box. Case access will be free until June 15, 2019. An excerpt from the case is available online for free, as well.