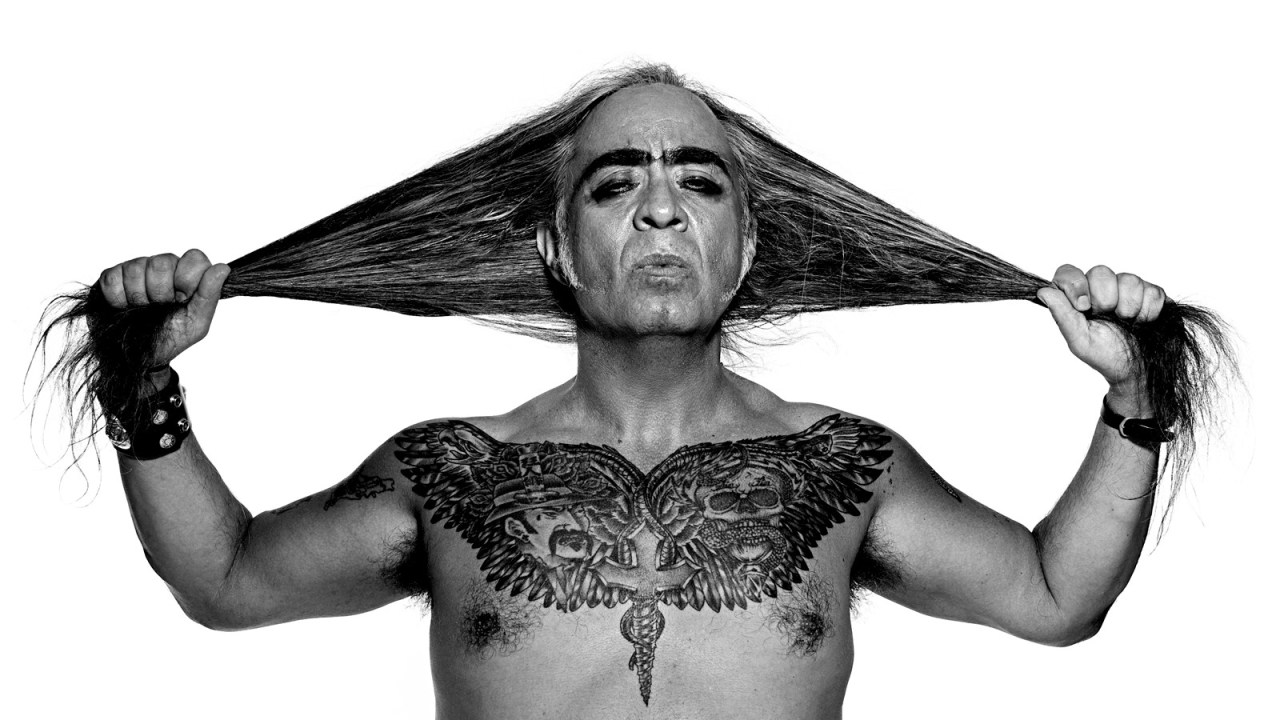

Yes, even performance artists grow old! Here is an insightful look into the heart of one of America’s most dynamic contemporary artists, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, as he hits the ripe old age of sixty-three! (Note: I happen to have the privilege of knowing “GGP” through my own daughter, who is Manager of La Pocha Nostra, his performance troupe).

–Bill Tramposch, 2019 Aroha Fellow for Museums and Creative Aging

I just turned sixty, which is quite dramatic if you consider that I am a “radical” performance artist who is well known for his transgressive aesthetics, political bravado, and uncompromising irreverence. I am the Vato who became notorious for speaking in border tongues (Spanglish glossolalia) and spending three-day periods inside a gilded cage as an “undiscovered Amerindian;” the very Vato who crucified himself dressed as a mariachi to protest immigration policy. The loco who practices political acupuncture and psychomagic acts against violence. Suddenly, I’m growing white hair, a potbelly, and a double chin. And my voice sounds reasonable and tempered by my experiences. A cruel curator friend of mine tells me that “[I am] no longer feared or desired but respected.”

Ouch!! When young rebel artists call me “professor Gómez” or “maestro,” it pinche flips me out. And when the head waiter at a restaurant tells me, “Sir, your daughter (my thirty-year-old gorgeous wife) is waiting for you at the back table, my heart quietly bleeds. America is no country for old men, and I am not your typical “man.” I am queer and my best friends and collaborators are all feminist women and queers.

But let me elaborate a bit: I have spent a lifetime utilizing my body and my tongue as tools to express my opposition to mainstream culture and values, advocating anti-authoritarian artistic practices and supporting outsider communities. And I always thought of myself as age-less, or rather as permanently young. In fact, those who know me see me as a permanent “adolescent” in my humor and syncopated energy. Is this a critique or a compliment? I don’t really know.

To remain young, for me, implied a relentless capability to reinvent myself, to constantly take unnecessary and sometimes stupid risks, and to remain in touch with the cultural and political pulse of the times and the streets. It also meant not to think too much about the past or the future (I am lucky to have a strategic selective memory that edits out all traumatic experiences I’ve had); to always operate in the “here” and the “now,” the time and place of performance art. My existential motto was/still is, “If I don’t go loco at least once a week, I will really lose my mind,” and I’ve been loyal to it for at least thirty-five years.

By the time I turned fifty, my rebel contemporaries and partners in crime began to settle down. They got full-time jobs in academia and the art world. They were married and began to have children. They bought expensive homes and SUVs. And suddenly they had much less time to hang out in seedy bars and undertake daring art projects. I saw them, one by one, losing their spunk and bravado, becoming cautious and moderate, talking about “saving for the future” (an anathema for a radical artist) and dyeing their hair to hide the grey. But stubborn myself, I kept my long hair in a ponytail as a warrior talisman and began to use eyeliner and makeup every day as war paint. My son, Guillermo Emiliano, was horrified!

My contemporaries gave me all kinds of unwanted advice: “Gómez-Peña, you should write more accessible (and profitable) books, you know, like Richard Rodriguez or Sandra Cisneros; follow the example of Eric Begosian and Ana Devere-Smith and get a job in Hollywood or in a TV series or at least get a tenured job in academia. You can be dean of performance studies in some fancy university. It gives you medical insurance, the certainty of a monthly check, and lots of free sabbatical time to lounge in any country of your choice.”

Those kinds of comments made me depressed. The subtext was “aren’t you a bit old to live as a permanent outsider artist?” I hung out more and more with younger artists who were willing to jump into the abyss with me. I even perceived a generational fault line between people of my age and me. It was…weird! (My compadre, Gustavo, and I are still often the only vatos over sixty hanging out in a bar full of artivists and local eccentrics.)

But back to my story: I experienced my mid-life crisis by going out with someone seventeen years younger than me, a Mexico City upper-class princess (TRN). Our generational differences in “lifestyle,” taste in art, and political beliefs made me even more conscious of my age. One day, I realized I was definitely going through my climaterio (Spanish for male menopause) when I found myself disco dancing in a Mexico City nightclub surrounded by twenty-year-old hipsters. “Patético”—I thought. I excused myself, pretended to go to the restroom, and escaped through the back door for good. Now in retrospect, I realize that this strategic escape was a spiritual relief and that I wouldn’t give anything to be that age again. My grandma (RIP) told me: “Sometimes, you just have to walk away to remain dignified.” She was right.

In my mid to late fifties, I began to perceive the symptoms of aging as cruel. I wrote in my performance diary:

“When I was younger I had an amazing encyclopedic memory; now I just have dozens of herbal supplements from China. When I was younger, I had visions, utopian visions; now, I have dreams, impossible dreams. As a young performance artist, the streets were my laboratories of experimentation; as a ‘mature’ artist, conversations and rehearsals have replaced the streets. Taking physical, aesthetic, or political risks was an integral part of my artwork. Today, I am more interested in the pedagogical dimension of my art. I have even stopped getting naked on stage…I used to engage in 3-day-long parties with the old Pocha Nostra members (Sifuentes, Violeta Luna, and Juan Ybarra). Now, I still go crazy twice a week with Balitronica and Saula, but I pay for the consequences: I now have arthritis, a fatty liver, asthma, and mysterious neurological disorders. I used to always collaborate; suddenly I am thinking more and more of my solo work, and of my personal voice. (Was I becoming more selfish or merely wiser?)…It gets worse: I am now becoming increasingly more conscious of my ‘artistic legacy,’ another anathema for a performance artist. But worse than anything, I am becoming more tolerant of political difference and cultural insensitivity…that is with the exception of Trump and the alt-right: I no longer have formidable intellectual fights with conservative critics and ethnocentric curators. Instead, I write open letters to the arts community, organize town meetings and/or challenge my adversaries in conversations in dive bars enhanced by scotch. I no longer know how to lie or be diplomatic, which causes all kinds of trouble with my neighbors, landlord, and local racist cops. Even Balitronica gets ruffled by my boldness. And she holds two black belts.”

In my late fifties, I also became increasingly aware of the fragility of my body. After a lifetime of abusing my body partying constantly in altered states of consciousness and simply working very hard,…one day I got gravely sick. While touring Brazil, I caught a tropical parasite with an unpronounceable Latin name and experienced a total liver crash. With my body connected to machines at a Mexico City hospital, I came face to face with Death (for the third time). I looked like one of my Chicano cyborg performance personas. For eight months I faced the prospect of a life without touring, without performing, life as a stationary intellectual forever facing my inner demons in front of my laptop. I was inconsolable.

During my slow recovery I wrote my first script ever that dealt with my past: a biographical reflection on what it meant to be a Latino artist facing the abyss of the end of the century and the dark clouds of middle age. I noticed that my poetic tone had changed. I was more somber, and self-critical; less outrageous. I was thinking about my place in the world, my relationship to family, friends, art, community and the universe at large. I had lost some of my sense of humor. I was obsessed with literary craft. That script was better literature, but denser and clearly less accessible to a live audience. I only performed it for six months. It still remains unpublished.

I eventually recuperated from my illness and went back on the road, thinking it all had been a temporary nightmare. But I was wrong, so pinche wrong! Soon my memory began to betray me. I started forgetting names, conversations, incidents, and book and film titles. My recent memory, say of the past three to five years, is even worse. I first attributed this loss to Caribbean rum and parasites from touring Haiti, tobacco, and sleeplessness, but then I started talking to other artists my age, and they were all going through an identical experience. My native compadre James Luna (RIP) told me: “Don’t worry ese; it’s the ‘Big Smoke.’ You are simply going through the Big Smoke. We are all going through the ‘Big Smoke.’” And my wise and hilarious mother (RIP) told me: “It’s the German guy inside of you, Mr. Alzheimer. You have to start making peace with him. He is going to be living inside of you for a long time. It’s like your evil twin. You won’t even remember my words.” It wasn’t funny.

I began to consciously engage in memory exercises, as acceptance exercises. I became an involuntary Chicano Buddhist, a disciple of Jodorowsky and Castañeda. I started using canes as “memory sticks,” writing enigmatic notes on my arms and making obsessive “to do” lists in my myriad diaries. I never told anyone what I was going through. It was my embarrassing secret. I only shared it at 2 am with my barfly friends and in the early morning with my wife, Balitronica.

And then, of course, there was the loneliness: Young people simply didn’t look at you anymore. I felt completely desexualized and defanged. Once I overheard a twenty-year-old pinche techie telling his friends at a café, “look at that weird and scary old Indian dude. He’s like, he’s like a Hollywood Indian dude.” I turned around and told them: “You ‘dudes’ suffer from educational deficiency. Were you raised by mothers or by computers?” “F— off old man!” they said. And I walked away. I remembered the words of grandma. But I was hurt.

I now wonder if as a sixty-three-year-old “rebel artist” one can remain current, “hip,” sexy and connected to the world, or if soon I should withdraw with dignity from the world, become a neighborhood drunk selling my poems from table to table in seedy bars, or commit ritual suicide as my last performance art piece. But when these thoughts begin to linger over my inner poetic stage, my sense of humor and my love for life somehow redeem me once again.

I think to myself: Perhaps I can hang my weapons on the wall and still be a warrior like my Colombian Brujo once told me or perhaps I can become a hip elder loco artist like the late Marcel Duchamp or Burroughs or, better yet, a sexy old rockero like Bowie or Jagger. Perhaps soon my wife Balitrónica will take me around the stage in a lowrider wheelchair during our Pocha Nostra performances (wait, we already did that at my Retrospective in Mexico) and I can direct the performance on-site like a broken Chicano Kantor…Perhaps this and that.

(…)

For the moment my only hope is to continue walking, not running, with style, lots of style; doing my morning “interpretative shamanic punk dance routine” to remain present, open-minded, and tolerant; to consciously continue taking risks and opposing authority whenever I smell it; and to exorcise any disconcerting thoughts about the future as much as I can. My blessing is that Balitronica, my wife, is gorgeous and bold and her ineffable energy and performative wildness inspire me every day. Despite our generational differences, she is as much of a lunatic as I am, and we both live by the laws of poetry and quantum physics…

–San Francisco

September 23, 2017

Post-script, 2019: I stand naked in front of a mirror for an extended period of time. It’s midnight in a dressing room. The performance is over and I’m drinking a delicious single malt scotch, toasting with my other selves on the other side of the mirror and making peace with my sixty-three-year-old aching body full of performance scars, fading memories, and biographical tattoos. I toast to my panza (tummy), my dimming memory and libido. This aging scotch tastes better than ever. My flying Chihuahua Alonso Pepito “Orlak” the First is barking at his own image on the mirror. Tomorrow I go on the road again. Saula, Balitronica, and I will perform the latest version of “Adam and Eve in times of War,” a ritual performance involving cow carcasses and nude bodies. I’m still a nomadic provocateur.

Life is ok. Salud!

About the author:

Guillermo Gómez-Peña is a performance artist, writer, activist, radical pedagogue, and director of the legendary performance troupe La Pocha Nostra. His performance work and twelve books have contributed to the debates on cultural & gender diversity, border culture, and US/Mexico relations. A MacArthur Fellow, Bessie and American Book Award winner, he is a regular contributor for newspapers and magazines in the US, Mexico, and Europe, a contributing editor to The Drama Review (NYU/MIT) and the Live Art Almanac (Live Art Development Agency-UK). Gómez-Peña is also a Senior Fellow in the Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics and a Patron for the London-based Live Art Development Agency. He received a 2019 Guggenheim Fellowship and is currently preparing two new books for Routledge and a documentary portrait of his beloved troupe.

A version of this text will appear in his upcoming Anthology.

Write on, essay! Bien dicho “maistro!” Great hearing yr thoughts on the screen, tlazos for sharing. Es tu bio-genetic cultural disposition, maistro, es ke tu prolly

eres Azteca y Chumash…. yu drink choo mash, get naked choo mash, go to protestas y cantinas choo mash, yr just CHOO-MASH! Nov 8 remember Tenochtitlan. Un abrazo fuerte, y saludos rebeldes y fraternales del Chicano Secret Service. 2019: Xican@ Time!

I don’t know, you look pretty sexy to me…

If anyone can pull off being both loco and wise at the same time, that’s you. And this text proves it.

Punk on.

Hi Guillermo, I am four years older than you and of similar lenght of performance art experience, we met in the past… and reading this text at first I started to laugh. But continuing more patiently… yes, I realized I agree with you in some points and sense. So – the timeline of each of us must to be individual, a bit different, but the general succession of events and direction is common. And I wanna say – it’s still a nice feeling to be on the road with the other human beings like you.

Hugs,

Artur Tajber

Pochanostranismiticamente puntual reflexion – me llevas 14 años, y ya el Señor Aleman tambien llego a mi vida, Salud Maistro!

Abrazos,

Eliu